Episode 028: Heartbeats

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

The Covid-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of caregiving work — and the ways that this work is overlooked, under-resourced, or placed as a burden on families without a sense of fairness or compassion. In this episode we’re sharing two stories that show people taking on the role of caregiver, and asking: Who gets to be healthy in a world that leaves so many people with family as their only lifeline?

“My Heartbeats”: When Indian American filmmaker Tanmaya Shekhar moved his life from Kanpur to New York City, he was running away from family and dreaming of standing on his own two feet. But when the first wave of Covid in India put both of his parents in the hospital, he found himself in a race against time to reunite with them — and then a slow process of rethinking his life’s path, as an immigrant and as a son.

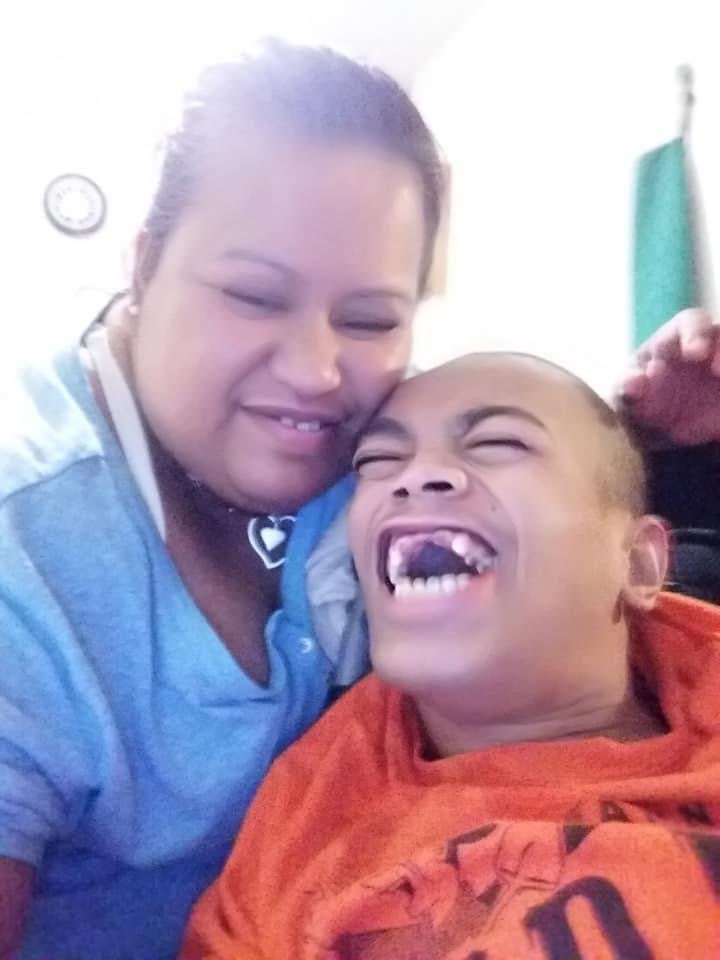

“Delma and Delvin”: Guest contributor Angela Edward shares a day in the life of her aunt Delma, a middle-aged Micronesian mom whose full time job is taking care of Delvin — her 30-year old son who has always lived with cerebral palsy. After being hospitalized for Covid, Delma invites Angela over to spend time with Delvin and share how it feels to be senselessly locked out of the American healthcare system.

Resources, Reading, Viewing, and Listening:

LISTEN: For Micronesians by Micronesians podcast

READ: “How Decades of Advocacy Helped Restore Medicaid Access to Micronesian Migrants” and “Hirono Seeks to Restore federal Benefits for Pacific Islanders from COFA Nations,” by Anita Hofschneider for Honolulu Civil Beat

READ: “A Historical and Contemporary Review of the Contextualization and Social Determinants of Health of Micronesian Migrants in the United States” by Davis Rehuher, Earl S. Hishinuma, Deborah A. Goebert,and Neal A. Palafox for the Hawai’i Journal of Health & Social Welfare

READ: The Husk, a newsletter covering Micronesian people and happenings

WATCH: “Reflections at 29,” a documentary short by Tanmaya Shekhar about the costs and regret of living as an immigrant filmmaker in the U.S.

SUPPORT: Donate to the Hemkunt Foundation, which has been helping Indians survive, recover from, and weather the impact of Covid-19

Credits:

Produced by James Boo, Emily Cardinali, and Angela Edward

Edited by Julia Shu

Fact checked by Tiffany Bui and Harsha Nahata

Sound mix by Timothy Lou Ly

Self Evident theme music by Dorian Love

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

Self Evident is a Studio To Be production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts creator program — and our listener community.

Transcript

Pre-Roll: Listener Survey

JAMES VO: Hey everyone, this is James, the showrunner at Self Evident, and I’m just stopping by to say — If you haven’t filled out our annual listener survey yet, it would be a huge help if you could do that before starting today’s episode, by going to selfevidentshow.com/participate.

JAMES VO: The survey’s anonymous, it takes just a few minutes, and it really helps our team understand where you’re coming from, what we can do for you, and how to move the whole show forward.

JAMES VO: Also, if you take the survey, you also have a chance to win a $25 gift card to an Asian American owned-business that we’re fans of.

JAMES VO: So, take the survey at selfevidentshow.com/participate.

JAMES VO: We will also leave a link to it in the show notes. And thanks for listening!

Cold Open

Tanmaya Shekhar: She said, we've booked your hotel. So the car will take you to a hotel, go there.

TS: Uh, I made some food, eat some food, go to the hotel, take a shower. And then you can go to the hospital.

TS: I said, no, I need to go to the hospital now.

TS: She said, no, no, no. I made some food for you with the food will get cold.

MUSIC begins

CATHY VO: That’s Tanmaya Shekhar, an Indian American filmmaker based in Brooklyn. In mid August of 2020, he was in the backseat of a taxi that his aunt had hired to pick him up at the airport in Ranchi, in northeast India.

CATHY VO: Both of his parents were hospitalized with COVID, and he was desperate to see them and do something to help them.

CATHY VO: But after almost a full day of flying from New York and overcoming pandemic restrictions, Tanmaya found himself pushing against an unforeseen obstacle – the rapidly cooling food his aunt and uncle expected him to eat.

TS: And my uncle, he calls me, he said, “I told the driver to go to the hotel.”

TS: He's like, "The food is waiting for you. The food will get cold."

TS: I was like, what's up with this food? I mean, it's like, I need to see that my father is alive.

TS: I told the driver, I was like, go to the hospital. He said, no, no, no, "Sir, said take you to the hotel."

TS: The stakes could not be higher and still they're like, “No, hot food is more important.”

MUSIC ends

TS: I was like, "What if I'm eating hot food, and then my father passes away? Like, that's the last thing I remember that — when my father passed away, I was eating, like, hot food."

TS: Like — I don't know, it was just like, I was just going crazy. And then I, at least I took the driver's phone.

TS: I called the doctor. The doctor said that “he's still not very good, but, you know, it's not life-threatening right now…”

TS: I was like, okay, fine.

MUSIC: Theme music begins

TS: Tanmaya Shekhar: And he said, "I'm free at 2:00 PM. So come, come meet me at the hospital at 2:00 PM."

TS: Okay. Now I can go to the hotel and now I can take a shower and I can eat hot food.

Open

CATHY VO: This is Self Evident, where we tell Asian America's stories to go beyond being seen.

CATHY VO: It’s been two years since the COVID pandemic upended so many parts of our lives. And this month, we’ve again been reminded how isolating it can be to take care of the people we love.

CATHY VO: So today, we’re sharing two stories of people becoming caregivers.

CATHY VO: One of those stories is Tanmaya’s frantic journey back to northeast India to take care of his parents. The other follows a Micronesian mom in Midwestern America — who’s always been the primary caregiver for her son, who has cerebral palsy.

CATHY VO: Both were affected by COVID, and both have used every resource available to keep their family healthy.

CATHY VO: And these stories raise a lot of questions about who gets those resources, who gets to be healthy — in systems that leave so many people with family as their only lifeline.

MUSIC: Theme music ends

Segment 1: My Heartbeats

CATHY VO: Before the pandemic, Tanmaya actually spent years keeping his distance from the family.

CATHY VO: He grew up in the north Indian city of Kanpur .

CATHY VO: And like his dad, Tanmaya came to the U.S. as a young man, looking for opportunity.

CATHY VO: But as immigrants, they were on very different paths.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya’s dad was actually already married when he came to the States for grad school. And he didn’t want to stick around.

TS: Both him and his mother, for both of them, like family was the most important thing in the world, so they were both very clear that they didn't want to live in the U.S., even though my dad had, like, a job opportunity — options in Silicon Valley.

TS: So he came back to India to become a professor in university…

CATHY VO: Tanmaya, on the other hand, moved his entire life to New York City after going to school in India.

CATHY VO: He called himself “Tanmaya 2.0” and embraced his new life as a hustling indie filmmaker, making it on his own in New York City .

CATHY VO: For him, the whole point of immigrating was to break away from the rest of his family. Especially his dad.

TS: So I would say I had a very complicated relationship with my father. He was a classic, at least Indian father archetype, like, you know, his emotional range wasn't very big.

TS: And there's always like a hierarchy in Indian families. So, you know, he's always like my father and I have to listen to him and I wasn't the type who pushed back. And then I would feel resentful.

CATHY VO: And growing up in a house that was constantly crowded with family members and family friends got Tanmaya dreaming of a life where nobody would be looking over his shoulder.

TS: It's like a very classic, like, middle-class Indian family where everybody's very overbearing and everybody's like very involved in what everybody else is doing.

TS: So it was just, it was a lot. Like, my grandmother is a sort of person who would be like:

TS: “Oh, so Tanmaya, you woke up at 10 in the morning and it's 9 PM right now. And the last 13 hours I saw you study for only two hours…

TS: And then you were out in the evening for four hours. Like, what were you doing the rest of the day?”

TS: You know, that's how my grandmother is. She was a keeper of time.

TS: And so anyway, I think by the time I graduated, I was just like, ready to, like, run away. And so I think my living in the U.S. was… I just felt so happy.

TS: I was like, this is great. You know, I can be out at 4:00 AM and nobody's keeping track of, like, what I'm doing. So I think, I, I think I just felt very free and I was, yeah, I was, I was like, this is great. I think I can live here forever.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya’s dad, Dr. Rajiv Shekhar, is a director at I.I.T. Dhanbad, or the Indian Institute of Technology in Dhanbad .

CATHY VO: After the pandemic started, the university put in really strict lockdown rules , and Tanmaya's dad felt pretty safe. But then in mid-August of 2020, he started showing serious COVID symptoms.

TS: My father had been sick. Like he had very high fever and it had been like four or five days.

CATHY VO: Things got so bad that the local doctor gave him a CT scan, and said he needed to transfer to a hospital with ventilators.

CATHY VO: But the nearest hospital with ventilators was a five hour drive away .

TS: I saw this WhatsApp video. It was a video that my father recorded in the ambulance as he was being taken away.

Rajiv Shekhar: My first trip in an ambulance lying strapped to my feet with an oxygen mask in place…

TS: He recorded this one minute video talking about, like, how great he is and how technology has become amazing...

RS: They only use needles now to insert the plastic tube, and then they withdraw the needle.

TS: Just seeing him within an oxygen mask and in an ambulance was like, it made me feel terrible. But, like, his one minute long video where he kept saying that he was fine…

RS: Must be looking very unsettling, but actually I'm very comfortable.

RS: So I am fine... I'll be back soon... Don't worry at all.

TS: It was also, like, he'd become delusional and he had lost his mind...

TS: I was crying.

TS: And then I called my sister and she was like, “What happened?”

TS: And then I said, “Did you just see WhatsApp? Did you see?”

TS: And then she opened her WhatsApp and then she saw it. And then both of us were, like, crying.

CATHY VO: By that time, it was 4:00 a.m. in New York.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya started thinking about how he could get to India to help out, but his family members were all saying the same thing:

TS: “It just feels like there's nothing you can do, so you should probably just stay there.”

Cathy: So what convinced you to finally go, then?

TS: My mother, my God, uh, my mother had created a WhatsApp thread just between me, her and my sister Tushita.

TS: And she had…

TS: …she called this WhatsApp thread, "My heartbeats."

TS: So I woke up to see this new WhatsApp thread. It was called "my heartbeats."

TS: And — (Tanmaya gets choked up)

TS: — and I think…

TS: …I think this is when my mother had started to panic because now, uh, when they had, When the doctor had told my father to go to the hospital, you know, the COVID test still hadn't come back, but now he tested positive for COVID.

TS: And like his situation was deteriorating by the hour.

TS: And she had also turned positive, and her oxygen levels were also going down and she also had started having a fever.

TS: My mother usually tries to be very calm, but when she sent this, like, “My heartbeats”, like, it was almost…

TS: It felt like, yeah, that's when I was like, “I think this is bad and I have to go.”

CATHY VO: Tanmaya had actually caught COVID himself in March of 2020.

CATHY VO: He was hoping he still had some level of immunity from that. Also, he’d been pretty isolated at a relative’s house for a few weeks.

CATHY VO: So he took the required COVID test for travel, then went to the airport to try and get to New Delhi .

CATHY VO: But at the time, India was closed to most international travel , and Tanmaya didn’t have an Indian passport anymore. So at first, the airline didn't want to let him board the plane, knowing he probably wouldn’t be allowed into the country.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya went back and forth with them, saying he had to get to his dad.

TS: And then I just, I, I started crying and I just told them that just let me go.

TS: If they don't let me in the immigration in India, then you know, I just come back. You know, I just come back.

CATHY VO: Stubbornness paid off, and Tanmaya got on the plane. Then, he spent the next 15 or so hours turning over every possibility in his head.

CATHY VO: What would happen to his father? Would he have to move back to India to take care of his family?

CATHY VO: Could he even do that? He felt like he could barely take care of himself.

CATHY VO: But once Tanmaya paid for the plane wifi and started calling up his extended family members in India, he realized he wasn’t doing this on his own.

TS: The one thing which I know about India is that connections go very, very, very, very, very far.

TS: I just started calling my cousins. I said, “Oh, do we know somebody who works in immigrations and customs?”

TS: I also got in touch with, like, another uncle, one of my mother's cousins. I called him up.

TS: I said, my father is not really well. And I don't know what the rules are, but I really, really need to enter.

TS: He said, "Don't worry Tanmaya. You will be able to enter.”

TS: Honestly, the family and friends network in India is pretty awesome. It's like, when you say that there's something with your family, like everybody rallies together.

CATHY VO: When Tanmaya got off the plane, he was very quickly put in a line for people without the right paperwork. He was about to be put in a hotel for two weeks of quarantine – or sent right back to the U.S.

CATHY VO: On his phone, he was frantically texting a man his uncle had told him to contact.

TS: “If you aren't here in the next five minutes, then I'll be shipped somewhere, and then there's no coming back."

TS: So this guy, he came, and finally, he extracted me from that line.

TS: He said something something something…

TS: He's a miracle worker, but he was just, you know, he was, uh, just a guy.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya finally made it to the right checkpoint and presented his negative COVID test.

TS: It's fine. And that's it. Finally, I've made it. It's in. That's it.

TS: I'm in India right now.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya had one more flight from New Delhi to Ranchi , where his parents were hospitalized.

CATHY VO: He made it to Ranchi, but before he could get to the hospital, of course, there was the showdown over hot food with his aunt and uncle.

TS: And he was like, "The food is waiting for you! Your aunt made it with her hands! It'll get cold!"

SOUND: The word “cold” echoes and fades away

CATHY VO: When Tanmaya — fed and showered — got to the hospital that afternoon, the doctor said his dad had only five percent of his lung capacity left… with only a five or ten percent chance of survival. He’d been receiving oxygen, and had been put on a ventilator.

CATHY VO: The only other thing to try was something called convalescent plasma therapy — that’s a transfusion of plasma from a person with a matching blood type, who recently had COVID, and had a strong antibody response.

CATHY VO: So Tanmaya started looking for donors who met the requirements.

TS: And for that, it was just like an insane outreach effort.

TS: Facebook and Twitter, my cousins, and my sister, older relatives put out ads on the local newspaper and radio, and my father's university...

TS: They had, like, a grassroots, like, on the ground approach where they were just like knocking on doors.

TS: Like, within three hours, like a thousand people in the world had my phone number now. And I am just inundated with calls and texts.

TS: Whenever celebs are interviewed about, like, “Oh, what was the moment when you decided that you wanted to be a tennis player? Or what, what was the moment when you decided to be a fine artist?” And they always have a story…

TS: They have a story — "Oh, you know, when I was seven years old and I saw this film and it really inspired me and it changed my world."

TS: I've taken a lot of extreme decisions.

TS: Like I've moved countries, I've started a new career. Like, I switched from economics to filmmaking, it was always like a series of events...

TS: But this afternoon was definitely like one moment when I think I'm getting texts from all these people, from people who are older than me and defying the hierarchy, which exists in our family.

TS: It's like my uncles and aunts, and even, like, one of my grandmother's sister is calling me and they're asking me: How can they help?

TS: And... (breathes out deeply)

TS: That afternoon, I felt like, okay, I am the person in charge of my family. It's not my father. It's not my mother. It's not even my mother's sister or my father's brother. It's me.

TS: Like, I am the person in charge of my family.

CATHY VO: Throughout it all, Tanmaya was going back and forth between the private hospital where his dad was, and a public hospital where the blood bank was located, checking for donations.

CATHY VO: His dad, as a well-known director for a major university, was getting the best possible care. But when Tanmaya showed up to the blood bank, he realized that conditions in the public hospital were much, much worse.

TS: There's thousands of people. And at night, what happens is that every inch of floor space is covered by people who were sleeping on the ground.

Cathay: Oh, my gosh.

TS: I think that's when you kind of come to terms with, like, the poverty in India, it's just, because it was a public hospital it catered to, you know, people who are struggling more in life, financially, people who are poor and it was just…

TS: Yeah, that hospital, it just smells of death. It's literally, like, death and despair.

TS: I kept thinking about it myself. Like if I, if somebody had asked me to donate blood plasma, like would I donate to them?

TS: Because in the blood bank, you know, where people are supposed to donate plasma, they're sitting on this chair, which has a white sheet on it, but the sheet has bloodstains on it.

Cathy: Ohhhh…

TS: And the needle, which…

TS: They're plugging you onto a machine, and one end of the machine is a needle, which goes into your arm. And the noodle is connected through a tube to the machine. And the tube is always on the ground. So they just pick something off the ground and then they just put it into somebody's arm.

TS: That was (breathes deeply) — that was really, really hard because I kept thinking of somebody, I'm asking all these people to donate plasma, to save my father's life.

TS: But if somebody asked me to donate plasma, right now, in that moment, even the person who has donated plasma for my father, if that person asks me to donate plasma for somebody else in their family…

TS: I wasn't sure if I could do it because I was like, this is… you would get sick, you know?

TS: I mean, sick is the least. Like, you could die.

CATHY VO: At the same time, Tanmaya was realizing that almost all the people who had answered his call for donations to save his father, people potentially risking their own health — were from a lower class.

CATHY VO: The wealthier people he had asked weren’t showing up.

CATHY VO: It was a sobering reality that stuck with Tanmaya when he finally headed back to his dad with the plasma he needed.

CATHY VO: He was exhausted.

TS: And that's when my phone rings. And I see a call from my father. And this is the first time that I'm seeing a call from him once I've landed from India. And I haven't heard anything from him, no texts, no calls.

TS: So I picked up the phone and this is like, yeah, I think this is a conversation, which I'll probably never, ever, ever, ever forget.

TS: I heard like some wind (makes a hissing sound)

TS: I was in the car, the window was open, and I thought it was the wind.

TS: So I rolled up the window, but I'm still hearing this wind. And I think it's like some bad connection or this (makes a hissing sound)...

TS: It takes me a really long time to figure out that that's actually my father’s voice

Cathy: OH, my gosh, wow.

TS: Um, because it's, his lungs have gotten so bad that he can't, he can't speak.

TS: There's no words, like his lungs don't have the power to say words.

Cathy: Mhm.

TS: And so he thinks that he's speaking. I don't know what he knows about his condition, but, He's probably trying to speak but all that, it's coming out as wind.

TS: And I… (breathes deeply)

TS: …I was just like,” Papa, you don't have to say anything, I'm coming with blood plasma, I found something. The doctors will put it into you. You're going to feel better, in a few days you're going to be out of the hospital.

TS: It's all going to be fine. It's fine. I'm here. I'm around. Don't worry.”

CATHY VO: Ultimately, through his outreach, Tanmaya's parents both received donated plasma, and recovered enough to be discharged.

CATHY VO: It’s hard to say how much the plasma cured his dad, compared with all the other life-saving treatments. The doctor told Tanmaya his father’s recovery was a miracle.

MUSIC: A slightly melancholy, midtempo, guitar-driven pop tune begins

CATHY VO: But the recovery was really just beginning.

TS: So yeah, so they were in the hospital for more than a month. And on September 17th, we were back in Ranchi now and now begins the long term healing process.

TS: Now it's like, you know, the life-threatening stuff is over, the thing because of which we were panicking and blood and plasma, and maybe we’d lose their life…

TS: …and then began this, like, slow recovery process.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya stayed to help. He would measure out and distribute medication, pay close attention to both parents' healing and help out wherever else needed.

CATHY VO: Over the next three months, Tanmaya spent more time with his parents than he ever had in the past few years — especially with his dad.

CATHY VO: He remembered a moment from before the pandemic that felt like it came from a totally different life.

TS: Just before the pandemic in January, 2020, I had an endoscopy and it's an anesthesia thing .

TS: So it's like when you go to the hospital, uh, they'll only check you out if you have somebody to accompany you...

TS: And, um, my really good friend Fidel, who I usually rely on was out of town.

TS: So I'd ask the doctor, like, you know, “If I wait at the hospital long enough, can I just check myself out?

TS: My, can I just go out by myself if I don't have anybody?”

TS: And the doctor said, “Yeah, that's fine. It'll be fine.”

TS: And so I had felt kind of proud. I was like, you know, “I'm so independent. I can, I can have a procedure and I have anesthesia and I can walk out by myself, I don't need anybody.”

MUSIC: Slightly melancholy tune ends on a light, reverberating beat

TS: But when this thing with my father happened, I mean, I was just like, so blown away, because...

TS: like he's helped so many people, like...

TS: in our house when we were growing up, his parents were not well, he took them in. My mother's nephews wanted to live with us, so he took them in.

TS: There was always a rotating cast of people from our ancestral village who had moved to the city, looking for jobs.

TS: And so like, you know, in our three bedroom, small three-bedroom house, we had like 14 to 16 people living, you know, at different points of time.

TS: And just...

TS: He had helped so many — like his students, his university students — and he had helped so many people, that when he was in the hospital, like over the next few weeks, thousands of people called me, thousands of people called me.

TS: Friends, students, parents of students, alumni, checking in on him like regularly, “How's he doing now?”

TS: I think it was, like, an eye-opener. I was like, what am I doing? I grew up in India, I'm ,like, trying to make my life in a new country where I have my independence. Nobody's micromanaging me.

TS: But if something happens to me, I just go to the hospital by myself and I have to check myself out.

MUSIC: A dreamlike piano tune begins

TS: Whereas with my father, like it's like a whole army of people.

TS: Everybody's there for you.

TS: So...

TS: I stewed in that thought forever, I was like...

TS: That definitely made me think that the way I'm living my life now is not sustainable, and I was like, I think I want to make some lifestyle changes.

CATHY VO: Tanmaya and his dad started rebuilding their relationship.

CATHY VO: The experience of stepping up to take care of his family, the feeling of their community backing him up in a crisis, the reality check of seeing the risks that blood donors from a lower class were taking…

CATHY VO: …all of that prompted Tanmaya to re-think his independent life in America, to re-think Tanmaya 2.0.

MUSIC: Drum and bass join the dreamlike piano to create a lo-fi hip-hop beat

CATHY VO: Especially compared to his dad’s more interconnected life in India.

TS: My mother is a very spiritual person. She always says that,

TS: “Things happen to people because there are lessons that people need to learn.”

TS: And I think from my, from my own personal selfish perspective, like, this needed to happen so that I learned certain lessons.

TS: So that this thing that I was doing with like running away from my family, I stopped doing that.

Cathy: And I know that, you know, your family lived in the U.S. for a little while before moving back to India. Do you think you understand now a little bit more, why your dad chose to live in Dhanbad instead of staying in the U.S.?

TS: I think so.

TS: I think so.

TS: I - I - actually, that's one of the things I spoke to him a lot, because even in his time, a lot of like, you know, a lot of his close friends with other people from India, you know, in the university, in California, in Berkeley.

TS: And he said that so many of them talked about maybe moving back to India, but nobody did.

TS: All of his friends, except for him, they eventually settled in the U.S. and he was the only one in his friend group who came back.

TS: I feel like I'm in the same stage of life myself, you know, I've spent a few years in the U.S., I've been building a life in the U.S., so I feel like I'm in the same situation as in my father.

TS: He definitely took a harder decision in terms of like, you know, material comforts in terms of like, money and career, like, he could have gone much further…

TS: But he doesn't have any regrets, and I have a feeling that that's what I'm also headed.

CATHY VO: Today, Tanmaya is more in touch with his family than ever. And while he’s still pursuing his dream life as a filmmaker, he’s been spending a lot more time in India — and finding out what it’s like to make his family a bigger part of his life.

MUSIC: Drum and bass join the dreamlike piano to create a lo-fi hip-hop beat

MIDROLL: Promo for At the Moment

Janrey Serapio: Hey there! I’m Janrey Serapio.

Sylvia Peng: And I’m Sylvia Peng.

JS: We’re the hosts of At the Moment, an Asian American news podcast.

SP: Every other Tuesday, Janrey and I tackle the everyday politics that shape Asian American communities.

JS: At the Moment is produced by AZI Media, an independent news organization founded by Zillennial Asian American journalists and storytellers.

SP: You can find our podcast at www.azi.media.

JS: Or look up At the Moment: Asian American News on Spotify, iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you listen.

SP: Check us out, and see you on Tuesday!

Segment 2: Delma and Delvin

CATHY VO: This is Self Evident. I'm Cathy Erway.

MUSIC: A mellow R&B song begins

CATHY VO: We heard from Tanmaya about how his dad’s community — co-workers, family, friends, people he’d helped over decades — all came together to help Tanmaya get to India, and make sure his family could survive COVID.

CATHY VO: Seeing those relationships and taking care of his parents changed the dynamic between Tanmaya and his dad.

CATHY VO: Being a caregiver can change so much of a person’s life – but especially when your support network doesn’t have a lot of resources to offer.

CATHY VO: To hear how that can feel, I'm passing the mic to Angela Edward, a social worker from Michigan , who also hosts her own podcast – For Micronesians By Micronesians .

CATHY VO: Angela reached out to us to talk about her aunt Delma, and Delma’s son Delvin, who has cerebral palsy.

CATHY VO: The way Micronesians in the U.S. qualify — or don’t qualify — for health insurance can be really complicated. In 1996, the right to apply for programs like Medicaid and SNAP — which were available to a lot of Micronesians who had moved to the U.S. — was actually taken away by the federal government, as part of so-called “welfare reform” legislation.

CATHY VO: Then in 2020, part of a COVID relief package gave Medicaid back to these communities.

CATHY VO: But even though they’re technically now eligible, getting help isn’t easy.

CATHY VO: Here’s Angela.

MUSIC: R&B song breaks down and ends under Angela’s voice

ANGELA VO: In October 2021, I took a trip to a small-town in Southwest Missouri for my dad's 60th birthday.

ANGELA VO: There's a whole community of Micronesian folks who've settled in the four-state area , including a lot of my extended family. Having this chance to gather was a really big deal, because ever since the pandemic started, we've all been reeling from COVID .

ANGELA VO: That was one of the first things I talked about with my Aunt Delma, when we were catching up. How her friends and neighbors were coping. And who we've had to say goodbye to.

Angela Edward: Ethlene’s brother just passed away after the funeral...

Delma: That's five so far.

AE: Oh my God.

D: But there's, uh, more Pohnpeians that passed away with Covid, too.

ANGELA VO: Delma caught Covid during the summer of 2021.

ANGELA VO: She was in the hospital for two weeks. And when I saw her, she was still having trouble with her daily routine.

ANGELA VO: And that was a real problem, because for the past three decades, Delma's daily routine has been taking care of her son, Delvin.

ANGELA VO: Delvin has cerebral palsy. It's a neurological condition that impairs the body's ability to move .

ANGELA VO: Since he was born, Delvin's diagnosis has stopped him from doing things the rest of us take for granted. Like walking, talking, eating, and showering.

ANGELA VO: Thankfully, when Delma was hospitalized with Covid, her family stepped up to help out.

ANGELA VO: But she's taken a long time to recover from the infection, and now it’s much harder to take care of Delvin the way she used to.

D: I think the COVID affected a lot of people with they're, you know, like, energy and stuff.

D: It makes you weak.

ANGELA VO: The whole experience made her stop, and recognize that she can't keep going like this.

ANGELA VO: At the time that I'm sharing this s tory, Delma is 47 years old. And Delvin is 30.

D: He's an adult. You know...

D: I'm not that old. I don't think I am, but one of these days, you know... yeah. I'll, I'll get to where I cannot pick him up anymore, so... I'll need more help.

ANGELA VO: Every morning, Delma runs the faucet in the bathroom of their two-bedroom apartment.

ANGELA VO: One of the effects of Delvin's condition is that his teeth are really sensitive .

ANGELA VO: So she grabs a washcloth, squeezes a little toothpaste onto it, and starts rubbing it gently onto his teeth.

D: So I go, uh, rub it on his teeth, cause it bleeds every time…

ANGELA VO: The whole process takes about fifteen minutes.

ANGELA VO: It's not one of Delvin's favorite things.

D: …He don't like the toothpaste. Whenever he sits up and I brush him, he spit it out most of the time.

ANGELA VO: With a lot of these daily tasks Delma does for Delvin, there's always a little risk that something might go wrong, and end up hurting him.

ANGELA VO: Like here in the bathroom, she's making sure his teeth get cleaned, but also making sure he doesn't accidentally inhale the toothpaste foam, and choke.

D: Sometimes it's hard for him to spit it, so what he do is try to swallow it, so it's better with the wash cloth...

MUSIC: An intricate mix of string instruments and ambient electronic percussion begins

ANGELA VO: Delma moved to Missouri from her home island of Pohnpei, in Micronesia, when she was 24, specifically to mak e a better life for Delvin.

ANGELA VO: She came to be a nursing aide — thinking that she'd make more money, and learn how to better take care of Delvin in the future.

ANGELA VO: But her employer required her to live in a corporate apartment, sharing three bedrooms with five other workers. Then garnished all of their wages to pay for a monthly rent — that felt too high for their living situation.

ANGELA VO: So Delma quit. She started working in restaurants, then on the assembly line for furniture companies.

ANGELA VO: When she made the decision to move to the U.S., Delma says she was also was thinking about physical therapy, and different kinds of furniture and assistive living tools in the States.

ANGELA VO: She thought that relocating would help her get access to the kind of health care technology that wasn't available in Pohnpei .

MUSIC: Ambient music fades out under Delma’s voice

D: But that's not what happened.

D: Cause when I first brought him over, my insurance wasn't enough to cover for him to get a chair.

D: So I tried to get help and I thought I was going to get Medicaid to at least help get his chair, and that didn't work.

D: When I asked help for Delvin and they said, "No"...

D: They said "He's not eligible, ‘cause he's an Islander."

ANGELA VO: When Delma and Delvin moved to Missouri, they were ineligible for Medicaid, because Micronesian migrants were disqualified from that program in 1996 .

ANGELA VO: Delma's mom, who used to help watch Delvin at home, passed away in 2005. So Delma had to stop working full-time.

ANGELA VO: And over the past 23 years in America, Delma's gotten stuck in a catch-22 that a lot of Americans live with: She thought she could earn more money, get health insurance, and take better care of her family…

ANGELA VO: …but because she has to take care of her family, she can't hold a job to earn more money or pay for health insurance.

ANGELA VO: So Delma, her fiance Yos, and their Micronesian community are Delvin's health care system. And she is his full-time caregiver.

SOUND: The bath runs

ANGELA VO: Every day, she gives Delvin a bath. Using a washcloth to rub soapy water onto his body.

D: Whenever he takes a bath, he got so excited that he'll want to jump.

ANGELA VO: She puts on his diapers and changes them two to four times a day.

ANGELA VO: She cooks all his meals and feeds him by hand...

D: When it comes to Delvin, he loves eating.

D: He's not picky with anything.

MUSIC: A languid, mellow beat with melancholy guitar melody begins

ANGELA VO: Because they can't afford the right kind of wheelchairs or transfer chairs, Delvin spends most of his day inside. Usually lying on an island mat on the floor, watching TV.

ANGELA VO: And since he can't really move around, Delma checks in every day to see where he's sore, or cramped, and massages his muscles.

D: It's hard, but I ask him from his toe up to his head, to find out if there's something wrong with him.

D: If he said he has a headache, so I massage his temple, like, you know, his forehead and stuff.

D: Sometimes I'm giving massage on his feet, cause his leg is stiff.

ANGELA VO: Delvin's never been able to communicate with words, the way Delma and I can.

ANGELA VO: And he's not neurotypical, so he can’t problem-solve on his own.

ANGELA VO: He isn't able to maintain a daily schedule, pay for bills, or make life plans, without Delma.

ANGELA VO: Watching Delvin and Delma communicate is beautiful, though. She’s his mother.

ANGELA VO: Even if he can't say words… she can tell when he's hurting, happy, sad, excited, or bored.

ANGELA VO: She knows what his favorite TV shows are, who his favorite people are, and knows his sense of humor.

MUSIC: Languid, mellow beat ends

D: Delvin is, uh... sometimes you can say he's silly.

D: My dad, he's from a different island, you know, back home. And my mom is from a different island. So they have different language, like dialects.

D: He laughs when you speak my mom's language. He thinks it's funny.

D: And it makes me laugh a lot 'cause when he laughs, you'll have to laugh too.

ANGELA VO: Delma's entire life would change if she could get public health benefits.

ANGELA VO: But she's tried three times. And told us that every single time, she was rejected, because she's not a citizen.

ANGELA VO: When I asked her if she's tried to apply for citizenship, she turned around and asked me,

Delma: Can we? That’s the question. Can we Islanders become citizens?

ANGELA VO: Because of all the experiences she's had — being rejected by the health care system, watching family members threatened with deportation, and feeling confused by all the paperwork she gets asked for by government officials… Delma's question is pretty reasonable.

ANGELA VO: There is a process for Islanders like her to become naturalized, or get the same benefits as a U.S. citizen .

ANGELA VO: But I don't think she's ever seen it work in reality.

ANGELA VO: Delma moved her whole life here to make new opportunities. But she understands that Islanders in the States are at the mercy of the American government.

D: Without the care that, you know, they're rejecting for my son... you cannot do anything without that kind of help.

D: You know, we want to go somewhere. We want to go have fun, but we cannot. 'Cause we don't have the right chair to take him in, and...

D: I like Missouri. It's just that if you don't have money, then it's hard.

D: You know? like...

D: Sometimes, I ask this question: "Why do I come over?"

D: What I see in the future is... maybe we should go back home. Yeah. Just go back home.

ANGELA VO: But moving back home wouldn't necessarily make life easier.

ANGELA VO: Some living costs would be lower , and some ways of life would be more familiar, more comfortable.

ANGELA VO: But after Delma’s family moved to the States, their house fell apart — literally. So they'd have to buy a new house.

ANGELA VO: And taking care of Delvin without specialized equipment and facilities would be just as hard on the island.

ANGELA VO: So Delma's best bet is to keep pushing for benefits in the States. As a Micronesian American.

ANGELA VO: And right now she has the first chance she's ever had at getting public health care.

ANGELA VO: In December, 2020, the Federal government passed legislation that made Micronesians eligible for Medicaid .

ANGELA VO: Delma applied. But she missed the phone calls and mail notices from the caseworker who was reviewing her application. So she still doesn’t have health insurance.

ANGELA VO: She's still really wary of the process, and every time Delma’s rejected, she feels more defeated.

D: When people want, uh, needs help, they should ask for it...

D: But asking for help... it hurts your pride.

D: It's hard to do.

D: I think it's the way I'm raised.

D: And sometimes, you know, when I ask for help it's...

D: It's kinda embarrassing, you know, if you ask?

MUSIC: A bluesy, key-board driven beat begins

D: Rejection is not a good thing.

ANGELA VO: But a bigger reason Delma doesn't ask for help is that she's always afraid of what would happen if she got the government involved.

ANGELA VO: She started feeling this way in 2007, when two of her younger relatives were separated from their parents.

ANGELA VO: What happened was that one of those kids got into some trouble at school. That led to the school calling Child Protective Services , who interviewed the parents and removed the kids from their home.

ANGELA VO: Delma ended up working with the case manager while the kids were in foster care. But she never got them out of the system.

ANGELA VO: And this experience still comes up when Delma thinks about accepting help from a government program.

D: They stay in the foster care.

D: That time it was, it was hard, for me.

D: Every time I think about em, I cry.

D: I asked the quote, "case worker"...

D: I asked her, I was like, "Why is it that when we ask for help from you guys, and then you guys rejected us, but then you guys have the right to take away our kids?"

D: You know? I just don't understand that.

ANGELA VO: Being from this family, I know what it’s like to be Micronesian. And being a social worker, I understand what's supposed to be ethically appropriate for my job.

ANGELA VO: But social work ethics aren’t always looked at through the right cultural lens. The work to understand where your clients are coming from isn't always there. And it's so easy for Micronesian people to fall through the gaps.

MUSIC: Bluesy, key-board driven beat ends

D: It's kinda like a nightmare to me, sometimes I want to try a lot, way, way, way more than like what I'm doing.

D: But then it scares me.

D: Cause with Delvin,

D: When people come visit and they leave, he wants to go with them, and then he's, he sometimes bit himself like he just... there's like scars here on his arm where he, he, he got mad, and then he bit.

D: And then he's... he's getting where —

AE: (Sniffs because she's tearing up)

AE: Wiping my tears…

AE: …You made me sad.

D: I'm sorry.

AE: It's okay.

D: Should we rest for a little bit?

AE: Yeah, we can take a second. It's okay.

AE: That whole situation makes me sad. (laughs with exasperation)

D: (Speaks in Pohnpeian)

D: I'm trying to be strong too, because every time I think about this and I talk about it, I cry, but I am trying to be strong today. (laughs)

MUSIC: A wistful, low-fi hip-hop beat begins

ANGELA VO: Some people look at this situation and ask, why can't my aunt become a citizen? Why hasn't she already registered for the benefits she's entitled to?

ANGELA VO: But my question is... How can we invite someone to our country to work in the health care system but not give them any health insufgarnishrance?

ANGELA VO: How can we look at a parent who’s trying to take care of someone with a chronic disability, and refuse to help them at all, because they were born in the wrong place?

ANGELA VO: We're just starting to change that now by giving Medicaid back to Micronesians . But we can do a lot more for people like Delma, to help them take care of their families.

AE: Is there even a word that translates for "caregiver"? In Micronesia, if caregiving is a word?

D: I don't think there's a word for "caregiver" back home because we take care of our elderlies until they passed .

D: But nowadays that most of the Islanders are here, I can see that some of them are doing the caregiver thing.

ANGELA VO: Giving care is everything in this family. The times that Delma and Delvin enjoy most are just… everyday moments.

ANGELA VO: OK, maybe not the tooth brushing.

ANGELA VO: But you know, watching movies, listening to music... the simple things they share with each other make them happy.

SOUND: Video chat ringtone

Angela VO: Halfway through the afternoon Delma gets on a video call with her sister-in-law Connie.

MUSIC: Wistful hip-hop beat ends

(Delvin croons with excitement)

AE: You're excited already?!

D: Even saying Connie's name.

Connie: Deleveeeeeeen!

D: Look who is that

D: Hahaha

D: Look, he's excited but has a serious facial look that says, "Don't lie to me!"

(Delvin grunts and Delma laughs)

ANGELA VO: I love my Aunt Delma and my cousin Delvin. They're special to me, but what they go through — living a life that's closed off from the system they live in — feels like the reality for a lot of Micronesian Americans.

ANGELA VO: With a little help from me, Delma's going to get her newest Medicaid application done and hopefully, finally, get some of the help that she was hoping to find 23 years ago.

ANGELA VO: Before I leave Delma's apartment, I ask her what she thinks is her favorite part of being a mom.

D: Best part of it is...

D: ...that God bless you with your kids.

D: You know, I was just in high school when I had Delvin, so it was hard. But I never regret having him.

D: It's a blessing to me...

D: Yeah. That's our moms’ thing, you know.

D: Sometimes we get tired, but…

MUSIC: A slightly dreamy hip-hop beat begins

D: We're happy every time we do stuff for our kids to make them happy and, and healthy. We – being there for them all the time.

Credits

CATHY VO: Thanks so much to Delma, Delvin, and Tanmaya for sharing their stories with us.

CATHY VO: If you liked today’s episode, please share it with a friend, and write us a 5-star review for Self Evident on Apple Podcasts! It really helps people find the show.

CATHY VO: This episode was produced by James Boo, Emily Wu Pearson, and Angela Edward.

CATHY VO: We were edited by Julia Shu.

CATHY VO: And we were fact checked by Tiffany Bui and Harsha Nahata.

CATHY VO: Angela’s podcast, For Micronesians by Micronesians, covers more topics affecting Micronesians and other Pacific Islanders — including adoption, fat-phobia, and mental health. We’re leaving a link in our podcast, so you can check it out.

CATHY VO: Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda.

CATHY VO: This episode was made with support from PRX and the Google Podcast Creator Program — and, of course, our listener community.

CATHY VO: I'm Cathy Erway. I hope you’ll keep in touch.

CATHY VO: Remember to take care of yourself, and take care of each other.

MUSIC: Hip-hop beat ends