Self Evident Presents: “Get Up Stand Up” (by Re:Work)

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

When you get into a taxi, you usually know where you’re coming from, where you’re going, and what you’ll do when you get there. But what about your taxi driver – someone whose work is in constant motion, moving from destination to destination, meeting new people by the hour? What was the road that brought them to this moment, what is the journey they'll take next?

On this episode of Re:Work, by the UCLA Labor Center, join host Saba Waheed as she travels with Javaid on the path that brought him from a small agricultural town in Punjab, Pakistan to driving cabs in New York City.

Reading and Resources:

“Taxi!: Cabs and Capitalism in New York City” by Biju Mathew

Self Evident’s audio story on the New York Taxi Workers’ Alliance Hunger Strike of 2021

Credits:

Produced by Stefanie Ritoper, Saba Waheed, Ob1, and Asif Ahmed. Music supervision by Francisco Garcia Nava.

Transcript

PREROLL MESSAGE

CATHY: Hey, it's Cathy!

CATHY: Today we're sharing a story from our friends at Re:Work Radio, from the UCLA Labor Center.

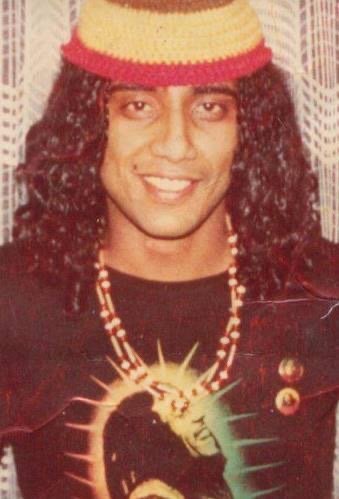

CATHY: It follows a Punjabi taxi driver named Javaid [JAH-vid], as he shares the journey he made from Pakistan to New York City — seeking political asylum, becoming a reggae DJ, then working as taxi driver.

CATHY: If you heard our bonus episode on the New York taxi workers' hunger strike, this piece about Javaid [JAH-vid] will show you just one of the origin stories of that movement.

CATHY: Thanks for listening.

~

Saba Waheed: From the UCLA Labor Center and KPFK, You’re listening to Re:Work.

[MUSIC: Althia & Donna – “Up Town Top Rankin”]

SW: I’m Saba Waheed

Stefanie Ritoper: And I’m Stefanie Ritoper. Re:Work is the redesign of Henry Walton’s legendary 19-year show Labor Review. Each week we bring you real stories that rethink work.

SW: When you get into a taxi, you usually know where you’re coming from, where you’re going, and what you’ll do when you get there. But what about your taxi driver – someone whose work is in constant motion, moving from destination to destination, meeting new people by the hour? What was the road that brought him to this moment, what is the journey he’ll take next?

SW: This week on Re:Work, join us on this journey as we travel with Javaid on the road that brought him to drive cabs in New York City. I met Javaid ten years ago and whenever I would hear snippets of his story, I had a feeling he had something more to tell.

[MUSIC]

SR: Javaid has long salt and pepper hair tied back in a ponytail, a beaded silver necklace, and bracelets that clink when he talks, gesturing emphatically with his hands. He grew up in a small agricultural town in Punjab, Pakistan called Pakpattan that grew cotton, corn and grain. From such a small quiet town, Javaid had a thirst for adventure, even as a small child. He was always testing the limits of what he was allowed to do.

JT: I remember that when I was a 9 year old, my parents went to mecca for a hajj, and they took me and my brother and sister, and we went to Karachi and from Karachi we had to take a ship to go to Saudi Arabia. As I entered in the ship, I just started exploring the ship and I got lost because it was huge and I was just a little boy. It was enthusiastic for me to see that big ship and I never saw before in my life, and I started crying because I got lost. My father was mad at me that you have to be with elders, you shouldn’t have to go alone and it’s not right for you, you don’t understand. But as much more, my father was stopping me, I was trying to more explore. My family was kind of religious and simple family. They were sending me to mosque to pray, but I was running around to go to cinema – to watch a movie because many times, we have two cinemas in our city and the cinema owners know my father and whenever he saw me in cinema, he called my father and my father come on a bike and slapped me, put me on bike and putting me home.

[MUSIC: Ebo Taylor – “Atwer Abroba”]

SW: His rebelliousness streak continued when he got to college, and his parents decided it was time for him to get married.

JT: My parents wanted to marry to my cousin for arranged marriage and I didn’t want it. So my father knew that I like to have a motorbike, so he bought me a motorbike as a bribery so I might be able to understand him. I took my motorbike and ran away from home and I end up with circus people. I start learning riding motorbike in the well of death, like doing the circus, you drive motorbike on the walls.

[MUSIC]

JT: So one time they figure out where I am. They came 2 o’clock night, catch me from the circus, hand tie me to bring back to my city and next day I was married.

SW: It was also at the university that his rebelliousness sparked an interest in politics. He recalls one incident that first opened his eyes to the political workings of his country. When he was young, his uncle got very sick, and he and his parents had to travel to get him medical care.

JT: He was very poor guy, well little small farmer and we took him to Sahiwal, neighbor city that has a big hospital, and its 30 miles away from my town. And we went to that hospital and he was very sick, but there was no bed available and there I realized that the people occupying those hospital beds, they were not even sick. They were just having a furlough from their jobs occupying those hospital beds. And they put his bed outside in open air.

SR: What Javaid is describing was commonplace at the time – in Punjab, temperatures are extremely high, often reaching 115 degrees at the peak of summer. Hospitals though, had air conditioning. That afternoon Javaid encountered wealthier people who had dropped in to cool off from the heat, taking up beds regardless of the fact that others waited for care.

JT: And there I realized how big difference it is culturally, and powerful people are more powerful and poor are more poor. There, things come to my mind that I have to fight for justice, because it’s not right.

[MUSIC: Ariya Astrobeat Arkestra – “Old Ground”]

SW: Javaid continuously referred to his country as overrun by feudal lords. Pakistan is a predominantly agricultural country and yet the land distribution reflects the stark differences between the haves and have nots – 5% of landowners own 64% of the country’s farmland. These differences did not seem right to Javaid.

SW: And so, by the time he reached college, he was active in politics, reading Mao’s red book, inspired by student organizing and taking to heart Prime Minister Zulfiquar Bhutto’s slogan “Food, clothing and shelter.”

JT: Our country is very rich country, we have all kind of resources, we have all kind of land, and we have all four weathers. But, richer are richer and poor are poorer. So, that’s why I had become very much active in student politics.

SR: He dove deep into school and party politics. He was young and unstoppable, and he wanted his voice to be heard. But the times were changing and so were the country’s politics. Zia-ul-Huq (Zia al-HAQ) had declared martial law and ousted Prime Minister Bhutto. One day, while Javaid was in his hometown, the FIA, the Federal Investigative Agency, an agency similar to the FBI, picked him up and arrested him. They never filed any formal charges against him. They detained Javaid for three weeks.

JT: I remember there were always a shackle like 10 of us with one big rod, putting in hand. Or they were laying all night over there and daytime they were shackling us, taking us to field to go to toilet or pee. And then they roll over their big sticks on our thigh and different kinds of tricks, not so visually you can see they got injured, internal injuries, that kind of trick to torture you.

[MUSIC: Zulmat Ko Zia – “Laal”]

SR: Finally, his father had no choice but to pay out bribes to get him released.

SW: This incident shook Javaid to the core, and he decided to leave the country. Germany gave him asylum, so he packed his bags and left. There, he took classes in German and tried working at various factory jobs. A whole new world opened to him as he dove into the adventure of living in a new country and absorbing all that it had to offer.

JT: I was like a hippy type, just a free soul. One day I was watching TV, I saw on the TV they were playing Bob Marley’s music because Bob Marley was sick and he was in the hospital in England and he died that night. That night in Germany, they played all night his music and when I heard his music “get up stand up, stand up for your rights,” I got in love with that music.

[MUSIC: Bob Marley – “Get Up, Stand Up”]

JT: I become a big fan of reggae music. I already had long hair because I always love my long hair, and so I stop combing them, and they become dreadlocks. And I was all day long riding on my roller shoes, just listening to reggae music. I got into, very deeply, into reggae music and I was working as a DJ in a reggae club in Germany for two years.

SR: His education expanded out of the classroom and he encountered a growing left movement in Germany. He read about Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and Marxism. He became more lefty, experiencing intellectual growth and getting involved in local student movements.

JT: I was more and more getting angry about injustice and I got involved with other students doing protests over there and learning more about Che Guevara, and Che Guevara is my second hero, after Bob Marley.

SW: He started making a living as a DJ, living life on roller shoes and reggae, without too much thought about where this would lead him. Back home, he was the eldest of 14 kids, and the first son. Culture and society had laid a clear path that he was expected to take on.

SW: He would return to Pakistan. He would take his position as the head of the family. And he would run his father’s business. So when, in 1988, Zia ul-huq was killed in a mysterious plane crash, the possibility of his return became a reality. Benazir Bhutto, the daughter of the former Prime Minister Bhutto, had returned from exile and had taken over as prime minister. The government dropped the charges that they had filed against him while he was abroad.

SW: After 8 years of living in Germany, Javaid returned home – as a Rasta man, with a soul full of reggae.

JT: I was totally different – with long dreadlocks, I had backpack hanging on my back, big clothes, and poster on my backpack of Bob Marley and my roller shoes was hanging with my backpack.

JT: When I went home nobody could recognize me. They saw what the heck is this, and when they, I take off my hat, and they saw my dreadlocks my father was furious. And I had old jeans and, you know, at that time hardly people know they were just seeing this. Like I’m a follower of hippies and so.

SR: Javaid’s father was furious. This was not the son he had sent away nor the model he expected from his eldest son.

JT: And after 2 or 3 days he was pushing me to go and cut your hair. I said no way, I’m not gonna’ cut my hair, I love my hair, my dreadlocks. I was, in my dreadlocks, I was feeling that soul of reggae music and while I was sleeping, he took a scissors and he cut a ton of my dreadlocks. And when I woke up, I put my hand on my head, and my dreadlocks was gone. That was very, very, sad time for me. It was like when Samson lost his hair, he lost his power. And when I lost my dreadlocks, I lost my soul.

[MUSIC: Mike Brooks – “Oh oh Natty Dread”]

SR: Meanwhile, the political system in Pakistan was once again in turmoil. After just a few years in power, the president dismissed Benazir Bhutto from her position. Javaid stayed away from politics, knowing that if he spoke up, police could easily detain him again.

JT: I never put myself, involved myself any kind of politics and I was just, could not bear, because I saw the difference, between one culture and other culture, and I saw the humanity how when people have rights, how people are living in good condition in their country. And, there is a check and balance, but in my country there was no check and balance, it was in the hands of feudal and bureaucrats. And then in 1990, I left again my country, because I didn’t want to be in that condition where I have always fear that if any, if I speak out loud and any other government come, I will be arrested again.

SW: So Javaid left Pakistan again. He knew one person in New York and decided to take a chance and go to the US. His roundabout journey took him to Dubai, then Egypt. From there, he boarded a plane to LAX.

SW: When Javaid arrived at the airport, he walked straight up to customs. They looked at his passport, an obvious fake, and looked back up at him bewildered.

JT: They wanted to deport me. I said no, I don’t want to go back. You want to arrest me, ok, go ahead. So they arrested me at the airport, they took to one room and it was not only me, there was hundreds of people from different countries. So then they took us to a detention center and there were hundreds of people from all over the world who was trying to enter into America.

JT: Lawyer came to me while daytime. I don’t know what he’s talking, because I was not understanding a lot of English. He got me some signature and he left. And after ten days they announced some names, say “yes”, ok, “come down”, ok, go downstairs, they put us in a van and then around 10 o’clock night, they stopped somewhere that van and they said to everybody “come out”, and then said “ok, well where should we go?”, they said “wherever you want, you’re free.”

[MUSIC: Dirty Gold – “California Sunrise”]

SR: And just like that, immigration authorities dropped off Javaid on the side of the road.

SR: Not knowing what do next, he befriended another Pakistani woman in the group, who took him to her relatives’ house. They fed him and a few hours later, dropped him off at the airport. Javaid took a plane to New York. It was there that his new life in the US began.

SR: He moved to the Bronx. His first job was as a perfume salesman, earning $2.25 an hour and working 14 hour days, 7 days a week. After that he found work in construction, making $40 a day for 10 hour work days. It was a new adventure and he began to explore the city.

JT: My interest was different than other my Pakistani friends. I was like, I like to see the culture, I like to go explore place. I was going to museum, I was going to central park, listen music. I was just all the time, in my free time, I was wandering there. And, sometimes I was sitting in a cafe, writing in Urdu, whatever I see here back home. One of my friends, he has an Urdu magazine and so I was writing in his magazine. But I was thinking to be a journalist, but my English was very poor. I cannot become a journalist. So I thought to do a photography.

SR: His interest in photography is what finally led him to the world of taxi driving. One day he came across a newspaper headline.

JT: I saw a newspaper and the headline of the newspaper was 50 photographs of deceased cab drivers and among them, majority of cab drivers were South Asian: Pakistani, Indians…and those cab drivers who got killed on the job, then it stuck in my mind, to do my photography project on cab drivers. I just don’t want it to be a portfolio of cab drivers, I just want it to go deeply: what happen, what kind of job this is, how dangerous this job is and what happen when one driver got killed on the job. Because he is a half world away, working hard and earning money to send back home to feed his kids and, when he died, who send money to their kids?

JT: I just didn’t want to do, go out and talk to them and taking their photographs. I wanted to explore it. So I made my hack license, and I started driving cab by myself and having my camera with me all the time.

[MUSIC: Bonobo – “Transits”]

SW: And so started Javaid’s career as a taxi driver. But driving a cab wasn’t easy. Most drivers can’t afford a medallion. What’s a medallion? If you’ve been in a New York City cab, you might recognize it. It’s that triangle shaped sign on the top of the cab that certifies it to go on the road as a taxi. Each one costs around a million dollars. So drivers have to lease the medallion through an intermediary company. In addition, they need to pay for the car, the gas and the maintenance. Javaid would spend the first six or seven hours just trying to break even before he could start to earn for himself.

JT: Driving a taxi in New York City is considered second highest stressful job. It’s sixty times more likely to be killed on the job and eighty times more likely to be robbed on the job. And you don’t have any kind of benefits. It’s the only job in which you start with negative money. Any job you go you just work and at the end of work, you get paid. But this is the job before you start you pay from your own pocket. The driver ends up making twenty dollar, he ends up making 40 dollar or he ends up making 100 dollar. It depends on his luck and that depend on his hard work.

SW: And then, there were the drunk passengers:

JT: When you are sitting in a bar you are drinking, keep drinking paying your money over there, but when the bouncer see that now you are going to knock down, they just hail a cab, put them in our cab. Now we are responsible to take them home. But we even don’t know where we have to take them. They fall asleep, or they puked in the car and we cannot lock them inside. Some time we call to the police and police take hours to come there. Maximum they just tell to this guy get out from our cab.

[MUSIC: Dawn of Midi – “Ymir”]

SR: And that gives us just a little bit of insight into driving a cab – while in most other jobs, if things go really wrong, you have a company to complain to, or at least a boss. Driving a taxi, you’re on your own. Though each driver pays a company to lease the cab and the medallion, that company has no responsibility to help when a driver doesn’t break even – or when a driver gets sick, gets robbed, held up at gunpoint, or even killed. What’s more, Javaid saw that average people who got into his cab would treat him differently.

JT: You feel yourself, not a human. You feel yourself as a Pariah of New York. Like, people see you in different way. You drive your private car, it’s different, but when you are driving a yellow cab, people treat you different.

JT: You know this country there was slavery for 400 years, it is not easy to change people’s mind and people see us as immigrants – “oh, you don’t speak English.” Of course I speak but I didn’t go to college – “Oh get the heck out of here, go back to your country.”

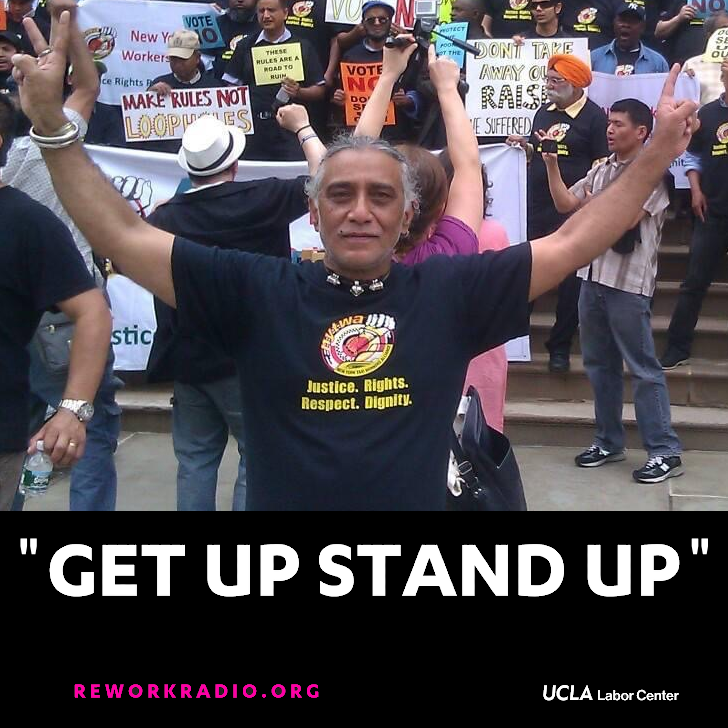

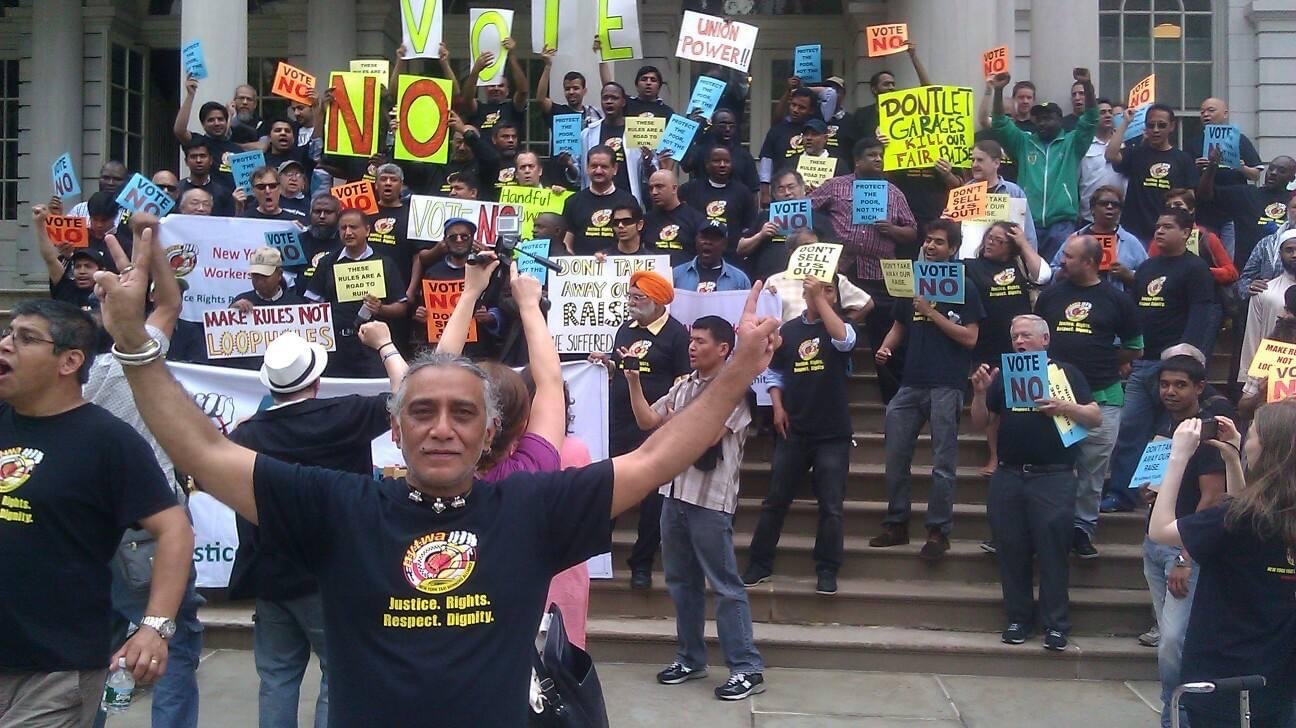

SW: And then, during one of his shifts, Javaid met Bhairavi Desai, who directed the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. She passed him a flyer and encouraged him to come to a meeting. He went and signed up on the spot.

SW: At the time, the alliance was on the verge of taking on the city of New York. Mayor Giuliani was stiffening taxi regulation- he proposed new penalties, increased fees, a probationary period, and drug tests – all in all 17 new rules.

SW: The alliance saw how difficult it would be for the taxi drivers to possibly meet all these new requirements. They planned a one day work action- a day when no cabs would come into the city – demanding the Mayor to meet with them to negotiate the rules. It was an effort that seemed impossible. They had just 500 members. They had no political clout. No one had even heard of them.

SR: But Javaid was inspired, and he jumped into the effort full force. For two years leading up to the action, he joined Bhairavi [BEAR-a-vee] to organize taxi workers- going to airports to find drivers, visiting late night food stands, and catching drivers at gas stations during shift changes.

JT: This is very tirelessly, 24-7 we are into organizing, organizing and organizing. So I was spending more time organizing just working to have food on my table and pay my rent. That was why I could not continue my photography. Instead of being a photojournalist, I became an organizer.

SR: And then the day of the action arrived. Javaid woke up early the morning of May 13, 1998 and he wasn’t sure what to expect.

JT: We were even thinking that oh maybe 65 or 60% are going to be on strike. But when I left my home and took a train to go to city at Penn Station and I didn’t saw any yellow color on 59 street bridge going to city, because yellow color wherever you go, you see yellow color. That was the day that city was colorless. And when I reached to Penn Station, usually at six o’clock morning there are hundreds of cabs on that 7th avenue next to the Penn Station. When I went there, I never saw a single cab there. People were lining up there and it surprised everybody.

[MUSIC: Asian Dub Foundation – “Naxalite”]

SW: The 1998 strike was historic. The city was empty of its 12,0000 cabs. It showed the mayor that drivers were willing to speak up and work together to create change.

SW: Giuliani continued to target drivers after that, but the alliance continued to fight back for years. They won a historic fare increase for drivers, created a drivers bill of rights, developed a health and wellness fund and took on unscrupulous cab companies.

SW: Now, fifteen years later, the taxi workers alliance claims 17,000 members, over a third of all drivers in the city, and have been supporting taxi drivers to organize in cities all around the country as well as building relationships with taxi worker groups around the world. And then, in September of 2011, the National Taxi Worker’s Alliance made history by becoming the first worker center to become formally included in the AFL-CIO.

JT: I cannot imagine that grow up in that small city, could not complete my education, and there I was sitting in White House having dinner with president Obama. Here I am sitting in a big convention hall in the AFL-CIO convention and getting recognition.

[MUSIC]

SW: Javaid may not have chosen the road his father had paved for him – to stay in Pakistan, to take over the family business. Instead his spirit took him some place he never expected. It’s something he could have never imagined, but he wouldn’t have it any other way.

JT: When I was listening, first time I listened to that song “get up stand up, stand up for your rights”, it really gave me a big strength and nothing is impossible. If you think only positive way, you can do if you really want. So if you have courage, if you have some dedication and you want to bring some justice, just do it don’t fear it. And there’s no way that one day you will succeed and this I saw with my own example. Today I really feel very much proud of myself that, ok I could not become a journalist because my English was not that good. I could not become a photojournalist because I could not afford, but, at least I become an organizer and I’m helping a lot. It is really bringing some changes in other persons’ lives. So unite yourself, fight for yourself and never fear, you can do it.

SW: Javaid continues as an organizer. He drives a cab once a week. To stay in touch with drivers, he tells us.

[MUSIC: Bob Marley – “Get Up, Stand Up”]

SR: This show covered the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. Just recently at the 2013 AFL-CIO conference, the delegates selected Bhairavi Desai to become the first South Asian woman and the first worker center representative to serve on the executive council of the AFL-CIO. Thanks to Javaid Tariq for sharing his story with us. To learn more about the alliance, please visit NYTWA.org.

SW: You’re listening to Re:Work a program of the UCLA Labor Center and KPFK. This week’s show was produced by Stefanie Ritoper, Saba Waheed, Ob1, and Asif Ahmed. Music supervision by Francisco Garcia Nava.

SW: We continue to hold on to Henry Walton and the Labor Review’s central principle of solidarity.

SW: And we now have a Facebook page – so please like us! Find us at /reworkradio. You can also tweet your reactions to this show to @ucla-labor or send us an email at rework@irle.ucla.edu

SR: Until next time re-think, re-work!