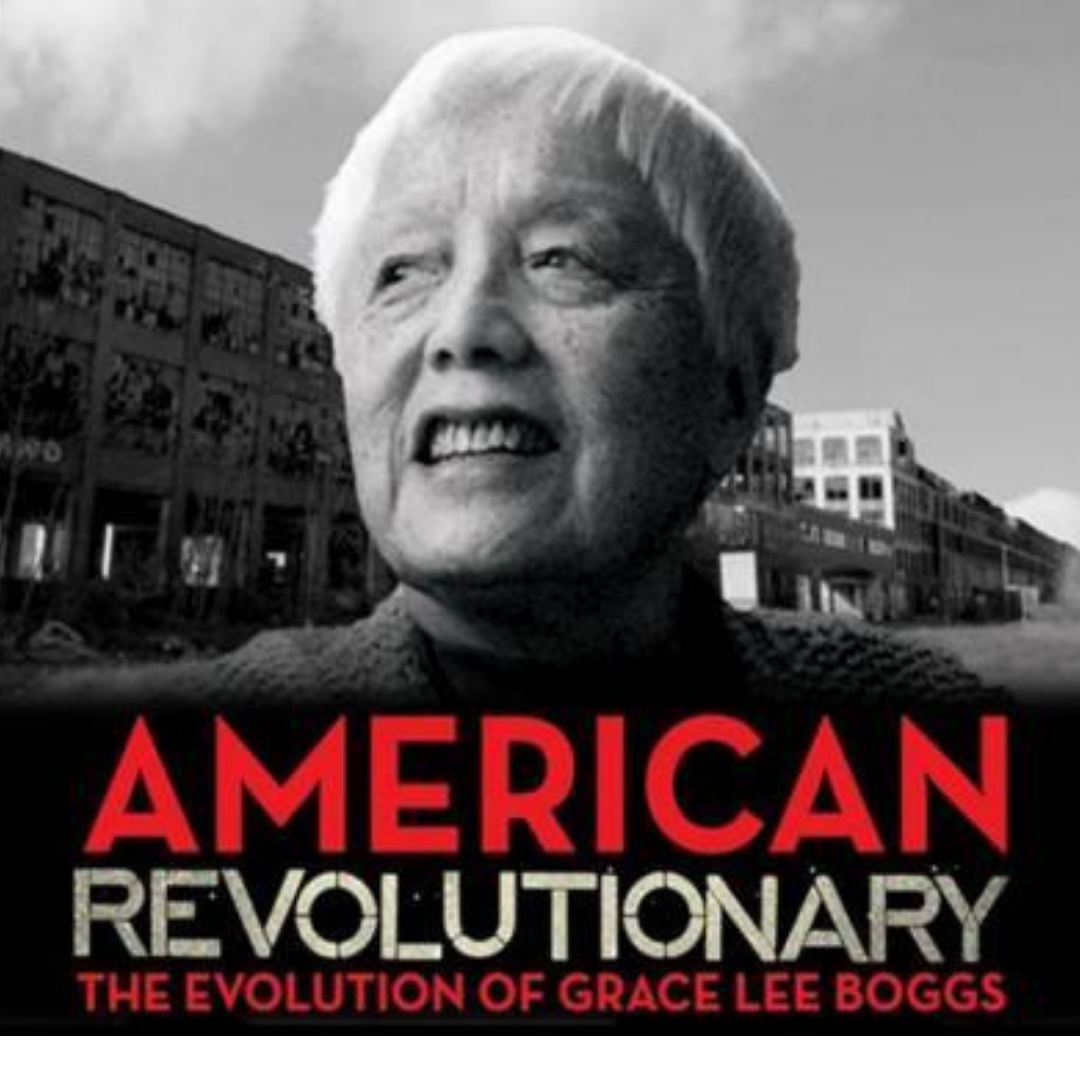

Self Evident Presents: “American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs” (by Making Contact)

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

This episode comes from our friends at Making Contact, a radio show that analyses critical issues and showcases grassroots solutions in order to inform and inspire audiences to take action.

Based on the documentary “American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs” by filmmaker Grace Lee, this episode takes a close look at Boggs’s lifetime of vital thinking and action — from labor to civil rights, to Black Power, feminism, the Asian American and environmental justice movements and beyond.

Revolution, Boggs says, is about something deeper within the human experience — the ability to transform oneself to transform the world.

Check out Making Contact at radioproject.org. or wherever you listen to podcasts!

Credits:

Special thanks to Grace Lee, the producer and director of “American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs.”

The Making Contact episode producer and host is Anita Johnson.

Music Credits: Bontex, Creeping Blue Dot Sessions, Grand Caravan Invincible + Waajeed, Detroit Summer Audio Banger, the Garden State Show

Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts Creator Program — and with the support of our listener community.

Transcript

INTRO

Cathy: Hi, it’s Cathy!

Cathy: This week, we’re sharing an episode from the show Making Contact. Making Contact is an award-winning public affairs program that works to broaden debate on critical social issues and help give voice to diverse perspectives.The episode that we’re featuring is called “American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs.” It’s actually based on a documentary of the same name, by a filmmaker Grace Lee. For those who don’t know, Grace Lee Boggs was an influential activist, writer and speaker, and she is often regarded as a key figure in Asian American activism. She lived until 100, and it’s incredible to hear her share much of her own personal story in this episode, in her own words.

Cathy: So we’re linking to Making Contact’s website in the show notes, please check them out wherever you listen to podcasts! And learn more about the show at radio project dot org.

Cathy: Ok, here’s “American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs.”

Anita Johnson: Anti-Asian violence has increased since the start of the pandemic last year. #StopAsianHate became a viral hashtag much like #BlackLivesMatter in the wake of Black people killed by police officers. The relationship between Black and Asian Americans is complicated. However, the groups are united in their efforts to call out white supremacy as the source of the violence against both groups. Solidarity between the Asian and Black community.

Take Grace Lee Boggs, an Asian-American woman who spent the better part of the last century in Detroit advocating for human rights for Black people. As we celebrate what would have been her hundredth and sixth birthday on June 27th, we look at her life as documented in the film, "American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs.".

Born in 1915 and Rhode Island, Boggs fought for social justice until she passed in 2015 at a hundred years old. Boggs describes her early organizing work in Chicago.

Grace Lee Boggs: And then I went out into the world, and I found that even department stores would say, "We don't hire Orientals." So I get on a train and went to Chicago, found a job there in the philosophy library for $10 a week.

It wasn't very much to live on. So I found a woman who said I can stay in her basement, rent free. The only trouble was that I had to face a barricade of breasts in order to get to the basement.

So one day, I came across a meeting of people, protesting rat-infested housing.

That brought me in contact with the Black community for the first time. And I want you to think about this now. I had never been in contact with Black people before. In 1941, the depression had ended for white workers but not for Black workers. I was aware that people were suffering, but it was more a statistical thing. And here in Chicago I was coming into contact with it as a human thing. Being in contact with the Black community, brought me in contact with the 1941 March on Washington movement to demand jobs for Blacks in defense. One. Tens of thousands of Blacks are ready to March on Washington and Roosevelt couldn't afford that to happen. So he issued an executive order 8802 to banning discrimination in defense plants. I found out that if you mobilize a mass action, you can change the world. And I thought to myself, boy if a movement can achieve that, that's what I want to do with my life.

Anita Johnson: In the early 1960s, Grace Lee Boggs moved away from the Marxist framework to focus on revolution.

She saw emerging right here in the U S from within the Black community. She began speaking out publicly in support of the Black power movement and quickly became a force to be reckoned with, networking with other civil rights activists across the nation, fighting against racist policies and gaining a reputation with the FBI.

Even Angela Davis, the 1960s Black power icon, described Grace Lee Boggs as quote, having made more contributions to the Black struggle than most Black people have. End quote. This speaks volumes about Grace Lee Boggs, the daughter of Chinese immigrants who went on to make a tremendous impact within the Black community.

Grace Lee Boggs: The Negro revolt is here. I believe that the Negro revolt represents the beginning of a new revolutionary epoch.

I made a speech at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara. I try to help these male intellectuals, liberal intellectuals understand that the Black movement was about something deeper than rights.

Archival Recording: One could say for the American Negro to achieve a middle-class white American standards is a revolution.

Grace Lee Boggs: I don't think whites understand the degree to which Negros do not want their whiteness.

I am trying to suggest that the Negro is striving to become equal to a particular image of himself, that he has achieved, that he is not trying to become equal to whites.

It was a great philosophic transition for me, which I had begun when I began examining the difference between Martin Luther King and Malcolm.

Malcolm X: The goal of Dr. Martin Luther king is to get Negros to forgive the people who have brutalized them for, uh, for 400 years by by lulling them to sleep and making them forgetting what those whites have done.

Martin Luther King Jr.: That was a great deal of difference between non-resistance to evil and non-violent resistance.

Grace Lee Boggs: My relationship to King has changed over the years. I was one of the organizers of the 1963 March down Woodward Avenue in Detroit.

Martin Luther King Jr.: I have a dream this afternoon, one day right here in Detroit, negroes would be able to buy a house anywhere, that their money will carry them.

Grace Lee Boggs: I didn't think... I really thought he was naive. I really did because I was a Malcolm person. I would go and hear Malcolm speak..

Malcolm X: You're the one that make it hard for yourself. The white man believes you when you go through them with that ole sweet talk. Cause you've been sweet talking him ever since he brought you here.

Grace Lee Boggs: And audiences would squirm as he would challenge them to think differently, to transform themselves.

We see the events of 1963 through the eyes of the mass media.

We see events like that, and they're not aware of the struggles that were taking place and forcing new developments. Martin Luther King was being persecuted by the FBI during that period as being pro communist. Many people in the Black movement were afraid that if they didn't purge themselves of left leaning elements that the movement would be destroyed.

Anita Johnson: Here's historian, Stephen Ward, discussing Grace and her husband Jimmy Boggs' perspective on radical and militant action as a strategy of the civil rights movement.

Stephen Ward: I think they felt that violence was already happening and that violence was inevitable.

In fact, it was at the grassroots leadership conference where Malcolm X delivered one of his most famous speeches message to the grassroots.

Grace Lee: Do you want to play the record?

Grace Lee Boggs: Would you like to play it?

Malcolm X: We want to have just an off the cuff check between you and me. Us. Concerning the difference between the Black revolution and the negro revolution.

Stephen Ward: Jimmy and Grace, they've been thinking about revolution for a decade and a half. So now they're seeing in this particular radical or militant stream of Black protest, a new way to think about and envision and enact the American revolution. So when Grace helps to build the Freedom Now party, she's the only non-Black person in this self-consciously all Black political organization whose goal is not to achieve integration, but to try to realize some power political power for African Americans.

Grace Lee Boggs: The word power strikes white people as something dangerous, threatening. And we were only talking about Blacks being in office.

Anita Johnson: That was Grace Lee Boggs. And again, you're listening to "American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs". Here's the film's producer and director Grace Lee.

Grace Lee: Back in 1963, Grace was still speaking as an outsider.

Grace Lee Boggs: I want to make very clear that I do not claim in any sense of the word to be a Negro. I have not lived all my life as a negro. I don't think anyone who hasn't really can speak for the Negro.

Grace Lee: But once she becomes a Black power activist, she starts using the word "we."

Grace Lee Boggs: In the Black movement, when we were demanding first-class citizenship, we were saying we were being denied that. We were very ethical, but we wanted more than that. Right.

We wanted to become part of the people who took responsibility for the country.

Stephen Ward: So by 1966, 67, she's well known, particularly in Detroit circles, but also nationally as a Black power figure.

Grace Lee Boggs: And I became so active in the Black power movement that FBI records of that time say that I was probably Afro-Chinese.

Anita Johnson: You're listening to "American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs", on Making Contact. To hear this entire program and others, check out our website radio project.org. Subscribe to our podcast. Sign up for Making Contact updates. Take our survey or join the conversation on Facebook or Twitter. Now back to the film "American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs."

Grace Lee: In 2008, Grace invited me to a tiny island off the coast of Maine.

Anita Johnson: That's Grace Lee producer and director of "American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs," describing an experience with Ms. Boggs that brought her closer to understanding the rich and multifaceted life that the social activist led.

Grace Lee Boggs: So if you will be on that side of me as we go across.

Grace Lee: Okay.

Grace Lee Boggs: Uh, I feel more comfortable.

Grace Lee: She and Jimmy began coming here every year after the turbulent summer of 1967.

Grace Lee Boggs: Gets more rickety by the day.

Grace Lee: I hope that coming here would help me understand. How she went from being the sixties militant to the woman I know today.

Grace Lee Boggs: As we sat here against the background of the ocean, of the trees, we just began talking and we started these conversations, which are now published as conversations.

Grace Lee: Every summer Grace and Jimmy would join their old friends, Lyman and Freddy Paine in Lyman's family home. They had known each other since the 1940s, when they worked with CLR James. Over the years, we had these long conversations.

Stephen Ward: Of course, in the revolution , rebellion was a big question. You had long lived for a day when the mass would be in motion.

And of course in his way, if the motion go on, what are the depths of it and what changes have to take place and people in order to bring about a revolution?

Grace Lee Boggs: Talking together, we were able to create a kind of consciousness among ourselves. And I think we realized a rebellion is an outburst of anger, but it's not revolution.

Revolution is evolution towards something much grander in terms of what it means to be a human being. You can have discussion, you can have a meal, you can plot whatever. We plotted picket lines. We plotted anything we wished to do. At the end, it was always okay. Let's put on some music and let's relax. And music relaxing and dancing are part of the thing.

So then. Welcome come to the house. Pretty good shape.

Freddy Lyman: I started going in 78 and then went back every year, uh, with Grace and Jim. It was my first exposure to talking about what's this all mean? Where are we headed?

Grace Lee Boggs: Ideas matter. And when you take a position, you should try and examine what its implications are. That it is not enough to say this is what I think this is what I feel and leave it at. I can remember, for example, do you mind if I just pay him for change my tape for a moment? Um.

Grace Lee: Grace has stacks of these old recordings, physical proof of how much she values conversation.

Grace Lee Boggs: We're the only living things that have conversations.

So, so, you know, when you have a conversation, you never know what's going to come out of your mouth or out of somebody else's mouth.

Freddy Lyman: [Expletive], Grace. Come on.

Grace Lee Boggs: Freddy, I'm sorry. I don't this is [expletive]. I really don't. Okay. I'm sorry.

Grace Lee: It all goes back to hagle. For Grace, conversation is where you try to honestly confront the limits of your own ideas in order to come to a new understanding.

Nancy: Talk is cheap, but can talk about their feelings about what was important about their feelings, and then turn around and say that to the mother.

Grace Lee Boggs: I really, really, really get.... I I'm sorry, when you just say talk is cheap like that. I can't, I can't. I find it very, very difficult to take. I wanna tell you honestly, that talk was not cheap!

Nancy: You're making an ... you're saying. No, you're saying you're not listening. You're saying that we can talk about what's important in a revolutionary movement, but we don't have to act like it.

Freddy Lyman: Grace was hard on people. There's no question about it.

Archival tape: Grace, I think what Nancy's raising is...

Freddy Lyman: You know, I sometimes think she didn't mean it personally, but she would be so intent on whatever her idea was and be so sure that she needed to push you in that. And if you resisted, she'd get mad.

Nancy: It's hypocritical.

Grace Lee Boggs: Well, I, I'm sorry, this, this, you know, I feel the number of adjectives that you are using with regard to are, um, very excessive. I really do. And I think you really should look at it.

Grace Lee: Did she make people cry?

Freddy Lyman: Oh God. Yes. She made all kinds of people cry, myself included, but all kinds of people. Yeah. I could probably give you a rather long list.

Grace Lee Boggs: Two, three. Freddy in the afternoon would make cranberry sauce. And I would read to her.

"Jackson understood that the scars carried by white workers, were as damaging to our national well-being as the scars carried by African Americans, the hidden injuries..."

There were times when expanding our imaginations is what is required. The radical movement has over emphasized the role of activism and underestimated the role of reflection.

Anita Johnson: Grace Lee Boggs was passionate yet practical. She was able to develop empowering micro-level community programs in response to oppressive macro level societal problems. She represents the beauty of fighting for human rights in the face of adversity while also creating a life of joy and love. By shining a light on Grace Lee Boggs work in Detroit, the film "American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs" reminds us to never underestimate the power of local place-based community building.

Grace Lee Boggs: I grew to love Detroit and to feel responsible for Detroit, that I was able to grow and find one thing after another. And trying to learn from everything that I try. That's the only way. I mean, the illusion is the quick answer leads to burnout.

Grace Lee: As Grace struggled to understand the violence that was devastating her community. She returned to the evolving ideas of Malcolm and Martin.

Grace Lee Boggs: Malcolm really struggled. And towards the end of his life began to be critical of Black nationalism and went down to make common cause with King. After Malcolm was killed, I would attend these meetings and I would see young people. 14 15, 16 year olds getting up and limiting Malcolm to sort of meet violence with violence. And I knew something was terribly wrong.

Why is nonviolence such an important, not just a tactic, not just a strategy, but an important philosophy? Because it respects the capacity of human beings to grow. It gives them the opportunity to grow their souls, and we all have that to each of them.

And it took me a long time to learn that.

I suggest you do some more thinking.

But as I saw the violence increase in our cities, I wondered would it have been possible to combine Malcolm's militancy with Kings non-violence? I began reading King much more carefully. In 1965, King flew to California and he was amazed to hear that these young people had never heard of him, that they thought non-violence was foolish.

And he began saying, "what do I do about that?"

Martin Luther King Jr.: I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the word "revolution," we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing oriented society to a person oriented society.

Grace Lee Boggs: King said, what are young people in our dying cities need are direct action programs, which enabled them to transform themselves and their institutions at the same time.

It's an incredible city. That's one of the things that's very exciting about Detroit also, because it's not going to be, reindustrialized .It's because something else has got to come out of it. And we're, we're really thinking about how do we rebuild it now? How do we take this space? How do we make something new out of it?

Grace Lee: In 1992, Jimmy and Grace helped launch a program called Detroit Summer to transform the vacant lots and buildings of Detroit, hoping that in the process, young people would transform themselves.

Grace Lee Boggs: Thank you for coming back. When they can see themselves making a difference, they also become different. That has to be part... an integral part of the verses of revolution.

Youth in Detroit Summer: I have one line. Grace gave it to me Friday morning, the part about organizing work, we want to bring the neighbor back to the hood.

Grace Lee: How are you doing?

Youth in Detroit Summer: So I was 16. And I volunteered to be a part of Detroit Summer. Um, I was actually the very first person to sign up and I had profound questions. Why does everybody talk about Detroit in the past tense? You know, it's just a sty I'm living in Detroit now. And I don't want to feel inferior all the time because Detroit isn't the city that it used to be.

Anita Johnson: Grace Lee Boggs was a complex woman. She knew the ins and outs of political activism, community building, philosophical theories, you name it. Her brilliance was matched by that of her husband, Jimmy Boggs, a Black auto worker and political activist. Together they made a strong and inseparable team lifting up the voices of Detroit's marginalized populations, but as an individual, in her own right Gracie Boggs represented another population that was also overlooked and underrepresented: Asian Americans. It was not until late in life, when she was asked to write an autobiography, that she really began to reflect on her role as a social justice advocate and embodiment of Asian American activism.

Grace Lee Boggs: People began asking me to speak on the Asian American movement. And I discovered my ignorance. People are so searching for icons that they sort of fixed on me. Even though I wasn't an Asian American icon. The varieties of Asian Americans that I see around here is so, it's so enormous, I mean, it's just incredible.

Scott Kurashige: I met Grace when I was still struggling with a sense of, you know, where do Asians fit in, in a world that's mostly white and Black? Yeah. When we think about Grace in the 20th century, she is very much an outsider. In the 21st century. She represents the uniting of people from different races and different backgrounds in a way that is now defining America.

Grace Lee Boggs: Let me just make a challenge to you. Okay? With people of color becoming the new American majority in many parts of the country, how are we going to create a new vision for this country? A vision of a new kind of human beings, which is what is demanded at this moment.

I can't begin to tell you the number of young people who come to Detroit and they come in order to be part of this new world that is being created.

Scott Kurashige: How many, how many have you been to Detroit before? You're going to see a lot of abandonment, but you'll see it's about rebuilding a new way of life for people who've been completely left behind by a capitalist system, which has gone elsewhere looking for profits.

Scott Kurashige:People had to find new ways to promote economic survival when unemployment was reaching upwards of 50% as it has now. Grace goes at the forefront of the movements in Detroit that were developing urban gardens and eventually even bigger urban farms.

Unidentified Speaker:Most gardeners, I say 90% of the gardeners don't garden on land they own. They're gardening on vacant, lots that are next to their house or across the street they paint.

Grace Lee Boggs: To think of gardens as the basis of hope was something that was unthinkable just a few years ago.

Unidentified Speaker: As Detroit summer was emerging and they were doing murals and they were doing gardens, a question I was always asking was, what does this have to do with the movement? They're nice projects. I think what I begun to understand is individuals who experience and get involved in those projects become leaders, become thinkers, become compassionate people that see themselves as makers of history.

Grace Lee Boggs: It starts with imagining the kids in this space and the community. And I was going to grow more by trial and error than going to grow by blue fringe.

Unidentified Speaker : That's always my downfall. I think I can get it. Perfect. And then do it as opposed to knowing that the, that I, you do it by making mistakes.

Grace Lee Boggs: Yeah. You make your path by walking.

Music: Detroit in the summer. It's more than a season. When I moved to the city was the core of the reason can I clarify all the distortion you seeing got to break your mind out of prison, while the warden asleep.

Unidentified Speaker: one of my favorite quotes by Grace is that creativity is the key to human liberation.

Unidentified Speaker: You begin to shape the idea what you mean by quality education, you know.

Grace Lee Boggs: And so first of all, everybody who talks about quality education is really talking about how people become more like white people and advanced in the system.

Unidentified Speaker: I don't, you know, I, I, I beg to differ with you on that.

Grace Lee Boggs: Most people think of ideas as fixed ideas. But ideas have their power because they're not fixed, that once they become fixed, they're already dead.

Anita Johnson: Grace Lee boggs can not be put into a Boggs or easily defined. She broke barriers to dedicate her life to uplifting disenfranchised communities.

She represents perseverance power and her legacy lives on through the social movements of today and the countless young activist.

You've been listening to the documentary "American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs." Special thanks to the producer and director Grace Lee for use of the film and raptivist Invincible for use of the song "Detroit Summer."