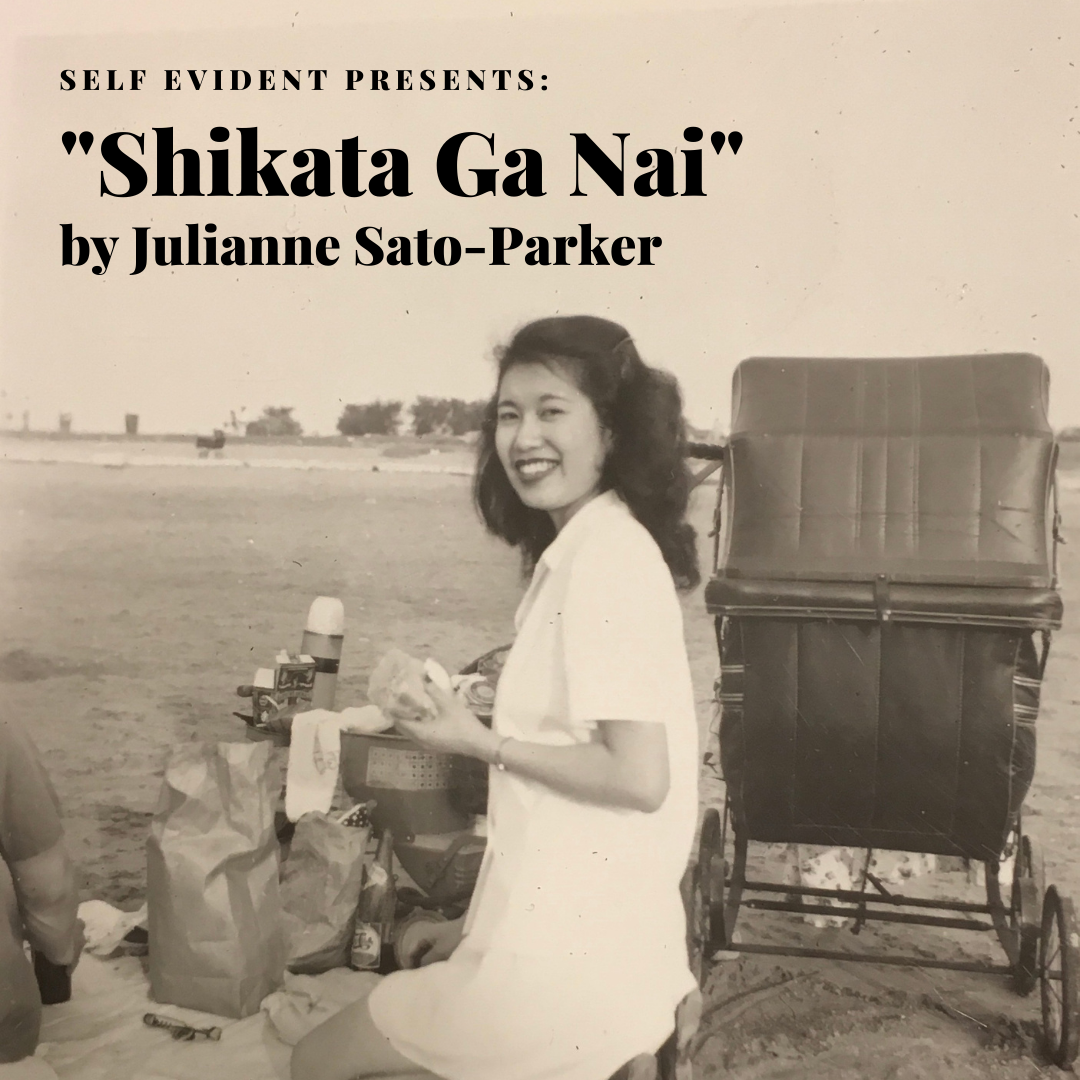

Self Evident Presents: “Shikata Ga Nai” (by Julianne Sato-Parker)

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

Julianne Sato-Parker first heard the phrase, “Shikata ga nai” while watching a video series of interviews with Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals who were incarcerated by the U.S government after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese phrase translates to, “It cannot be helped.” It reminded Julianne of her grandmother, who has always said a similar phrase when navigating life’s unpredictable twists and turns: “That’s just the way the ball bounces.”

But the phrases may not be as passive as they seem. As Julianne became fixated on how one became the other, she turned to her grandmother for answers — and to better understand how we find resistance and resilience, even in things as seemingly simple as a phrase.

Resources:

A longer version of this story — titled “That’s the Way the Ball Bounces” — first aired on Asian Americana, where you can even hear host Quincy Surasmith’s interview with Julianne about the making of this piece. Check it out here.

Nisei Soldiers Break Their Silence by Linda Tamura

Credits:

Produced and written by Julianne Sato-Parker

Edited by Julia Shu and James Boo

Scored and mixed by James Boo

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

Music by Blue Dot Sessions

Additional music (“Umbrella Pants” and “I Knew a Guy”) by Kevin Macleod (licensed under CC-BY-4.0)

Hail archival tape via freesound.org

Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts Creator Program — and with the support of our listener community.

Transcript

Intro

CATHY: Hey, it’s Cathy. Today, we’re presenting a story by producer Julianne Sato-Parker.

CATHY: Julianne originally debuted a longer version of this piece on the podcast Asian Americana, which we’re linking to in our show notes. And we got really excited when she shared her work with us, and asked if we could collaborate on bringing it to Self Evident, too.

CATHY: Here’s Julianne with the story.

SOUND: The phone rings, and an elderly woman picks up

Bobbe: Hi Julianne!

Julianne: Hi Bobbe, how are you?

Bobbe: How are, how are you doing?

Julianne: I’m good!

(The phone conversation fades behind Julianne’s narration)

Julianne (Narrator): Ever since I was a kid, my grandma and I have called each other a few times a week.

Bobbe: Doing the crossword puzzle...

Julianne (Narrator): She used to call me every Thursday to remind me the rotisserie chickens at Safeway were going on sale the next day, or to tell me when Walmart started selling Mentos for 5 cents cheaper than Rosauers.

Julianne (Narrator): I’m just as quick to call her with good news. She’s always been my most enthusiastic cheerleader. She’s as eager to shower me with pride and praise for getting a good grade as for finding a good discount on a pair of shoes.

Bobbe: I was just thinking of calling you because I heard you were making asparagus tonight.

Julianne: I did make asparagus tonight. It was really impressive.

Julianne (Narrator): Lately, we don’t have as much to talk about. It’s the spring of 2020 and we’re all in the midst of waiting out the coronavirus. My parents moved my grandma into their house when the virus first broke out in nursing homes in Seattles in the hopes it would lower her risk of exposure, and I’m finishing up school remotely. So our lives have gotten pretty quiet.

These days, when we call, we usually start by talking about the weather…

Bobbe: It’s beautiful weather. We’ve been so lucky. A really beautiful spring!

Julianne (Narrator): And then I get an update on where she’s at with her latest jigsaw puzzle…

Bobbe: This is a tough one. The pieces are smaller, and they all look alike!

Julianne (Narrator): The only entertaining thing I have to offer her right now are updates about my latest quarantine-inspired “virtual dating” experiences. So I’m really leaning into it.

Bobbe: Say, what’s been going on with your phone dates?

Julianne: We upgraded! We’re not just doing a phone call, we’re doing a FaceTime! I dressed just my top half. Bottom half is pajamas!

Bobbe: (Laughs, amused) Oh, you have got to be kidding me.

Julianne (Narrator): But inevitably, the conversation always turns back to COVID.

Bobbe: I can’t believe this quarantine. Everyone. It’s everyone. Oh this world is just at a standstill.

Bobbe: Isn’t that crazy? I mean everything is crazy now.

Bobbe: Gosh, how long is it gonna last?

Bobbe: I’ve never seen anything like this…

Bobbe: I think we are all going to live through it.

Julianne (Narrator): And then, without fail, the conversation ends with…

Bobbe: Well, that’s just the way the ball bounces.

MUSIC begins

Julianne (Narrator): This is my grandma’s go-to saying whenever something bad happens.

Bobbe: That’s just the way the ball bounces.

Julianne: She says it all the time. When I was growing up, she’d say it if my team lost a soccer game, or if I called her to get some sympathy when I was home sick from school. “Oh, you poor thing,” she’d say. Then she’d take a long inhale, and as she released her breath, she’d say,

Bobbe + Julianne: “Well, that’s just the way the ball bounces.”

Julianne (Narrator): She always shrugs when she says it. Even on the phone, I know she’s shrugging. The saying itself is kind of like one big shrug.

Julianne (Narrator): But, this phrase is kind of the antithesis to my response to the pandemic.

Julianne (Narrator): I move through the day trying to focus on work, but ultimately falling down endless Internet rabbit holes: watching videos inside NYC hospitals, reading articles, looking at modeling charts.

Julianne (Narrator): I grasp for any control I can — sewing face masks, scrubbing grocery packages with bleach, outlining contingency plans for every possible combination of who might get sick in my family.

Julianne (Narrator): I stay up at night, often too anxious to sleep, imagining the worst case scenarios in vivid and dramatic detail.

Julianne (Narrator): So the idea of shrugging this off seems kind of impossible. But every time we talk, my grandma keeps saying this phrase:

Bobbe: That’s just the way the ball bounces.

Julianne (Narrator): She updates me on her puzzle. She tells me how many hummingbirds she counted in the yard that day. She asks about my phone dates. And she repeats these words.

Julianne (Narrator): Every time we talk.

Julianne (narrator): My grandma stands just higher than 4 foot 10 these days, with a grey perm that circles her head kinda like a storm cloud. She’s elegant. Graceful. Her nails are always polished with shades of pinks and reds with names like “Born to Sparkle” or “Make Him Mine.”

Julianne (narrator): She listens to classical music with her eyes closed. She keeps tissues stuffed up her sleeves and pulls them out like a magician, handing them to you to wipe down your chair at a restaurant before you sit, or to wrap up the last remaining bites of a sandwich to store in her purse for later.

Julianne (narrator): We’ve always been close. But it wasn’t until I started college, about a decade ago, that I got to know a fuller version of her. A version beyond the charming, loving grandma who slept next to me whenever I stayed with her or who slyly passed me candy during my sister’s violin recitals.

MUSIC ends

Julianne: Okay, I think we are... rolling!

Bobbe: Oh hi. My name is Dorothy H. Sato, and I was born in 1923.

Bobbe: And I just love it here… the mountains right behind me, Mt. Hood. And it’s a beautiful place to live.

SOUND: Wind blows through chimes, and sprinklers run

Julianne (Narrator): We sat on her patio that day, facing the outer edges of the pear orchard that’s been in my family for nearly a century.

Julianne (Narrator): I’d like to tell her whole life story. About her parents immigrating from Japan to America. About her father working in the lumber mills in Washington until he died aboard a ship back to Japan when my grandma was 5 or 6.

Julianne (Narrator): It’s tempting to tell stories about my grandma’s childhood growing up in Seattle’s Japantown, where her mother raised her and her four siblings in the back of a small hotel.

Bobbe: We grew up in a hotel, up until…

Bobbe: Our wants were too much. Five kids scrambling, you know...

Bobbe: We went swimming to Mt. Baker quite often.

Bobbe: Sometimes we had to walk…

Bobbe: When he would come home for dinner or something, you know, he’d yell up, and he’d say, “How’s the weather up there?” saying, “What’s mom like, today?”

Bobbe: Guys would come and ask us to dance, and my brother would always be there, too, with his friends, and they’d always come and dance with me.

SOUND: A film reel starts to spin

Julianne (Narrator): But the story I really want to tell begins on December 7, 1941.

Bobbe: When Japan declared war, I was in a movie theater. And all of a sudden on the intercom it said, "Anyone in uniform is to report to their station right away." But they didn’t say why, and I didn’t know until I came home and turned the radio on and found that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor.

SOUND: The film spool runs out

Julianne (Narrator): The United States entered WWII that day, and within the country, discrimination brewed against Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans.

Julianne (Narrator): A quick side note — it’s a mouthful to say Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans, so I’m going to start using the Japanese term “Nikkei” from here on out to reference the Japanese diaspora.

Julianne (Narrator): Anyway, after Pearl Harbor, the Nikkei became the target of a lot of discrimination in the US, both by the government and by their neighbors.

Archival tape of a news broadcast: The city of New York has already ordered all Japanese nationals to remain off the streets.

Bobbe: They imposed a curfew on all Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans.

Bobbe: But my brother, he would invite his friends over to play poker, and they’d play down in the basement, but put blankets on the window so they couldn't see in.

Archival tape of a news broadcast: The Department of Justice is moving rapidly to contain all Japanese nationals.

Bobbe: We were supposed to disappear into the sunset. If you were Japanese, don’t let people know you’re Japanese. I was American...

Archival tape of a news broadcast: This will mobilize the efforts of the whole American people.

Bobbe: … but I guess that didn’t matter later, when they evacuated us.

Archival tape of a news broadcast: Nothing matters anymore now, except national security.

Julianne (Narrator): That spring, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which ordered the removal of all people of Japanese ancestry from their homes and into US concentration camps.

Julianne (Narrator): My grandma, who was 19 years old at the time, and her family were evacuated from Seattle and sent inland — first to a camp in Puyallup, Idaho where they lived in horse stalls on a fairground. And later to a camp called Minidoka near Twin Falls.

Bobbe: It was awful.

Bobbe: It was just absolutely awful. The wind was blowing. The dust was blowing, and I mean it was just absolutely awful! I thought, well what are we doing in a hell hole like this? That’s what it was, and everybody — just not me or my family — it was everybody that went there, you know? It was terrible.

MUSIC begins

Julianne (Narrator): One summer, I was watching a video at a museum. It was a series of interviews with Nikkei who were incarcerated. A woman was describing the experience, and then she shrugged and said, “Shikata ga nai.” Then another person in the video said the same phrase. Then another. The subtitles translated the phrase to: “It cannot be helped.”

Julianne (Narrator): After that, I started to notice the phrase all over the place, and it was usually used in the same way: to characterize the Nikkei as this passive and obedient group of people who rarely resisted their imprisonment.

Julianne (Narrator): But this phrase is not a uniquely Japanese sentiment. It’s actually super universal. A lot of languages have their own version.

Julianne (Narrator): In Farsi, “Hamini keh hast,” (HAM-ANI- KAH- HAWST) means, “It is what it is.”

Julianne (Narrator): In French, “c’est la vie,” means, “Such is life.”

Julianne (Narrator): They all essentially say the same thing: accept life as it is.

Julianne (Narrator): But I really hated how the Japanese version was used. I’m not sure I really understood why. I think I just hated how fatalistic it was.

Julianne (Narrator): I’ve always seen my grandma as this really strong-willed, self-assured person, and this phrase seemed to contradict that.

Julianne (Narrator): The adoption of “Shikata ga nai,” to me, made people like my grandma seem... kind of spineless. Passive, complacent, even.

Julianne (Narrator): I never said this to my grandma. But I did wonder about it sometimes.

Julianne (Narrator): Why didn’t they protest? Why did they go so quietly?

MUSIC ends

SOUND: Phone rings

Bobbe: Julianne!

Julianne: Hi Bobbe!

Bobbe: How are you today?

Julianne: I’m good, how are you?

Bobbe: I’m doing fine!

Julianne: You know that phrase I keep asking you about?

Bobbe: Yeah, “Shikata ga nai”?

Julianne: What does it mean?

Bobbe: Well, “It can’t be helped.”

Bobbe: I’ve heard that all my life. My mother always said that when something happened beyond her control, and I think she passed it onto us.

Julianne: You didn’t really say that particular phrase growing up, but you always said, “That’s just the way the ball bounces.” You know?

Bobbe: Yeah. That’s almost how that interpretation —

Julianne: It’s almost like the phrase, “shikata ga nai,” got eventually replaced with, “That’s just the way the ball bounces.”

Bobbe: I never thought of it like that, but as you’re mentioning it, you are right.

Julianne: I was going to ask if you feel like you’ve always had that kind of attitude.

Bobbe: Yeah, I think I have, that whatever happens, happens. There are things you have no control over.

Julianne: Do you think that having that attitude helped you survive the internment, and like, the years during and after the war?

Bobbe: Maybe, maybe so.

Bobbe: Whatever happened, we just went along without protest.

Julianne (Narrator): My grandma often calls the formerly incarcerated Nikkei “the Silent Americans.” It’s how she describes their largely non-resistant removal and incarceration.

Bobbe: We were herded like sheep. We never protested. We never protested. We did exactly what they wanted us to do.

Julianne (Narrator): This lack of protest is something that’s always been on the forefront of my grandma’s memory.

Julianne (Narrator): But the thing is, there was resistance among the Nikkei. There were swells of protest throughout the concentration camps: there were draft resisters, conscientious objectors, organized riots, strikes, work stoppages.

Julianne (Narrator): There were the No Nos, who the government deemed disloyal to the US. Some Nikkei were sent to federal prison. There were others who filed lawsuits.

Julianne (Narrator): And then there was everyday resistance within the camps — sabotaging the fences that locked them in, smuggling in liquor, graffiting the barrack walls.

Julianne (Narrator): But most of this resistance was suppressed or erased. Our history’s collective memory propagates this myth — that the Nikkei were complacent captives.

Julianne (Narrator): Historical accounts describe a group of people who silently accepted their fate. Whose reaction to their mass incarceration was often summed up by the common use of the Japanese phrase: shikata ga nai… “it cannot be helped.”

Julianne (Narrator): My grandma’s memory has always supported this narrative. Until for the first time a few days ago when something shifted in her re-telling of that time.

Bobbe: Whatever happened, we went along without protest.

Bobbe: But I think that’s just life, you know?

Julianne: Yeah. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

Bobbe: I mean, we protested, but the people didn’t hear us.

MUSIC begins

Julianne (Narrator): That was the first time I’ve ever heard her say something like that: “We protested, but no one heard us.”

Julianne (Narrator): Which, for the first time, made me wonder… who should really bear the burden of this title, “The Silent Americans”?

Julianne (Narrator): To be silent implies you had a voice to begin with — a voice people would listen to. But how much of a voice did my grandma and other Nikkei truly have during the war?

Julianne (Narrator): Who were “The Silent Americans”? The Nikkei, who under threat of law, physical force and discrimination, were intimidated into compliance and actively silenced when they did resist, or the white Americans who had the collective power to support the Nikkei and oppose authority... but didn’t use it?

Julianne (Narrator): I felt a lot of shame when I realized this. That through all the years of interviewing my grandma and all the times she identified her own silence as though it was something to be ashamed of, that I never once thought to say to her: “You weren’t the silent one. ‘The Silent Americans’ is not your title to bear.”

Julianne (Narrator): The problem with that title is the same problem with how the phrase, “It cannot be helped,” “Shikata ga nai,” is often used. They both seem to imply that the Nikkei consented to their incarceration. That it was their own passivity that allowed for it to happen.

Julianne (Narrator): Of course, that wasn’t true.

Bobbe: I mean we protested, but the people didn’t hear us.

MUSIC ends

Julianne (Narrator): My grandma spent about a year and a half surrounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers, waiting for her imprisonment to end.

Julianne (Narrator): When she was released, she took an eastward train to Chicago where she spent about seven years, trying to pick up where her life had left off.

Julianne (Narrator): She worked, she dated, she spent summer days by Lake Michigan. Eventually, she met and married my grandpa, a Japanese American farmer from Oregon.

MUSIC begins

Bobbe: He really came after me. I mean, when he met me, he wanted to marry me. I mean, you know? And I’m thinking, “What?”

Bobbe: He was a country boy, and I’m a city girl. My God, I get over there, and they have chickens on the farm.

Julianne (Narrator): My grandpa’s early years after the war were different from my grandma’s time in Chicago. His small, agricultural community in Oregon was fuming over the return of its Japanese community members. He slept in his basement, scared of what his neighbors might do to him at night. Stores wouldn’t sell him groceries or gas. The local newspaper published articles with headlines that read, “JAPS NOT WANTED HERE,” with the signatures of every community member who agreed.

Bobbe: Ray came back to a hot bed. They were not welcome. They were scared for their lives. They didn’t know what would happen to them.

Bobbe: But he held his head high, went back to his farming. And he was an outstanding member of the community all through his life. But it was very sad, I mean, it was a very hostile place.

Julianne (narrator): By the time my grandma arrived from Chicago about 7 years after the war ended, newly married and fresh to farm life, things had calmed down. There wasn’t as much blantant and hostile discrimination as there was in the early days after the war. But my grandparents still protected themselves and their kids from discrimination in anyway they could.

Bobbe: And the feeling when we came out of the war was: assimilate yourself to the American society. Don't let people know you're Japanese. Don't speak Japanese in public. Let people know you're American citizens.

Bobbe: And that’s what it was. We were told not to go around saying, “I’m a Japanese American,” you know? And I think that was the underlying thing, which was absolutely wrong. But that’s what happened.

MUSIC ends

Julianne (Narrator): I always spent hours snooping around my grandma’s house when I visited. She keeps everything. Her house is a treasure trove of newspaper clippings, stylish outfits from the 40s, trinkets from her travels. I once found a box of teeth my mom claimed to be her molars.

Julianne (Narrator): My grandma knew I snooped. She wished me luck when I told her I was heading down to the basement. I think she even started leaving things out for me to find like her high school yearbook or a film camera of my grandpa’s.

Julianne (Narrator): On one of my ritual snoops, I found a tiny silver ring. It fit only on my pinky finger and had the initials H.S. carved into the round, flat face. When I showed her the ring, I asked who it belonged to. She told me it was hers.

Bobbe: My mother told me that she had named me after the seashore, “Hama.”

Julianne (Narrator): But in the early days of a brewing war, my grandma and her siblings all changed their Japanese names to American names.

Bobbe: Why I picked “Dorothy,” I will never know.

MUSIC begins

Julianne (Narrator): I’ve mourned the loss of my grandma’s name for years. Along with the loss of whatever else she had to let go of — of language, of traditions, of all the things I couldn’t even recognize but felt went missing in my family.

Julianne (Narrator): I think that’s why I felt so compelled to understand my grandma’s story. I wanted to feel connected to these things that were lost. I wanted to find them, pick them up and reform them into something whole. Something clear, something identifiable.

Julianne (Narrator): I kept thinking I might unearth some fundamental lesson I wanted her to pass along to me, like a physical heirloom I could inherit.

Julianne (Narrator): When I realized this funny phrase my grandma always said to me growing up was maybe just the assimilated version of a sentiment with deeper roots… I felt like I had unearthed that thing.

Julianne (Narrator): Somewhere along the way, “Shikata ga nai” became, “That’s just the way the ball bounces.”

Julianne (Narrator): Hamako became Dorothy.

Julianne (Narrator): But everything that made my grandma who she was was never lost or left behind. Some of it just got covered up by something else.

SOUND: Julianne parks and gets out of her car

Julianne (Narrator): A few days ago, I went to visit my grandma. I parked at the bottom of my parent’s driveway, laid a towel on the pavement, and sat down.

Julianne (Narrator): My mom opened the door, waved, and disappeared back inside.

Julianne (Narrator): Then my grandma’s grey perm appeared in the doorway.

Julianne: Oh, hi there! It’s so good to see you — I know, it’s so bizarre.

Bobbe: The flowers are beautiful.

Bobbe: So how’ve you been otherwise?

Julianne (Narrator): The visit didn’t last long.

Julianne: Uh oh!

Julianne: It’s starting to hail!

SOUND: Tiny hailstones land

Julianne (Narrator): She shooed me away and shouted for me to get into my car, to drive straight home, so I wouldn’t catch a cold.

Julianne (Narrator): I sat in my car, waiting for the hail to pass, watching the small ice chunks bounce off my windshield.

Bobbe: (echoing slightly) That’s just the way the ball bounces.

MUSIC begins

Julianne (Narrator): I thought about how faithfully and firmly my grandma has repeated this phrase to me lately — a steady reminder in a moment of huge uncertainty.

Julianne (Narrator): I think the phrase had more than one meaning. And it depended entirely upon who was using it.

Julianne (Narrator): When people in authority and people with privilege used these phrases — it cannot be helped, it is what it is, such is life — in the context of injustice… it was to absolve their own inaction, to placate their own passivity, to place the burden of change on the oppressed.

Julianne (Narrator): But the meaning of the phrase I didn’t understand until recently, was how the Nikkei used it during the war.

Julianne (Narrator): It wasn’t until this pandemic hit, and my grandma began to cycle through this predictable repetition of, “That’s just the way the ball bounces,” that I began to understand her use of this phrase.

Julianne (Narrator): Her steady repetition was the opposite of passive. It was a mantra. These words, this attitude helped her endure the injustice of her incarceration. It encouraged acceptance for circumstances beyond her control.

Julianne (Narrator): It was never about complacency. At its most menial, it was a shrug. And at its most meaningful, it was about surviving.

Bobbe: I don't bear any hatred or animosity to what happened to us.

Julianne: Do you remember feeling, like... wronged?

Bobbe: Sure, it wasn’t fun, and we suffered a lot in camp, and all that, but... I lived through it. A lot of us lived through it...

Bobbe: Towards the end I figured, well this is what life has brought us, and… you know, if you keep thinking about how awful evacuation was and how awful people were, then it’s just like cancer.

Bobbe: It grows on you, and pretty soon you’re going to be a bitter old woman.

MUSIC ends

Julianne (Narrator): When my grandma was incarcerated, she accepted what was happening was beyond her control. She made her peace with it and moved forward. When she was released, she made changes to adapt to a world unjustly prejudiced toward her. She made her peace with that, too. and moved forward.

MUSIC begins (light drumbeat)

Julianne (Narrator): That seems to be the real meaning behind these phrases. The ball is going to bounce whatever direction it is going to bounce. All we have control over is how we respond to it. We either change or we accept. Those are the only options. Fretting somewhere in the middle is just suffering.

Julianne (Narrator): I think that’s why my grandma keeps repeating these words to me now. I think she sees me fretting somewhere in the middle and is telling me to change what I can and to accept what I can’t... and move forward.

Julianne: Are you tired of me interviewing you yet?

Bobbe: It’s really something. If I have anything to offer to you, that is great. (laughs)

Julianne: I think you have a lot to offer.

Bobbe: Thank you, thank you.

Julianne: I think there’s a lot of wisdom in the things that you say.

Bobbe: Oh, thank you so much. You make me feel good.

Julianne: I’m sure I’ll call you again with more questions. (laughs)

Bobbe: Okay. (laughs) Okay, great talking to you, honey.

Julianne: Good talking to you. Love you.

Bobbe: Have fun with your next telephone date. (laughs)

Julianne: Oh I will, I’ll be sure to keep you updated.

Bobbe: Okay. (laughs) Buh-bye.

Julianne: Buh-bye.

Bobbe: (laughs)

MUSIC grows (a piano joins the drum)

Credits

CATHY: This episode was produced and written by Julianne Sato-Parker.

CATHY: James Boo and Julia Shu helped Julianne edit, score, and re-master the audio for Self Evident. Our executive producer is Ken Ikeda.

CATHY: Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcast Creator Program. And of course from our listener community.

CATHY: I’m Cathy Erway. Thanks for listening, and till next time, keep sharing Asian America’s stories.

MUSIC ends