Episode 004: Pull up the Roots

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode

Three conversations about letting go of something that’s always defined who you are — and becoming the person you didn’t think you were allowed to be.

“Unspoken” - Documentary filmmaker Patrick G. Lee tells Cathy about the unexpected ways that coming out affected his family.

“The Debut” - Producer Preeti Varathan and her cousin Srinidhi unpack complicated feelings about their larger-than-life, coming-of-age musical performances.

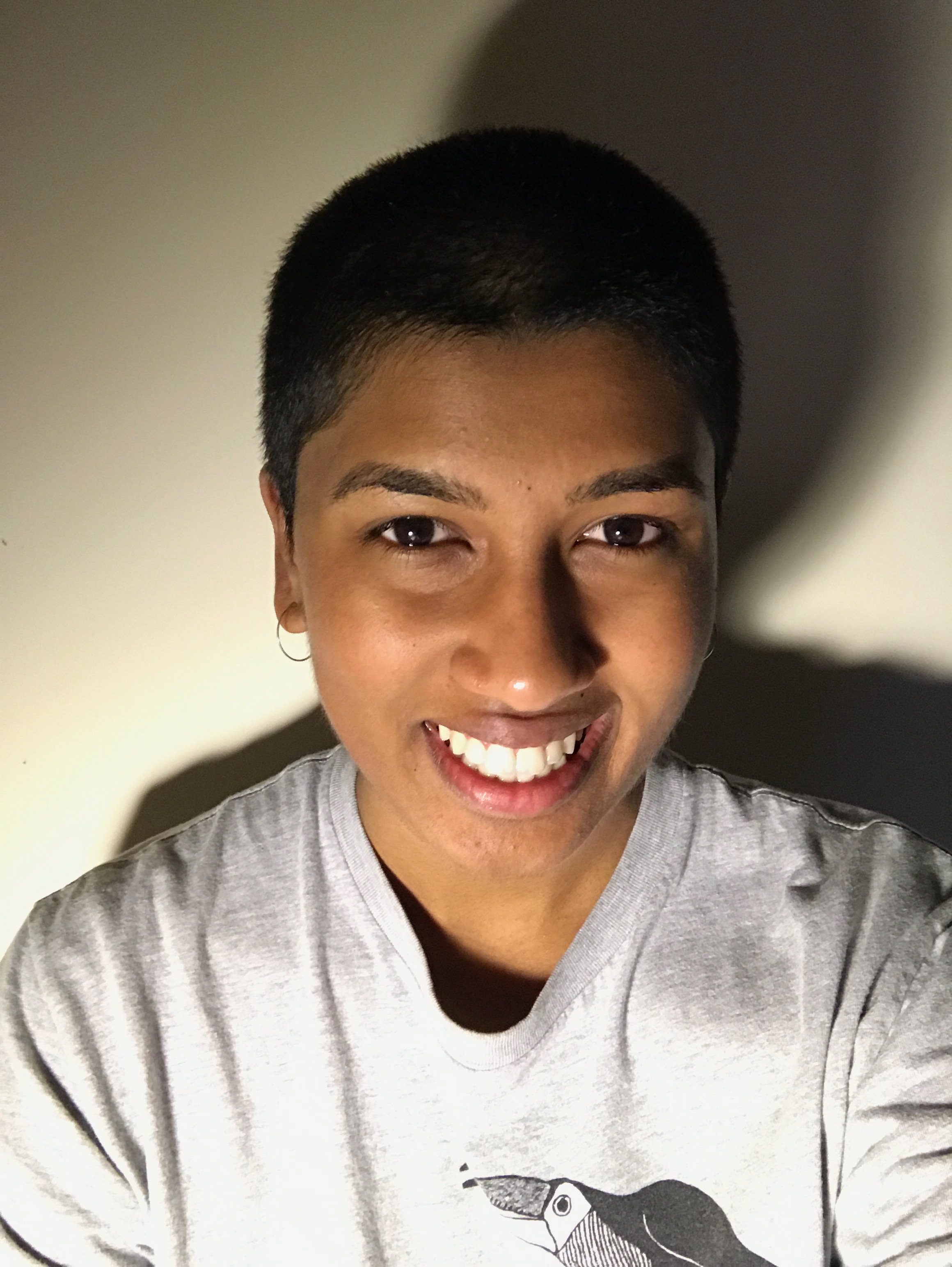

“Buzz Cut” - Old college friends L and Sindhu reunite to talk about why they decided to cut off all their hair.

We need your help!

Please take this 2-minute survey, so we can have better conversations with partners and sponsors and keep this show growing. It’s fast, easy, and anonymous.

Resources and Recommended Reading:

To learn more about Patrick G. Lee’s documentary, “Unspoken,” follow the film on Facebook.

Self Evident and Patrick will screen the film exclusively for our listeners in August, so if you want to see it, subscribe to our mailing list.

There’s more at the intersection of LGBTQIA and Asian American identity than coming out, but our friends at Mochi Mag recently put together this sweet collection of coming-out stories from Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, and Singaporean Americans to celebrate Pride.

And one of our favorite podcasts, Nancy, has lots of awesome stories and episodes about being LGBTQ and Asian American — including this favorite, about co-host Kathy Tu’s visit with family to Taiwan.

To hear Preeti’s violin performance from this episode, check out this video of her last concert.

For more about arangetrams, their history, and discussions about class and gender, Preeti recommends this primer from The Hindu and this deep look at T.M. Krishan, whose writing explores how to “de-Brahmanize” carnatic music.

For more work from Pavana Reddy (the poet who Srinidhi collaborated with onstage), visit pavanareddy.com.

Shout Outs:

Thanks to Sindhu Gnanasambandan for the conversation with L, and all the members of our community panel who gave us feedback on these stories.

Credits:

Produced by Julia Shu, Preeti Varathan, and Alex Laughlin

Edited by Cheryl Devall

Production support by James Boo

Sound engineering by Timothy Lou Ly

Theme music by Dorian Love

Music by Blue Dot Sessions and Epidemic Sound

Sound effects by Soundsnap

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

About:

Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Season 1 is presented by the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM), the Ford Foundation, and our listener community. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP.

About CAAM: CAAM (Center for Asian American Media) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to presenting stories that convey the richness and diversity of Asian American experiences to the broadest audience possible. CAAM does this by funding, producing, distributing, and exhibiting works in film, television, and digital media. For more information on CAAM, please visit www.caamedia.org. With support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, CAAM provides production funding to independent producers who make engaging Asian American works for public media.

Transcript

CATHY: Hey, this is Cathy and I need your help. It's really important for Self Evident to understand our audience and to talk about who's listening to the show with the partners and sponsors who support what we're doing. So please head over to selfevidentshow.com/participate and take an anonymous 10 question survey.

It should only take a minute or two and it'll go a long way in helping us keep the show going.

Also just so you know today's show has some four-letter words in it, and they're not beeped. Thanks.

PATRICK: I was in middle school. I helped my friend with his ,like, car detailing, car wash business. We would just go to his house and like wash his neighbor's cars and they would pay us money and then we would have money to like buy food or something.

But when my dad found out that I had spent like a Sunday afternoon washing strangers' cars, he got like so mad because he was like, "What! I didn't move here and like start this company so that you would have to be doing manual labor for, like, strange white people, you know, like how much did they even pay you? That's ridiculous, like, don't ever do that again."

CATHY: That's documentary filmmaker Patrick G. Lee. Back when he was a kid, he knew his parents had certain expectations for him. Definitely not washing cars.

PATRICK: I think my sister explained it to me because she was like, yeah, like he's built his whole sense of self on like providing for his family. For Dad to see you like working inside gig, it's sort of like hurts his pride.

CATHY: But when Patrick took the big step of finally coming out as queer to his parents, he realized he had his own set of expectations about how is Mom and Dad would react that weren't necessarily true.

PATRICK: I was expecting my dad to sort of be a really traditional Korean man about this stuff and sort of be really femme-phobic and queer phobic. And I think that's also why I expected my mom to be more understanding.

CATHY: This is Self Evident, where we challenge the narratives about where we're from, where we belong, and where we're going, by telling Asian America's stories. This season is presented by the Center for Asian American Media, and I'm your host Cathy Erway.

Today's episode is all about grappling with a change in your identity and telling the people who matter most. Later on we'll hear from a woman whose childhood was so shaped by playing violin that she wore violin earrings for an entire year, until the day she just stopped playing. And from two people who, after years of being praised for their beautiful long hair, just decided to chop it all off.

But first, let's get back to Patrick and how he saw his role in the family.

PATRICK: My older sister was actually always more the rebellious one like she had her friends over and they partied and they went to Dave Matthews Band concerts, and I'm sure they were smoking some stuff up in her room. I don't know. I definitely grew up feeling like I was a good child or like the one who got good grades and like was really into school and like sports and like did all these different things. Even just personality-wise, like listening to them more, like talking back less, right?

CATHY: Yeah.

PATRICK: I sort of felt like this pressure to continue to be the good child to my parents. If anyone should have been queer t should have been my sister because it would have just been one more thing on the list. Whereas for me it's like oh crap.

CATHY: Yeah, so they I guess they had a totally different perception of you. But do you think there were times that your parents may have suspected that you were gay?

PATRICK: I've actually talked about that with my sister and we both thought that my mom already knew, but I think after coming out I just learned like how strong the ability for parents to see what they want to see is. And in Korean, there's this phrase, it's called nunchi. It's like if you have good nunchi, then it means you're like very socially perceptive and you can sort of like navigate situations well

CATHY: Hmm

PATRICK: And it's like something that's valued right? And so even just based on that I'd be like my parents have to know. Right? Like it's part of the culture to like be aware and

CATHY: Like read through the lines…

PATRICK: Yeah, context clues. But they definitely didn't. There was a family vacation once and we were all sitting in the living room watching TV and like Anderson Cooper came on and my dad was like talking about the weather and then like sports with my brother-in-law and he sees Anderson Cooper on the TV and he's like, oh Anderson Cooper he's gay and then he goes back to talking about the sports.

It was just like a trivia fact that he wanted to like flaunt that he knew you know what I mean? Like. And I was like what? What just happened?

CATHY: So, can you describe to me the moment that you came out to your parents?

PATRICK: I marched for the first time in the Manhattan Pride Parade with this Korean drumming group.

And then I think a friend posted a photo of us. The caption had the word queer in it. And I think my mom saw that on Facebook and then like texted my sister being like, "your brother isn't gay is he?" And then my sister forwarded a screenshot of that to me and she was like, what should I say? I decided to write a letter, like a coming-out letter, in English and I asked my friend Yerim to help translate it into Korean and I emailed it to my sister so she could print it off and give it to my mom because they were supposed to have lunch the next day or something.

But by that point like maybe a couple days had passed and I hadn't reached out to my mom. So I feel like at that point her nunchi did kick in she was like, oh, I know it's coming. So she sort of like refused to open the letter or like take it was sort of like a defiant act of denial and so I was like, okay whatever.

So I just emailed it to my dad. He writes emails in English that are like very haiku-esque. They're like very short sentences that sometimes don't have any ending punctuation. My dad just emailed me back and was like, "hi Patrick. That's fine. Does anyone at church know? Make sure you eat a lot of dinner, Love Dad"

It's just like what this is so weird! Like it just ended up being that for him it was just like a negotiation right like I was gay, but it was like don't tell people at the Korean Catholic church, we grew up in and also like cut your hair. Do these other things for me and like I'll deal with this.

CATHY: Was it a relief that he said that's fine.

PATRICK: Yeah, I guess in that moment. I was like, whoa, I think my dad is choosing like family unity over airing everything out all at once.

Because I think one way in that my dad is dealing with his own mortality is just trying to prioritize family more and like family togetherness. Like I think Korean men and Korean masculinity get a bad rap.

CATHY: What do you think is the idea of Korean masculinity?

PATRICK: Yeah Korean masculinity is complex because it's like on the one hand like you're required to go to serve in the Army for two or three years and on the other hand like a lot of people look to K-pop as sort of like breaking boundaries around what masculinity can look like.

I guess for me, I was expecting my dad just sort of be a really traditional Korean man about this stuff and sort of be really Femme phobic and queer phobic. And I think that's also why I expected my mom to be more understanding. I was like, oh like my mom's the nurturing one. Like my mom will take care of me and my dad will probably be a dick about it. And it ended up sort of being the opposite.

CATHY: So, where do you think your mom is at now?

PATRICK: After I came out my mom started just like mass messaging me on KakaoTalk, which is like a Korean chat app. Questions about LGBT people or like stereotypes about us, like a negative news article about it in Korean. I think she was spiraling and her own way and she was sharing that with me.

So like I stopped reading her messages and I think they're still like 400 like unread messages in that thread.

CATHY: Wow. Yeah, that sounds like it was something that was really weighing on her.

PATRICK: My sister said that my mom was like looking and like feeling haggard almost, you know, like run down because she was worried so much about me and what it meant for me to be gay.

So I started calling my mom more regularly. Before I came out. I think the conversations I remember having with my parents were very tangible, right? It was like what I was studying or like what my job was. The markers of like success and achievement that I was working toward or doing right? And I think after I came out, the meaninglessness of those kinds of conversation sort of became really apparent because it was like there was something more pressing to deal with. And especially with my mom, she started asking me more just like basic questions of like are you happy? What are you doing that makes you happy? What is happiness for you? What does success look like to you? Like, what are you going to be doing in 20 years when I may or may not be here anymore. I guess. as my mom gets older and grapples with her own mortality, but also, trying to deal with a kid who is not at all what her expectations were for me, maybe she was also just trying to like actually get to know me better. My mom and I aren't as tight as I felt like we felt before I came out but I think there's also this understanding that I have work to do and like she has work to do and like we're both doing it.

CATHY: So in conversations about coming out, there's often a talk about like freeing yourself and revealing your true self.

Is your experience like that?

PATRICK: Yeah, like I started freelancing as a documentary filmmaker. Around the time that I came out to my parents and I think that's not a coincidence. It was like hey, I finally did that, so like what are some other areas of my life that I can be like brutally honest with myself about?

CATHY: So we heard you have a project coming up too, your own documentary?

PATRICK: It's called Unspoken. It sort of follows the stories of six queer and trans Asian Americans in New York City grappling with how and whether to come out to their immigrant parents and families. We're at a place where like as queer and trans people of color, like we literally just need more information and resources and like things for us to build community on.

CATHY: Do you wish that you would have this documentary?

PATRICK: Yeah, I definitely do there are so many books where it's like 25 successful admissions essays to the Ivy League. Like I wish there had been like 25 successful coming out letters that like queer Asians wrote to their immigrant parents.

CATHY: Patrick's documentary is called Unspoken. Later this season Patrick's going to give Self Evident listeners an exclusive way to see the film online.

So if you want to see it sign up for our newsletter at selfevidentshow.com. In the meantime, you can keep tabs on the film by heading over to facebook.com/queerAPIdoc

CATHY: When Preeti Varathan was a kid growing up in New Jersey, she took violin lessons. Not at a teacher's house or at a school, but by Skype. Her violin teacher was in Chennai, India. And as soon as school was out for the summer, she would fly across the world to spend her days studying in person. Preeti was dedicated to learning carnatic music, a South Indian tradition with Hindu roots. When she was 13, she performed her arangetram, a debut concert that hosted 300 attendees. Her cousin Srinidhi, who studied Indian classical dance, also had an extravagant arangetram.

Years later Preeti went to college with her violin of course. It sat there in her dorm untouched all year. Now looking back, she says she always meant to pick it up and play but it just never happened. Srinidhi, on the other hand, went the other direction becoming president of her colleges South Indian dance group.

So Preeti and Srinidhi are now both in their 20s and they sat down to talk about what their arangetrams mean to them now and what exactly it was that Preeti left behind. And by the way, all the music you hear in this story is from Preeti and Srinidhi's lessons and concerts.

PREETI: So I went back to our old house in Jersey last week and I was digging through all our old things now in the basement at look what I found.

SRINIDHI: Oh my gosh. It's been so long since I've actually taken a look at this.

PREETI: What are we looking at?

SRINIDHI: So this is an invitation for the arangetram which we actually hand-delivered. It's basically a rough cloth bag,

PREETI: like a pretty fancy pouch. Like the bottom is embroidered. With what looks to be intricate flowers and like gold thread.

SRINIDHI: Yeah inside of the bag is the program itself. The paper is basically woven together on the outside

PREETI: and there's a huge photo of you Srinidhi!

SRINIDHI: Also, yes, there’s a big picture of me right in the center in one of my three costumes. This particular one is orange with a magenta border.

PREETI: They look like very extravagant wedding invitations. Yeah, how do you feel looking at this like sack of gorgeous invitations and envelopes right now?

SRINIDHI: It feels really really surreal. I’m immediately, I'm like back in that space where I'm like taking pictures or up on stage dancing, but it definitely it feels very warm and homey.

PREETI: So for people who don't know, an arangetram, which actually literally translates to “to ascend the stage”.

SRINIDHI: Yes

PREETI: Is this like big debut performance. That's kind of how I always thought about it. And how frankly I explained it to like my white friends. So I did mine at 13

TAPE from Preeti’s arangetram: Guru. Friends and family...

PREETI: You did yours at 14.

SRINIDHI: Yeah

TAPE from Srinidhi’s arangetram: today’s a special occasion indeed…

PREETI: But there are people who do them at an even younger age. Like go on YouTube, you can find people who've done them at the age of like five or six. Yeah, and they take a long time. They can be like anywhere between like two and a half to, you know, four hours depending on what you're doing. And you can do them in many different types of art form.

So you dance and I played the violin but some people will play the flute and other people will sing. But the point is that they happened in this like traditional musical genre called carnatic music.

SRINIDHI: Yeah

PREETI: which is particular to South India and it's a pretty like in a way religious genre because all the songs are often odes to gods like odes to Krishna or Rama, or different Hindu gods.

And we did arangetrams and we did them back in Chennai, India.

MUSIC PLAYS

SRINIDHI: We've talked before about how it's kind of like a wedding. Especially

PREETI: it is like a wedding!

SRINIDHI: right because it's so, it's just so vibrant and detailed and extravagant.

PREETI: It requires an immense amount of work.

SRINIDHI: Yeah.

PREETI: I don't know about you but I practiced a ton.

SRINIDHI: yeah

PREETI: My summers were just completely taken over by Indian violin. I would start my day have like two to three hour lessons and practice for 2 to 3 hours and then go back and have another lesson and at some point I ended up just living under my violin teacher. And it worked. I don't know, like I always tell people that I think the act of having to really learn carnatic violin and having it culminate in an arangetram, is what taught me self-discipline.

SRINIDHI: Yeah.

PREETI: It's just like an intense amount of training. Do you remember what your summers were like in India?

SRINIDHI: Yeah. So basically I would go there, dance for you know three or four hours in the morning, come back, eat lunch, knock out because I was exhausted, and then go in the evening again, dance for another three or four hours and then eat dinner, go to sleep and do it all over again every single day for a month and a half.

PREETI: I had blisters on my fingers. Yeah, I was just so proud of the fact that I had calluses on my hands. Yeah literal blisters on my fingers.

SRINIDHI: It was so satisfying, you talked about your blisters. It's so satisfying to, like, have that -- I mean, yes, it's exhausting. Yes my feet hurt, but it's like you are just so immersed in the art form.

MUSIC PLAYS

PREETI: When you're growing and when you're in your adolescence, you’re forming all these muscles, right like people often like awkwardly walk to doors because they underestimate how tall they are or you know, your spine is getting stronger or you're just, your body is literally building from the ground up, right? And I feel like the way that I was nourishing my muscles, I was literally growing this extra limb.

SRINIDHI: Yeah

PREETI: And it was the ability to play the violin. Yeah, it felt like playing the violin was like an extra limb. People in my middle school called me violin girl and I leaned into it so much that I remember I like ordered these, really like kind of gorgeous, but also kind of glitzy gold violin earrings. They were mini violins and I wore them every single day for a year because I was like screw it, I am violin girl. And I just started to own it.

Tape: applause from performance

SRINIDHI: One of my favorite things about it is that it is something where you know, your entire family’s involved.

PREETI: It was heroic involvement on the part of our parents like

SINGING AND MUSIC from Srinidhi’s arangetram

SRINIDHI: Oh yeah. This was a, oh, wow! My mom sang for this one, that was a really really special moment for her to be there, for her to be singing.

PREETI: It’s like your way of it kind of coming out to society as this like artistic, person, but it's also a way for your family to present their involvement and the way that they've raised you.

SRINIDHI: Yeah

PREETI: Arangetrams are insanely expensive and they're by no means this like grandly accessible experience at all, like, you know within the South Indian community, it takes an enormous amount of privilege to have an arangetram to begin with. Like my dad, in more ways than one, has made it super super super clear to me that it was so important to him that me and my sister did an arangetram because he could never do one because he couldn't afford one.

SRINIDHI: It's a very privileged experience to have financially the way we did it for sure which is you know, traveling to - flying back and forth between India and the US! That is not an accessible experience to have for a lot of people.

PREETI: I just know like that that whole day the whole experience was just hugely important to my parents and I do think some of it was because of what my dad calls the hoopla, which is the money and the fact that it says something about the way he raised his kids and the fact that it says something about, like how much money he'd made and how much money his family and made and yeah that they could actually pull this event off. And you know, I think my dad sometimes says he wishes that he cared a little bit less about that. But the truth is like that was a Monumental achievement. It was something he would have never been able to do had he not come to the US.

Carnatic music, the genre which arangetram is performed in is under fire right now for being really classist. Brahmins historically have been the Gatekeepers of that musical genre and Brahmins for people who don't know are at the very top of the caste system in India and they often are the ones that get to perform it, they're often the ones that get to sort of pass these traditions down to their children. The songs are very religious, which is also why the Priestly class really gets enjoying them and there are people who are like pretty angry about how inaccessible all of Carnatic music is in India to begin with and then I think you come to the US and, because a whole host of socioeconomic factors, the way that immigration works often, like, the tech and finance workers and the people making a ton of money who come to the US are also of a certainly background and caste, you know, like our parents were by no means wealthy at all. They were very very very poor, but they were also Brahmins and I don't think that that's a coincidence.

SRINIDHI: Yeah. Yeah. I completely agree with that. The fact that they were thinking about dance, and having your daughter learn dance means that they were in the circle to potentially find a teacher in the first place. I mean there is definitely a lot of caste privilege, a lot of class privilege, which is which also makes me think I mean like yes, this definitely makes me feel more Indian, but at the same time, it's also problematic thinking about, is the fact that something so inaccessible can make someone feel so connected back to their roots.

PREETI: My understanding is that it's also sort of turning into its own industry where it's about, how do you market your arangetram such that it looks good on your common app, right? And it's about like checking boxes. And I know for a fact that like I put this thing on my college application because I was like “Hey. I worked hours on this, and also, what else is going on here, man. I didn’t do that much else. I did eventually join swim team. Just for people listening.

SRINIDHI: In college I was part of a South Asian Fusion dance team Bryn Mawr Mayuri.

PREETI: She was the president of it. Don’t sell yourself short Srinidhi!

SRINIDHI: Which was which was a really cool experience.

PREETI: You still dance and it's a huge part of your life

TAPE of Srinidhi’s last performance: Where does the heart go, when it is ripped from the motherland

SRINIDHI: Last year a couple of friends and I, we did a poetry music and dance collaboration with a South Asian poet who's based in Los Angeles named Pavana Reddy. We created this performance about the immigrant experience. So, sort of connecting that back to something that means a lot to me, my family --

TAPE of Srinidhi’s last performance: She handed me her own, and said, “Whatever you…”

SRINIDI: I feel like dance has always been something that connected me back to myself and sort of knowing... having this very intuitive sense of my body is a very grounding thing. I mean, we've talked about it. I have a full-time job. It's not something I do every single day or every single week or even every single month, but it's still something that I wish I did more because there's just a trust in my body and in myself that I feel when I dance.

PREETI: It's just so funny that you say that Srinidhi because to me you are the gold standard for the kid that did the like Indian classical art form, got trained and then as an adult still does it. Like I'll talk to aunties and uncles and they'll be like, it's a gift. You should do it. You shouldn’t let it go. You know who they're thinking of? They’re thinking of Srinidhi. Srinidhi’s the gold standard.

SRINIDHI: Oh well, thank you for saying that.

PREETI: So I wanted to play this clip for you.

VIOLIN MUSIC from Srinidi’s last performance in high school

PREETI: It's the last performance I did in high school. I was 17 years old and it's actually the last time I played. I always dreamed of playing in New York and I was finally on stage and this beautiful concert hall.

VIOLIN MUSIC FINISHES

SRINIDHI: So what's the reason that you actually stopped playing the violin?

PREETI: I don't know. It's sort of... I think it's sort of complicated and I've kind of thought about this a lot. Indian carnatic violin was the biggest thing happening in my life until the age of 18. And it actually did bring me a lot of joy. But there's also a degree to which playing the violin wasn't entirely my choice, and I think when I went to college it was the first time I was away from my parents.

SRINIDHI: Yeah

PREETI: It was the first time where I really had the freedom to set my own identity. It was the first time when I didn't necessarily need to be thought of as violin girl. Honestly it was a surprise to me when I got to college. I brought my violin to college every single year, except my senior year. I’d brought it even though I never touched it. It was like my body was like this year will be the year that I like play at university.

And I just didn't and the year would end and I would still have not touched it. Maybe I wanted to try something different. Maybe I wanted to be someone different but I think how I feel about it is…. I guess so complicated, for lack of a better way to put it. It's like, I was literally down in Florida visiting my parents a couple weeks ago.

And of course like as usually some aunties and uncles were over for tea, and they were like, “We've seen your arangetram video.” Which like already seems so funny to me because... my God, that was so long ago. Like why are you looking at a video of me at 13? But it's just such a point of Pride for everyone, especially my dad. To him, me playing the violin and being able to execute on something like that is still one of my greatest accomplishments and it feels so weird to have cut the strings on something that's supposed to be a big part of who I am. I guess I worry sometimes that by pulling away from that tradition, I've let the people who invested so much time and me down.

SRINIDHI: So have you talked to your dad about how you feel?

PREETI: For a long time I didn't but a couple weeks ago, I picked up the phone, and I was like “Hey, Dad…”

PREETI: Hello. Can you hear me properly?

PREETI’S DAD: Yeah.

PREETI: Okay. So like at what point did you decide that you wanted me to either do a musical art form or do an arangetram?

PREETI’S DAD: Art form we are planned even before you were born. Kids should have some sort of art form experience. So that is already kind of decided but we didn't decide whether you're going to play violin piano or whatever it is. The music has given you a lot of values it to what is good, and what is the right thing to do. Put it that way.

PREETI: What about culturally? Do you think it made us culturally more Indian?

PREETI’S DAD: Culturally, more Indian not necessarily, but I think it does help you to appreciate - see, you don't have to follow very specific things in a particular culture in order to show appreciation of the culture.

PREETI: Do you ever regret the amount of time and energy took on your behalf?

PREETI’S DAD: Absolutely not. I am glad, very happy that the time I spent and invested - mommy also spent a lot of time in this - why should I regret? There is no reason. I'm very happy that I spent so much of time.

PREETI: What’s interesting is that I've basically stopped playing after I went to college. Is that something that, you know, bothers you or…

PREETI’S DAD: No, it doesn't bother me. There are other priorities. If you feel that you want to do something different, the key thing is acquiring ability to do certain things at a young age. It helps you to develop your brain in such a way that you become one of the really smart person as you grow.

The priorities change. Maybe in another 5-10 years, you may feel that, “Oh, I want to play violin.” You may pick up the violent and then start playing regularly and then it's fine because at that time you may find time and then you want to, but whatever you learnt is there.

PREETI: The first time like we really talk through this, like I cried. I started crying because I think I just never expected my dad to let me off the hook, in a weird way.

SRINIDHI: I think that's really really fantastic that he thinks about it that way because he gave you all of this entire experience and you know you related to it in one way back then but it also shows that you can sort of take it from here.

PREETI: I don't know. I think it made me realize that I got what I needed from it, you know? Maybe in talking about letting go of something or losing something like I'm doing a disservice to myself because the literal language of loss invokes pain, but I'm starting to think that's not really how to think about it. It's like, I didn't give up my roots. I don't feel less Indian because I don't play the violin anymore like. I think I just evolved into a different person with, like, different desires and different values and different priorities.

SRINIDHI: Yeah at the end of the day, it's far more about evolving than it is just about giving something up.

PREETI: And maybe this whole thing is just a fantasy, but I'd like to think, one day I will pull out my violin and I will tune it.

VIOLIN MUSIC

PREETI: ….and I will start playing again and I will play sankarabharanam because it brings me joy and makes me happy. But I won't have to be violin girl.

CATHY: Changing your relationship with something you identified so so strongly with as a kid and with all these deep cultural roots -- that's one kind of transformation. Sometimes though, the thing you're changing is physical as well. Like a haircut.

VIOLIN MUSIC FINISHES

MUSIC PLAYS

Our last conversation comes in two parts starting with this essay from L, a Korean-American genderqueer writer who lives in Philadelphia. We love the story L had to share so we had them read it out loud. L read this was while visiting their hometown of Chicago during the summer. So that buzzing sound you might hear is the sound of cicadas at dusk.

L: I want to start six years ago, back when I had a mane of lustrous black hair, and I want to tell you about my hairdresser at the time: Tina.

Tina was an older Korean woman, an ajumma, who I couldn't talk with much because she didn't speak much English and I was part of a generation that had forgotten our Korean. Which turned out to be less of a problem than you'd expect because Tina knew how to cut Korean hair and she knew what was right for your hair and she was going to cut it that way kind of regardless of what you had to say about it. She ruled your head with the authority of a grandmother.

Tina and I tended to have the same conversation each time I was in the barber's chair. I would say, “Tina, I want two inches off this time.” And she would reply, “One inch?” “No Tina, two inches!” “One inch.” And so I'd have to reply. “Okay, Tina. One inch.”

Sometimes Tina would ask, “Why do you want to cut your hair?” Sometimes she would tell me going any shorter wouldn't look any good.

Why did I want to cut my hair? It was long, healthy, beautiful, but I had spent enough mornings in front of the bathroom mirror carefully rearranging my hair, laying it against my cheeks to give the appearance of a thinner face or slicking it back for an illusion of sleeker features.

I looked at all kinds of tutorials for braids and easy waves and contemplated getting or not getting bangs. It seems like with just the right manipulation my hair could transform this chubby moon-faced Korean face I had been taught to hate, into someone who is gorgeous. And even when I was young, I think I had the wisdom to recognize that in carrying this promise, my hair carried lies, and the only way to be free of them was to cut it off.

Tina was the first partnership I would leave because I realized that I wanted something from her that she wasn't willing to give, and so I made the gutsy move to the other side of the hair salon to a younger Korean man named Mr. Rhee. Mr. Rhee, it turned out, spoke even less English. During our first appointment I just said I want it short and tasked him with carving a new me out of my long straight strands. Although Mr. Rhee and I never talked much, I always felt a particular kinship with him. Every time I sat in his chair, I felt that I was entrusting him with something important to me. Communicating an otherwise inexpressible self-image to the world that made me feel real, consolidated. And although I could have never communicated all of this to him with a language that was lost between us, somehow after he was done, I would look at myself in the mirror and be reassured that somewhere in the mess of my hair, he saw me how I inexpressibly saw myself. Looking at his finished work, Mr. Rhee would laconically describe it “strong”.

When I moved to years ago, I ended my partnership with Mr. Rhee and I found another hair cutter and Philadelphia's Chinatown, an older Chinese woman named Ying who cut hair beautifully, and although I came to her with the pixie, once again I felt I wanted to go shorter. “Can you take off an inch?” I'd ask her. “Half an inch,” she'd reply. “I want it to be shorter.” “No, you need length. You are a girl after all,” she'd say as she tenderly brushed her fingertips through my hair.

I almost told her in frustration that I wanted a man's haircut. I wanted to look like a boy, but I kept my mouth shut. In the gentle yet firm tone Ying took on, I felt that in me she saw a daughter and that was all it took for me to be scared of disappointing her. Six months ago, I sat in Ying’s chair and told her to buzz my head. She didn't want to. She asked me if I was sure. I told her I was. She set to it.

SOUND OF BUZZING HAIR CLIPPERS

I've since stopped going to hairdressers.

MUSIC PLAYS

The hair I have now is so simple that I buzz my own head every two weeks, but it has never looked quite as beautiful as when Ying buzzed it that first time. I left her Salon with a little mark of her care on the back of my neck -- the hairline buzzed and the shape of the edges of a lotus petal.

CATHY: So after L sent us this essay, they thought of Sindhu, an old college friend.

SINDHU: Hey L, how's it going?

L: Hi Sindhu!

CATHY: It turns out that while L was negotiating with hairdressers and getting that lotus flower buzz cut, Sindhu was having her own transformation. After college, she was burnt out and had some big existential questions to think about. So Sindhu decided to go live at Green Gulch, a zen farm and meditation center, where she also buzzed her hair. It was such a random coincidence that the two friends reconnected and decided to catch up.

SINDHU: I think I got a message from you and you were just like, “You buzzed your hair? I did too!” Or something like that. I just love that you remembered me and like wanted to reach out to me and share with me that moment in your life, which is like, a personal, fragile one. I remember reading the buzz line and just being like yes, someone I can talk to about this, because hair’s a weird thing, you know, it seems like it shouldn't matter, like it's just it's just dead matter, and yet you know, every decision that's made has weight.

L: When I did it, I felt like it was so much like of an of act of anger and rebellion. I had refused to take a makeup exam for medical school, which I had been told I would have to complete in order to leave to take a break. And I didn't for various reasons. And so I like buzzed my head and I was like, I'm free. No one can touch me now.

SINDHU: That's beautiful. I also had this long thick black hair and it was always like the first or second thing when I was, met someone new or like re-met a relative it was like

“Wow, your hair!” you know? Yeah. I didn't realize how much that was a part of my identity until cutting it off.

A good chunk of how I saw myself with somehow this hair because it felt like that's, it was a good chunk of how other people saw me.

L: Yeah, we share this experience. Like I'm just thinking about that like family moment how it's like the second or third person someone comments about you is your hair.

It's weird. I experienced those moments more so like when I was younger. It's this realization that you're like, my hair carries so much, like apparently it means so much to people but I don't feel in control of that eaning at all.

SINDHU: There was just a period of time where I'd like, every time I walk into a bathroom and look in the mirror, I’d sort of like hold my hair up and hold it back and just like look at myself and be like, oh, I don't know why it just feels like this doesn't belong here.

I was also living in a monastery, so the whole like monk thing was definitely in the air. And my boyfriend, I mean he always loved my long hair, but he was visiting and I'm like look mister, I’m gonna get it shaved and you're coming with me. We're eating lunch and I saw Happy Cuts like across from us and I was like, we are going there afterwards and you're going to watch me shave my head.

L: Wait was this like spontaneous or were you like internally planning? Like we're gonna go get lunch and I'm going to point to the Happy Cuts across the street.

SINDHU: No, it was, it was... I don't think anyone plans on Happy Cuts. No. Yeah, the Happy Cuts people too, I mean, different story than your Korean hairdresser, but they too were like, are you sure can we do it in steps for you? And I'm like no buzz it.

L: It's funny because I decided to buzz my head during a really isolated time in my life, and I'm kind of interested because you buzzed your head during a time when you were in a monastery and I don't assume that another individual with a buzzed head is genderqueer, that's like a bit much but I feel a little kinship with them about being in that space beyond conception.

SINDHU: Just like the way that you’re responded to and like every choice to do something that's like pushing against all of that is kind of like the sort of magical thing.

It's like, why would you do that?

L: I think that like the queerness that I was mostly exposed to in college was white gay men. Which I think tends to be the dominant queer narrative. And so I would like kind of have conversations about how I was questioning and I was like “Am I gay?” and the reactions would be “If you were gay you would know.” That's like one really specific manifestation of queerness like the most legitimate gay or the gay that I feel like our society is weirdly really comfortable with promoting as a narrative is the person who was gay since birth.

There's something about a lack of movement between categories that we seem to like. Straight from birth, gay from birth. I was born this way. Whereas like gender fluidity is like a concept that I didn't really encounter that much. I think the origin especially of the buzzed head is, I decided to move into a semi-communal queer person of color house and when I moved in there was a person there and they had been living in the house for a long time. So they were older than me and most importantly their hair was buzzed and bleached. They looked fucking amazing. When we met we introduced ourselves. We introduced our pronouns. I was not using they at that time. And they used they. There is something about the way that they inhabited their body regardless of like the medicalized ways that we've been taught to think about bodies. All of those biological concepts seem like laughably irrelevant.

MUSIC STARTS

It's like literally they are so powerful that when they walk into a room it flies out of your head. It's almost like a rose colored image. It almost feels like a love story because it was a moment of recognition. It was suddenly someone that it felt like oh, this is who I've been searching to be.

SINDHU: Wow. I'm crying. I'm glad that we did this.

CATHY: Next time on Self Evident: It's been three years since the Trump Administration reversed course on how the US treats refugees seeking Asylum. We'll investigate what this campaign of detention and deportation has done to Americans caught in a cycle of displacement.

This week’s episode was produced by Julia Shu, Preeti Varathan, and Alex Laughlin. We were edited by Cheryl Devall and mixed by Timothy Lou Ly. With production support from James Boo.

Our theme music is by Dorian Love.

Thanks to Sindhu Gnanasambandan for that call with L, and all the members of our community panel who gave us feedback on these stories.

And a very special thank you to Nikita Miller, and the 1,004 crowdfund backers whose support made this episode possible.

We’re linking to a youtube video of Preeti’s final concert at the Asia Society in New York, back when she was a teenager. It’s an amazing performance. And a reminder to sign up for our email newsletter, at self evident show dot com, for a special link to watch Patrick’s documentary “Unspoken.”

ALT: And don’t forget to check out our show notes to learn more about Preeti, Patrick, and L.

CATHY: We want to hear from you! Let us know what you thought about this episode on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, @selfevidentshow. Or e-mail your thoughts directly to community@selfevidentshow.com.

CATHY: Self Evident is a Studiotobe Production. This season is presented by the Center for Asian American Media, with support from the Ford Foundation, and you! Our listeners. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP.

CATHY: We’re managed by James Boo and Talisa Chang. Our Senior Producer is Julia Shu. Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda. Our Audience Team is Blair Matsuura, Joy Sampoonachot, Justine Lee, and Kira Wisniewski.

CATHY: I’m Cathy Erway. Let’s talk soon! And till then, keep on sharing Asian America’s stories.