Bonus: Diaspora DJ Roundtable 2021 Feat. Les Talusan, Arshia Fatima Haq, and Roger Bong

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

Community Producer Rochelle Kwan (a.k.a. YiuYiu in her DJ life) gathers the DJs who joined her in curating our first annual mixtape — to chat about how we can use music to reconnect our diaspora communities, across generations and borders.

If you haven’t heard the mixtape — which features musical selections by Les Talusan (a.k.a. Les The DJ of OPM Sundays), Arshia Fatima Haq (of Discostan), Roger Bong (of Aloha Got Soul), and YiuYiu (of Manhattan Chinatown) — then you can hear it here, or wherever you get podcasts.

Need more music? Did we miss a favorite track of yours that the world absolutely needs to hear? Then check out our public Spotify playlist (a totally separate, community-sourced playlist that we’re pairing with this mixtape) to hear a bigger range of tunes from Asian and Pacific diaspora cultures — and add your own favorites!

Credits:

Produced by Rochelle Kwan and Julia Shu

Music curated by Les The DJ (a.k.a. Les Talusan), Arshia Fatima Haq, Roger Bong, and YiuYiu (a.k.a. Rochelle Kwan)

Edited by James Boo, with help from Sheena Tan

Sound mix by Timothy Lou Ly

Self Evident theme music by Dorian Love

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

Self Evident is a Studio To Be production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts creator program — and our listener community.

About the DJs:

Les Talusan a.k.a. Les The DJ

Les The DJ aka Les Talusan is a DJ, photographer, curator, teaching artist and organizer whose practice immerses people in the joy of discovery, empowerment, and community. This approach is informed by Les’ own story of resilience, liberation and courage as an immigrant, mother and v/s.

Born and raised in Manila, Philippines, Les fell in love with music at a young age, DJing at local clubs and playing in bands. Les has lived in Washington, DC for over 20 years and continues to expand their talents, performing behind the decks in the U.S. and abroad.

Arshia Fatima Haq - @discostan | @arshiaxfatima

Arshia Fatima Haq (born in Hyderabad, India) works through film, visual art, performance, and sound, in feminist modes outside of the Western model. She is interested in counterachives and speculative narratives, and is currently exploring themes of embodiment, mysticism, indigenous and localized knowledge within the context of Sufism.

She is the founder of Discostan, a collaborative decolonial project and record label working with cultural production from South and West Asia and North Africa. She hosts and produces radio shows on Dublab and NTS, and has produced episodes for KCRW's acclaimed "Lost Notes" podcast series. Her work has been presented nationally and internationally at museums, galleries, nightclubs, and in the streets.

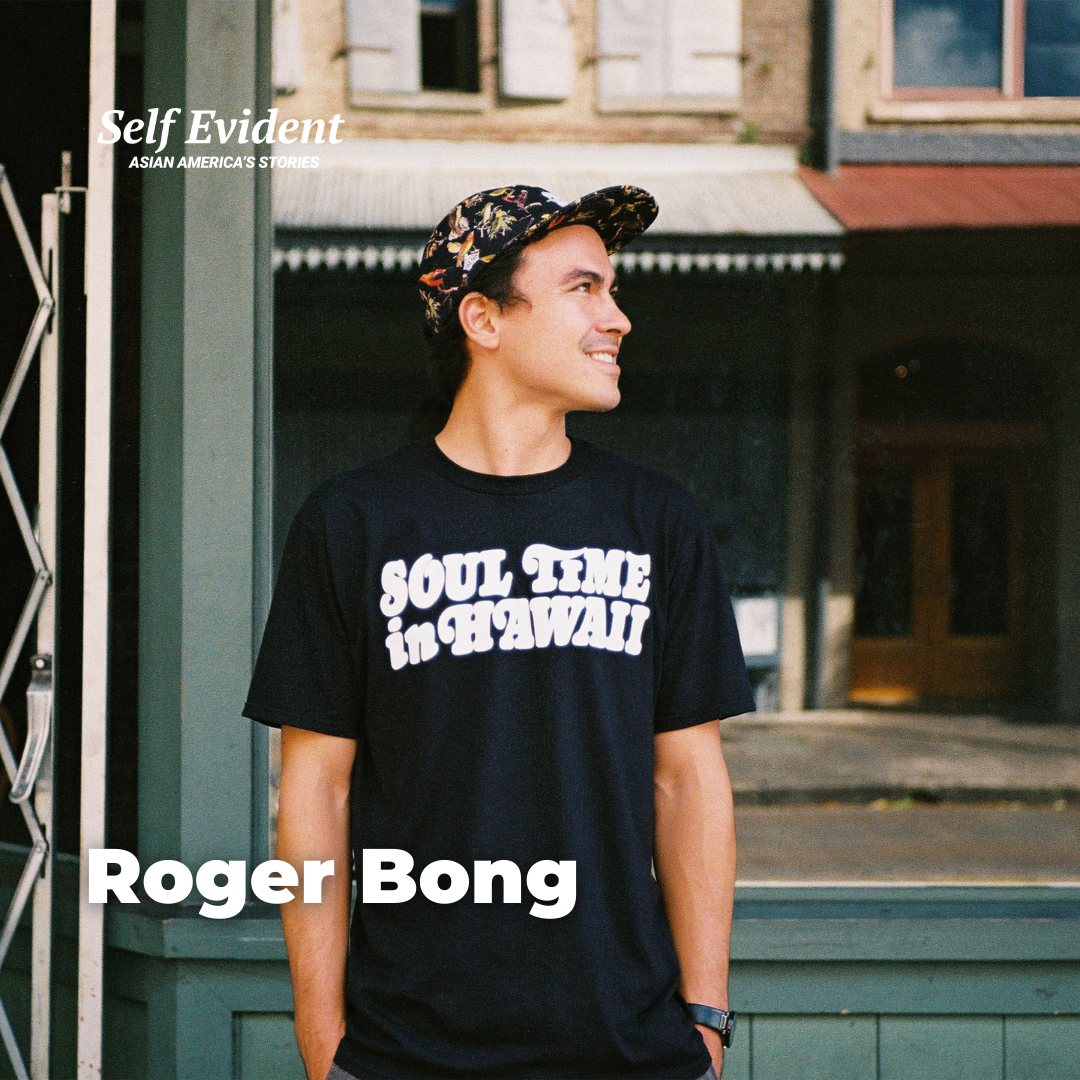

Roger Bong - @alohagotsoul | @rogerbong

Roger Bong launched Aloha Got Soul as a blog in 2010 after graduating college with a journalism degree and — more importantly — after hearing DJ Muro's Hawaiian Breaks mix. Roger's love for story, sound and design has turned the blog into an independent record label that champions all genres and generations of music from Hawai‘i. He and his wife run the label from Honolulu.

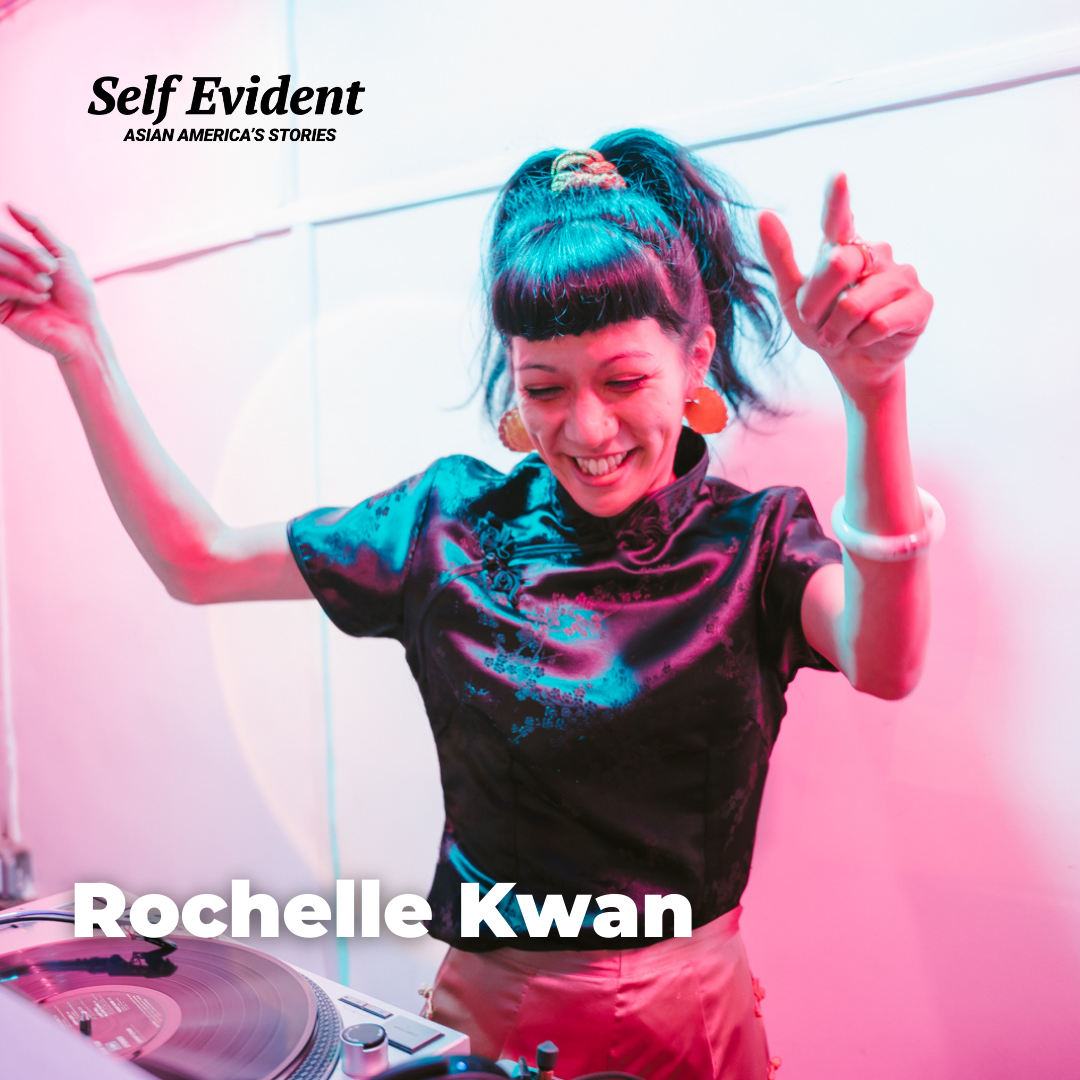

Rochelle Kwan a.k.a. YiuYiu - @rochellehkwan

Rochelle Kwan, also known as YiuYiu, is a cultural organizer, oral history educator, and DJ based on Lenape land in NYC’s Manhattan Chinatown. Bringing together her backgrounds in organizing, history, and music, she trains everyday people to build multigenerational oral history projects and engage with their communities as classrooms. As a cultural archivist, DJ, and dancer, she works to amplify arts and culture as essential to community resilience and foster intergenerational relationships and dance floors.

Rochelle’s also the Community Producer at Self Evident, where she leads our budding oral history program and helps to grow our listening party program through partnership and collaboration.

Transcript

ROCHELLE VO: Hello, Hello! This is a brand new voice here on Self Evident. I am Rochelle and I am our community producer here.

ROCHELLE VO: I am also a very new DJ! And so as a still-learning DJ, I brought some of my friends and DJs that I look up to in conversation to learn from each other… not just about music, but also about the relationships and stories behind their work and the music that they play.

ROCHELLE VO: So we have our Arshia Fatima Haq from Discostan. We have Les Talusan AKA Les the DJ from OPM Sundays, and we have Roger Bong from Aloha Got Soul.

ROCHELLE VO: You can learn more about our DJs and their work on our show page at selfevidentshow.com.

ROCHELLE VO: And to hear our first annual diaspora dance mix tape from Arshia, Les, Roger and me, tune in to our latest episode by subscribing to Self Evident wherever you get your podcasts.

ROCHELLE VO: Enjoy!

Rochelle Kwan: So the folks at Self Evident had started hearing about the music stuff that I've been doing here in Chinatown and asked me if I wanted to help produce a mixtape and a conversation with a few DJs. And y'all were the first people that I thought of because as I'm kind of making my way through the music and DJ world beyond just being a dancer, I have learned a lot from you all in how to bring community and history into music and deejaying. So why don't we start by introducing yourself by telling me your name, your pronouns, and what you're working on.

Les Talusan: Well, hello, there I am Les Talusan and AKA Les the DJ here in Piscataway land, Washington, DC.

My pronouns are she/they/them…what am I working on? What am I not working on right now? They usual. OPM Sunday's original Filipino music. I do that. And I'm also on Thursdays.

Rochelle Kwan: Now we're going to do like classroom style and you're going to popcorn to someone.

Les Talusan: Oh, I didn't go to a school in America, so I don't know what that means, but I'm going to pick Roger.

Roger Bong: Thank you. So exciting to be here. My name is Roger Bong. I run a record label called Aloha Got Soul here in Honolulu. And our focus is on music from the islands of all styles, all generations, everything from, you know, rock and roll made in the sixties all the way up through new age electronic stuff made in the nineties to music that's being created today.

Rochelle Kwan: Did you go to school in the U.S.? Do you know what popcorn is?

Roger Bong: Yeah, I did go. I went to school in Mililani — Mililani High School. For all those people listening. Good to meet everybody here. And Arshia, would love to hear your story.

Arshia Haq: Hi everyone Arshia here, and I do a lot of different things, but the music side of my work is called Discostan, which is now in its 10th year. It started as a radio show and turned into a nightclub event, kind of in collective and also a record label focusing mostly on music from the SWANA region — Southwest Asia and North Africa — both old and new. And currently working on first actual night events since the pandemic started, which will be a fundraiser for what's going on in Afghanistan.

Rochelle Kwan: Amazing. So I guess just to get us warmed up, I'm going to actually have us jump all the way back to our first memories of music and how we really got into music in general. The first question that I'd love to hear from you all is could you tell me about where your love for music first started? Arshia, can we start with you?

Arshia Haq: Sure. So it's a story that I love telling, but I got my first cassette when I was in India, which is where I was born. I was around age four. My dad was a big music collector. He took me, when I was four, to a cassette shop that was on our street and let me pick out something of my own. And I picked out this cassette by a woman named Runa Laila, but it was this super disco meets South Asian disco, Bollywood cosmic extravaganza. And at that time I didn't really know what it was, but it was a very formative sound for me. Not long after that we migrated and there was still a lot of back and forth, so music was kind of the bridge or how I navigated moving between two worlds from a very early age.

Rochelle Kwan: I know that you said that that happened when you were four, but do you happen to remember from when you were four, why you chose that one cassette?

Arshia Haq: The cover is basically a woman that looked like someone that would be from my family, but in this amazing futuristic gold outfit with a microphone in her hands and kind of looking at the camera very directly . And it was just this very powerful and strong and also was something I could project myself on to because it looked like someone, you know, that I would see in my neighborhood.

Roger Bong: I think my earliest memories are at my grandmother's apartment. She had this one of those old, like big consoles or cabinets with the built-in speakers. And you put like the records in, and then after it's done playing one record, it kicks the next record in and drops it down. My brother and I would go through her collection and listen to her records. That was like my earliest memories of actually intentionally enjoying music that we would dance around in her living room and whatnot. It really goes back to those early years of just spending time with grandma.

Les Talusan: Growing up in the Philippines, music is just everywhere. One of my earliest memories that's like embedded in my brain is a neighbor's clapping to the sound of a Cure song to call to each other. “Close to Me” by the Cure. But also my parents are big music fans to put us to nap. My mom would put on mellow touch radio, which is the adult contemporary radio. And also my grandparents would always have the TV on and, um, you know, noontime shows in the Philippines, it's all singing and dancing. That's my early music memories, like having a tape tape in Minus One.

Les Talusan: I don't know if y'all are familiar with minus one, but before it was called karaoke here, like it's a Minus One , the voice. So I had a bunch of Minus One tapes, I would sing to Lea Salonga , I guess folks are familiar with her work on Broadway and, you know…

Rochelle Kwan: Aladdin.

Les Talusan: Aladdin. Exactly. But like, I know her as a child singer.

Rochelle Kwan: A lot of my early music memories came from when it became karaoke. So next step after Minus One, my parents would host these big karaoke parties at our house and singing in Cantonese, singing all the songs that we would listen to in the car. Even though I grew up speaking Cantonese, a lot of the Cantopop songs are very romantic songs.

Rochelle Kwan: And so that was not part of my everyday Cantonese vocabulary at home. So I didn't understand anything that they were saying, but I knew that it was Cantonese. And like sometimes today when I hear songs that I heard in my parents or my aunt's car, I will immediately flash back to that and feel like I'm a kid again.

Rochelle Kwan: So I think that's where I first got into music is just from growing up with it as well. Just kind of like everyone, it sounds like our families and our homes were really the place where music came alive for us. Do you remember your first musical purchase or gift and when and what was it?

Les Talusan: I think it's Head on the Door by The Cure. That's what I remember.

Roger Bong: The first CD I ever bought, which is the first piece of music I ever bought was Operation Ivy. You know, my brother was listening to a lot of punk and that kind of music. And I was like, yeah, I want to get into this too. So he drove to Tower Records and, um, Pearl City.

Roger Bong: And that was the first city I ever bought. And it's funny cause I remember my brother on the way home. He's like, “Oh, maybe we shouldn't play this in the car. Just wait till you get home, Roger. Dad’s probably not gonna want to hear this.”

Arshia Haq: I can share what my next purchase that I remember was which was when I was in suburban America, I wasn't allowed to listen to American music, but I got to go to the mall and I had some saved up some money.

Arshia Haq: So I like promptly went to the store and bought Madonna's Like a Prayer also in cassette. And then I went to the video game arcade in the mall and then promptly lost the cassette. It was a very tragic story.

Les Talusan: So weird before you said Madonna, I was like, I wonder if she got Madonna.

Rochelle Kwan: Not allowed to listen to American music and then jumps straight into Madonna.

Rochelle Kwan: I don't remember my first solo music purchase, but I remember my parents... I think it was specifically, my dad convinced me to buy the ABBA Golden Hits album with him. And he was like, “Yeah, this is a really, really good CD. You should buy it with the money that you….” I can't even remember. It must have been allowance from him.

Rochelle Kwan: And he was like, “Yeah, you should buy the CD.” And then the moment that I arrived home, the city disappeared, and I'm pretty sure he had it, but that was my first musical purchase that I also lost. But I think it's somewhere in my home.

Roger Bong: My brother used to try and do that to me when we would go to like Tower.

Roger Bong: “Yeah, you should buy this.” I think I was a little too clever to be like, “No, I'm going to keep looking around.”

Rochelle Kwan: Well, I'm glad one of us made it out of there. Do you all remember a time when you became totally obsessed with a song or an artist that you'd never heard before?

Les Talusan: Like all the time.

Rochelle Kwan: Describe one of them or describe the feeling, tell us from honeymoon phase through finding your next bae.

Arshia Haq: I remember when I heard Smells like Teen Spirit for the first time on the radio. And it was kind of crazy because I'd never heard anything that sounded like that before and was really moved by it. And in retrospect, I think what I really liked about it is that there's something very similar in the instrumentation or notation of Indian classical music.

Arshia Haq: You can actually hear it in a lot of Kurt Cobain's early work. So that was kind of the first time I remember hearing something and being very shocked and also just drawn to it immediately in terms of something that was from my immediate environment. But beyond that, I think it was when I started working at a record store and found Turkish music, Turkish psychedelic music for the first time.

Arshia Haq: And this is kind of like maybe early two thousands when reissuing international music was just starting to become a thing. Because before that, no one cared about music from our regions, so hearing that music and hearing kind of the similarities between some of the stuff I'd heard growing up, and also hearing words that I could make out.

Roger Bong: So right before I graduated high school, I actually borrowed some records from a friend's dad who was really into local music from the seventies, which is this breezy, super positive sound that kind of blends jazz and soul and AOR and rock. One record by Mackey Feary Band . I was just like, “Wow, this is such a great record.”

Roger Bong: And then I graduated, moved to Oregon to go to school . Finished school, lived in Portland for a year. And while I was living in Portland, I heard this mix called Hawaiian Breaks that this DJ from Tokyo put out — DJ Muro. And I was like, well, how cool is this? This digger from Tokyo is like putting all these like local records, which I had no idea existed.

Roger Bong: 2010, living in Oregon, heard this Japanese DJ make this mix tape about like soul and funk and jazz from Hawaii and right smack dab in the middle of that mixed tape was a song by Mackey Feary band. And the song was called A Million Stars. And like right in that moment, all these memories of just listening to this record over and over and over again in high school just came right back. I was really homesick at that time, I'd been away from Hawaii. I was like, okay, this guy is doing something really interesting by excavating all these groovy sounds from the islands that I call home. Almost none of this music I'm even aware of because my family didn't really have any roots here before we moved here.

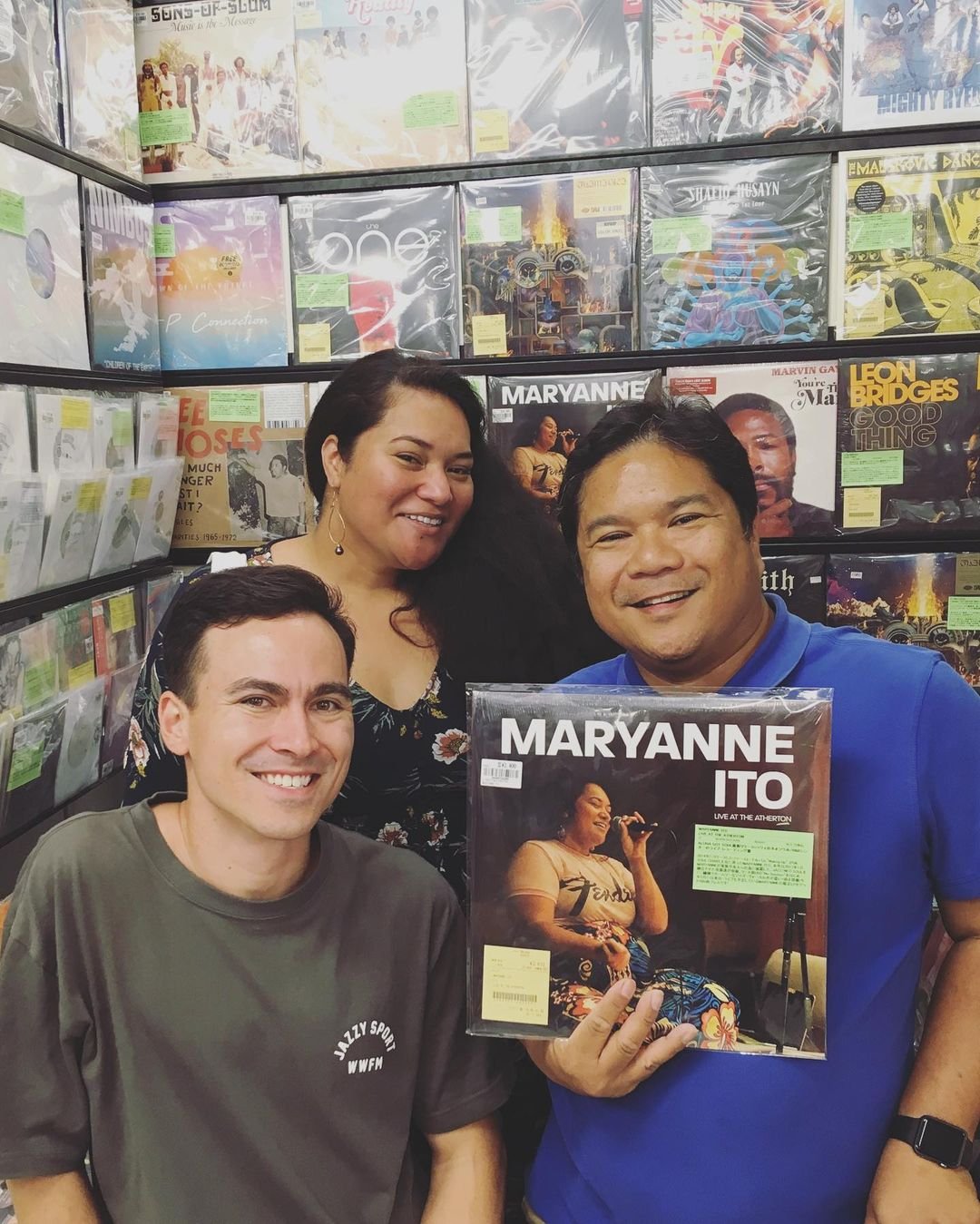

Roger Bong: And I looked online and there was nothing, pretty much nothing about any of these artists. There wasn't even a track list. DJ Muro didn't even put out… in true like digger fashion. Right. He didn't put a checklist out. He did all the work and wanted people to do the work if they wanted to know. So yeah, that's pretty much the reason why I started Aloha Got Soul 11 years ago now is because I knew that there was a need to identify all these songs that were in his mix and share these songs, like “A Million Stars'' with people. And so, like I said, I'm, I'm like still going off of this. We just re-issued Mackey Feary band's record in July of 2021. So it's come full circle and we're still going.

Rochelle Kwan: So you could listen to it over and over and over again from now on. I just real quickly,

Les Talusan: I just wanted to say. I love Mackey Feary as well. And Rog, you saw, I ordered a couple of copies and they have the original pressing, the Japanese pressing, and now the Aloha Got Soul . I'm so annoying… anyways. Yeah. And that's how I found Roger online, you know, just like Googling things, you know? I think my first order was an hour record.

Roger Bong: Yeah, I think so. And then you showed up in Hawaii and we were doing a record fair. And you bought the Aiko seven inch, I think you're, I think Oscar, Oscar, Oscar, who's like super into city pop in Japanese music and he's like, “Aiko, what? Oh my gosh.”

Les Talusan: Yeah, we met at a record fair. But my song, nothing deep, nothing connected to the Filipino stuff that I play. But, uh, My Bloody Valentine's “Loveless” the whole album and not even a song, the whole album. When I first heard it, I was a teenager and was really, really obsessed with that sound. You know, when you play a CD so much that they become a little… like the silver stuff, the print like goes away. That's what happened to that CD. I was so obsessed with that sound that I eventually had a shoegaze band because I'm obsessed with shoegaze.

Arshia Haq: Les, that was actually the album that crossed my mind first. I listened to it, I think almost every day for a few years in my early twenties, I knew every sound. I figured out some of the words, you know, there's so much in it. You can just keep discovering.

Les Talusan: Until now, until now. When I listen to that album, cause sometimes I would DJ on Twitch, and I would do an all shoegaze set and the honeymoon phase is still there. Still obsessed.

Rochelle Kwan: Oh, I love that there are so many memories that just kind of popped up from all of the things that you said. Like, especially Les when you're talking about the CDs wearing out. My dad also, he has a big record collection, which I have been inheriting from him. He used to be so particular about his records, that he would pick out his favorite songs and then record them on a cassette tape. So he could play just his favorite songs and make a mixtape for the car, so he wouldn't have to keep playing his records and scratch the records. So what role do you all see music playing in communities, especially for folks in the diaspora?

Roger Bong: Hawaii is a pretty small place. Everybody knows everybody. And aside from music, one of the connecting factors, if you grew up here is what high school did you go to?

Roger Bong: You know, you went there so you might know this person. What year did you graduate? So that being said, where you're from in terms of what high school you went to, but also the music from here just instantly connects at least Hawaii’s diaspora. I've heard stories of people going to college on the West Coast or the East Coast and hanging out at a party.

Roger Bong: And they'll just throw on a song by, let's say, Kalapana, which is from the seventies, it was Mackey Fury's first group. And like somebody across the room will just be like, “Hold up, you know, Kalapana? You gotta be from Hawaii.” And so that will instantly connect those two people. If I'm going to connect it to what I've been doing, the record carries so much with it over the years.

Roger Bong: I mean, Rochelle, you know, you're inheriting all these family collections, right? And embedded into this vinyl are all these stories, not only from the musicians, but the people who own them. So there's so many ways, big and small, that connect people.

Rochelle Kwan: Would people know from the music they hear other people playing what high school they went to? Was it that specific?

Roger Bong: That’s a great question. I don't think it's that specific. It's more like, oh, who's your cousin kind of thing. But, but definitely like just the music in general — Three Plus, Kalapana, Ten Feet. All these kinds of island bands, like someone like Les, right? She discovered all this music from Hawaii just by digging.

Roger Bong: And it allows someone like Les who might not have any connection here previously to, to feel like she can be a part of it. And that door is wide open for anybody who is curious enough to walk through it.

Les Talusan: It's funny you gave Kalapana as the example, because anyone who I hear play Kalapana is either from Hawaii or from the Philippines, because they were really, really big back home as well . The Hurt became such a dance floor jam, and there's even like a Filipino remix of The Hurt .

Roger Bong: Do you have that? That is a rare record.

Les Talusan: Do you want me to send you to digital? No, I don't have the, I don't have the 12 inch. Someone's selling it for like $400.

Roger Bong: It’s at $1,000 right now .

Les Talusan: Oh, my God, I should've gotten the, no, I shouldn't have gotten that 400.

Les Talusan: So I moved here in 99 and I guess I started deejaying shortly after then here as well. Cause I've been deejaying in the Philippines, but I sneak in Filipino music to my gigs before just, you know, here in DC, there's not a lot of Filipinos . Compared to let's say Hawaii, New York or California, you know, someone was joking to me recently, like, “Oh, so are there a lot of Filipino DJs there?”

Les Talusan: I was like, not really. And they were joking how in San Francisco it's like every sneeze, there's a Filipino DJ. So I think, when I used to DJ at a store in the mall, and I would hear Filipinos in the crowd, I would start playing some Filipino music. And this is like records. I would bring records and CDs at this thing.

Les Talusan: And just to, just to connect with them. Right. But since the pandemic started, I've been deejaying online, doing all OPM sets. OPM is Original Filipino Music , but really it's OPM plus. Plus is roots, pop and covers from the Philippines and the diaspora. But what does it do to community? It's just… Filipinos, we’re underdogs.

Les Talusan: And I hate it. I want people to know that we make good music that we're everywhere, but we're nowhere. I just want to share our music. Every Sunday, Twitch is a gathering place. That's what it does is just, you know, together and hang out.

Rochelle Kwan: When you snuck in those Filipino songs, when you heard other folks in the crowd, what were those reactions like?

Les Talusan: Actually, I was hired by Smithsonian APA center to DJ an event with Filipino Americans from California . And the only thing that they said was like, play whatever you want, but then I was like, “Oh my God, I'm going to play all Filipino and Filipino American music.” And I started my set with Stockton, California’s own The Third Wave . They're a group of Filipinos sisters . And, you know, the reactions I got was someone came up to me and was like, I didn't know, our people made this kind of music. Because they were Filipino Americans and all they've heard are the foci. And then the more dramatic, like kundiman, which is a romantic love song, Filipino style, I was like, okay, I'm gonna, I'm gonna keep doing this.

Les Talusan: I mean, no one could stop me. I'm gonna do it anyways, even if they didn't like it, you know, I'm just very stubborn.

Arshia Haq: I think it's interesting that for all of us, it seems that the love came from family members. There is definitely, I think something about migration and the tie to music. And I think, you know, for the communities that I'm working with, especially because so many of our homelands are in conflict, there's a really important piece of that, which relates to embodiment and joy being part of how we resist. So even with doing this Afghan music fundraiser, you know, I really tried to find people that were in the diaspora from that community.

Arshia Haq: People would reach out to me and ask me to do radio shows or do this or that. And I was really kind of feeling like I can do that, but there's people from that community who should be making those playlists. Not me. I mean, I'm from the region, but there's a lot of silencing and de-centering that happens. And so we start in the club and bring these different diasporas together that have had pre-colonial and post-colonial shared traumas, especially post 9/11 and how that kind of changed a lot of things for anyone that looked Muslim in this country.

Arshia Haq: Also, there is this thing about, there are a lot of contentious lines and in our regions and songs can often be something that is a way to soothe the bruises and really bring some sort of kinship together, even in places where you might not find it. So, yeah, it's a way to embody all of the aspects. You know, it's also a place where you can all mourn together. When there's a conflict happening in your part of the world or some kind of issue, and no one else seems to care about it, it's one thing to be in a space with people who are oblivious to what's going on, and it's another thing to be on a dance floor with people who understand that history and that pain. And also to be able to come together is the form of, I don't know, resilience or celebration.

Rochelle Kwan: I love it, and I know that I've read something that you've written before about describing the origins of Discostan as a place. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Arshia Haq: Yeah. Yeah. So, I mean, obviously -stan is a suffix that means “land” . So that's why you have Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan or, you know, any of the -stans.

Arshia Haq: So being from two different places or multiple places and not being from anywhere at once, it was kind of this desire to create a fictional Republic that wasn't really about your national belonging and kind of was also a little bit humorous about how tied people become to their national idea. And also to really think about transnational connections again.

Rochelle Kwan: Yeah. That's something that I think a lot about with the records that I've been inheriting from folks, because like I was saying earlier is all of the records that I play are inherited from either my own family or from my neighbors here in Chinatown. And so often from when I inherit them from my neighbors, they tell me that the records just have all been sitting in their apartment for the past few decades.

Rochelle Kwan: And there have been multiple occasions where either their mom or their dad told them to throw it out and throw the whole collections out. And when I hear that my heart drops to think of not only the records themselves, but the fact that these are artifacts. From listening to them, it really feels like they were kind of a bridge for a lot of immigrants here in Chinatown, back to Hong Kong or China or Taiwan.

Rochelle Kwan: And like one of the biggest examples of that is that almost every single one of these records comes with a little booklet inside and it's a music booklet. It has chords. It has all of the lyrics. And as I was digging more into it and talking with my neighbors about it, they were saying that these booklets were meant for people in the Chinese diaspora to learn the songs across all dialects, because even if the song is sung in Mandarin, someone who speaks Cantonese could sing it. Someone who speaks another dialect can sing it. Every time I play the songs, so many of my neighbors know every single word. And so I wonder sometimes if they even ever looked at the booklet or if it was just because they heard these songs over and over and over again.

Rochelle Kwan: And so many people, even folks I'm not inheriting records from have memories of these songs. And so. It really feels like these records are not just me putting out a mysterious, mixtape that people will have to dig up the songs themselves. And that's something that I was really connecting with what you said, Roger, of like all of these different kinds of shows shouldn't be about us collecting music and hiding it away from people as the rarest ones that only we know about. Every time I put out a show, I put out a track list of every single song and artists that's on there so that people can start to dig for this music. Because if people don't know how to write or read Chinese characters, then it's hard for people to get started.

Rochelle Kwan: But once you trigger that YouTube algorithm, then you'll find so many just from one song. The work that I do with music is so much tied to these stories and tied to the people behind the music. So I would love to hear from you all, how, what is your process of learning about the people behind the stories and how do you incorporate that into your deejaying, into the labels, into all kinds of your work.

Les Talusan: I'm going to start because I don't have a record label. Okay fine Roger go ahead.

Roger Bong: No, I wanted to say something that before we move on, all three of you said something that resonated. So I'm going to try to connect the dots here. My family didn't have any ties to Hawaii when we first moved here. And in fact, my dad was born on the East Coast, but his parents moved to America from the Netherlands of all places.

Roger Bong: And not only that, they're originally from Indonesia, but they're Chinese. And so my heritage in terms of Chinese and who knows maybe even some Indonesian in me, I don't know, has essentially been severed because of these complicated Asian American ties or identities. And so, you know, one of the things that I struggle with is who am I?

Roger Bong: I was raised in Hawaii, but I wasn't born here. I love this music and I, I really try to do my best to champion it, but it's not like I have any native, Hawaiian blood in me. A lot of the times I asked myself this question, like not only who am I, but what is my purpose and why do I continue to do this thing that I do?

Roger Bong: And I think the answer ends up being like somebody has to do it. And if it's going to be me, I would like to do it in the most righteous way possible. And here in Hawaii, the word for that is “pono” — to be righteous to do something properly or with honor. So even though I don't have any roots in Hawaii prior to just growing up here, I still feel like a responsibility or a duty to bring this kind of music to the world.

Roger Bong: And Rochelle, I mean, you too with inheriting these collections. I'm sure there's a huge sense of duty on your part to not only share the music, but also the personal stories that came with them. Our identities are all over the map and music really grounds us.

Les Talusan: Uh, I am horrible and have forgotten your question. I am so sorry.

Rochelle Kwan: Well, the question is, how do you learn about and incorporate the stories and people behind the music into your work.

Les Talusan: By asking them directly. The artists that are still alive. Being partners with Joel Quizon for OPM Sundays, we decided a few months ago to do Usapang OPM. It means like OPM talk or OPM chat.

And we were able to talk to the people who actually made up the term OPM, which was amazing. We're trying to talk to more of the artists that we do play.

Rochelle Kwan: Why should people care about that?

Les Talusan: Know your roots. Right? I don't know. They don't have to care about it, but I care. I care that people know how things were started because this all spawned in the middle of the frickin, um, martial law, when the Marcos's were in power.

Les Talusan: But when you think about it, it makes me mad because it's like, uh, the Manila sound and the resurgence of OPM at that time was partially funded by, um, or maybe mostly funded by Imelda Marcos . She's horrible.

Rochelle Kwan: That reminds me too of, um, I've been digging a lot into the history of Cantopop, mostly from Hong Kong. And before the seventies, most of the Chinese music that was coming out was in Mandarin because there's a larger Mandarin speaking population. And so you'll sell more. But in the seventies and eighties, as Hong Kong was rapidly approaching the time when Hong Kong would be returned from the UK back to China, people in Hong Kong started realizing that they needed a Cantonese identity as Hong Kongers.

Rochelle Kwan: And so that's actually how Cantopop came about. People started singing in Cantonese because they wanted to create this identity and these artifacts of their language and of their culture. And when I first learned about that, I realized that I didn't know that it was part of the work that I was trying to do, but it makes sense to me now, because as I'm trying to also sort through all of the different identities that I hold, um, like you said, Roger, it feels like there's just so many moving pieces. And for me, this music and learning that there is history that has grounded this music gives me a little bit of stability, knowing that one, this music kind of arose in protest.

Rochelle Kwan: And two, to know that this music, it reminded my parents of home. For me that’s why it's important to know these stories behind the records, because I'm not just trying to pump out content. This music work that I'm doing is a way for me to connect to my identities and also trying to keep from feeling too lost in it.

Les Talusan: It's been simmering in my head, but I want to be the one to be able to share this music before white people figure it all out. You know, like I want people who look like me to be able to share our people's music. As I was discussing with Rochelle recently, OPM is so expensive.

Roger Bong: Who can afford these records?

Les Talusan: Yeah. There's a demand. There's a high demand now.

Les Talusan: That's what I'm saying. Our people cannot afford those records. I've actually written to a discog seller who was selling like a $2,000 compilation that I've wanted for a long time. Well, he, he lists a lot of stuff, but I told him to please block me because. I can't afford this. And like, who are you trying to sell to? You know, it's exploitative. I think it's, I don't know.

Arshia Haq: Yeah. I was just, I was gonna say there's so many thoughts that kind of came through my mind through the last few responses and about, well one, the invisibility of, of playlists and not naming everything, and while there's a part of me that also understands why it is good to name everything, then there's a little part of me that's … well then they're going to know our secrets and this is part of what the commodification is. And this is why the prices are this on Discogs. And, and so it's complicated and also totally agree with you Les, I actually posted on Discostan, like maybe a couple of months ago, just a proclamation that anyone selling records needs to give a special price for people if they're selling back to people of origin .

Les Talusan: That’s what I’m saying. I actually liked your post. I liked that post.

Arshia Haq: One person did reach out to me and sell me the record I was looking for at a reasonable price. So that was, there's actually a few people that have, you know, kind of responded to that. But it's very complicated. I was also thinking about how much we have to think about our identities. And Roger you thinking through so much and kind of the torture of do I have the right? You know, it's like, they wouldn't think about this at all. You know, they haven't thought about it at all. Historically, they don't think about it. Music from specifically from India and Pakistan, there's this interest and exploitation and self exploitation of that music. And so with the work that we do at Discostan, a lot of it is about just changing language to describe the music, you know, from the very basic things like “exotic” to also this thing about discovery, like unheard of, rare, like all these kinds of sensationalist words, even digging.

Les Talusan: Rare groove rubs me the wrong way. Rare groove absolutely rubs me the wrong way.

Arshia Haq: Digging is a problem, I think.

Les Talusan: I think it's funny. I think it's a funny term because I've heard it more from people in Japan and obviously English is not their first language. That doesn't bother me as much. I just think it's a funny term.

Arshia Haq: But it also has this connotation of being something that was hidden and not known, but it was known to so many people it's just, wasn't known to whoever has been the arbiter.

Roger Bong: I mean, I've got to admit, I don't put any tracklists up on our vinyl factory sets. The reason being I run a record label, and if I put any of this stuff out there, other people run record labels and they're doing re-issue work just like I'm doing, but there might be some labels out there that have way more resources at their disposal than I do to license this music before I get a chance to, and it's happened before. That’s for sure.

Roger Bong: But I would like Aloha Got Soul to be hopefully the label that helps to present a lot of this music. So that's just a disclaimer. If you check out my videos on the final factory, you won't see a playlist. I saw yours, Rochelle.

Les Talusan: I was gonna say, though, I was going to say that a lot of the times, like I recently have a sixties beat soul mix for, um, WFMU , and, you know, they put all the tracks there, everything, you know, and a lot of there's like $300 seven inches there that obviously I didn't get for that much. I don't mind that. But also on my radio show though, for Eaton , I don't always put out the track lists. Cause sometimes it's like, I do so much work already. Do some of the work, do a little bit of the work too.

Arshia Haq: Roger. I feel, I feel your pain about the resources and the… it's already happened by the way.

Rochelle Kwan: I know you just launched the label this year, right? Yeah.

Arshia Haq: Yeah. After thinking about it for 10 years and really thinking about it, you know, and, actually, I went to a bunch of other labels before we decided to do our own, to bring the records to them, you know, because I was just doubting, oh, I don't, they already have the networks.

Arshia Haq: They know how to do it. That, you know, I want to make sure the record gets the press it deserves. And a lot of people were like, “Oh, this, this isn't the sound. This is too this, too synth too femme.” And the record sold out within two months and then suddenly there's other people who are really interested in releasing that kind of sound. So, yeah, but it took a long time to just kind of get over that hurdle in my own head about what constitutes expertise.

Rochelle Kwan: Can you dig into that a little bit?

Arshia Haq: I think the idea of all of the disciplines, like ethnography, ethnomusicology even to this day, I would say came from a deeply racist place or at least in how things were framed.

Arshia Haq: And I think that still persists in the language that we see even today to sell records of other music. But yeah, it's, it's also just this idea of who decides what is worth listening to. This idea of expertise and power and institutions. And what did get exported from, from a lot of countries before until recently.

Roger Bong: I would love to say something about all of that.

Roger Bong: I've been running Aloha Got Soul as a label since 2015. And do you know our first year we did one record by Mike Lundy. And that was all we did the whole first year. And now we just finalized next year's release schedule. And we got like 15 different artists lined up for release. And to me, it's crazy. It's a lot of work. Beyond that there’s like 15 plus more records we wish we could release next year, but we just don't have the resources right now. But what I've learned is you do what you can do, even though I want to do it all. I know that I'm only one person, and I have the help of these friends whom I really trust.

Roger Bong: And we're going to do our best at what we’ve committed to doing. And then on top of that, what really matters to me at least, is sharing this music from the perspective from which I see and how it affects me personally. And I think that really resonates with others is the story that comes with the music, whether it's the artist’s story or my personal story, or just a story of say, Hawaii as a greater community and how that stuff is affected.

Roger Bong: But the one thing I really want, like you asked earlier, why should people care? Like why should people care about what we're trying to do? And I think the main thing is, is that we can prove, I don't even know if we need to prove, but we can show others that hey, this music is not kitschy. It's not provincial.

Roger Bong: It's not. It can actually stand up against all these great artists and great cities and music that's being created at quote unquote “high level of standards” that say you wouldn't imagine musicians from Hawaii being able to reach that level. But when you're able to throw something into a DJ set, for example, and people are like, “Wait a second. What is this?” And you're like, “Oh, this is from Hawaii. This is from India. This is from the Philippines.” But I think eventually I think one of the goals that I really want to achieve is to just show young people that this is possible. You can make whatever kind of music you want to make. You don't have to conform to anybody else's ideal of what you should be.

Rochelle Kwan: As somebody who just came into doing music through deejaying and cultural archiving just a year ago, I am not anywhere close to an expert, especially because I can't read Chinese. I can't write Chinese. So a lot of what I've been learning about the records are from my neighbors or from people who listened to this kind of music. And I still have a lot of feelings about like, I am not a DJ. I don't know how to mix. I just put one song on, and I put the next song on. And the whole time it has felt like this is not something that I have ever had to do alone. And so like I'm, I'm working on digitizing these records with my neigh— one of my neighbors right now, and she's in her eighties and taught her how to use Google Docs so that we can populate this written archive together because she reads and writes Chinese. So it's like the ways in which we've all been kinda doing music and exploring and sharing music has been about building and growing this community of folks who are interested in the music and also want to be a part of it with us.

Roger Bong: I need to shout out to my label partner, Vinyl Don, Don Hernandez . He does most of the mixes and like, you know, live streaming events and whatnot that Aloha Got Soul puts out nowadays. He could be a good example of someone who just found this music so close to his heart and just felt a need to, to listen further. He was born and raised in Los Angeles , spent some time in Hawaii with family on vacation and whatnot, but something clicked for him. And it's great because we can nerd out so heavily and just dive into these rabbit holes of music from Hawaii that you might not even know exist.

Rochelle Kwan: What is the significance of creating these spaces to share and celebrate music with each other, especially multi-generational because I think now the dance and music world can lean very young. And a lot of the history that comes with the music lies in older generations so where do you see your music and all your work coming in to tie all those together?

Les Talusan: So, you know, what's been happening with OPM Sundays? In the past, uh, in October will be our first year of streaming on Twitch, but I started streaming on Instagram in I think April. It has become a gathering place for elders and also kids. I mean, there are literally kids in the stream. They're like five years old. Like “I like this song,” you know? And, uh, they're Filipino American kids, you know? And then there's someone in the chat. Sometimes he would come in, Roger Rigor, who is one of the members of VST & Company and VST & Company is one of the most important bands that shaped the Manila sound.

Les Talusan: He comes into the chats. And, you know, he'll be like, oh, can you play this song by Jakiri ? I don't know. I just think it's important to create space, to listen and to just reminisce. A friend's mom was tuned in one time and he videoed his mom just singing along to like everything I was playing. And that was really sweet, but sometimes I don't always play like all older stuff, sometimes it's new stuff. So there are people there to get introduced to that stuff.

Arshia Haq: Yeah, for me, it's interesting because you know, also like Les, it's not just vintage music or older music. And even a lot of that music is actually stuff that I was listening to in my childhood, which has now become vintage, but there's also, for me, it's important to play new music from diasporas or even within the regions, how people are re reinterpreting this music or their sounds, you know, people now more and more sampling folkloric sounds for example, folk instruments into edits that they're doing or dance music in a way that’s informed from having inherited this music is, is all really important because I think nostalgia can actually be really dangerous, especially for people in diaspora.

Arshia Haq: It can be something that keeps you in the idea of a particular golden moment in the past, and then maybe not considering how things have evolved or grown or are still continuing to be rich and productive. And that's especially important, I think for conflict regions, because actually there's a lot of instrumentalization of nostalgia to justify invasions even to the present day of restoring to a certain time of, you know, when things were free here or there, or whatever. And yeah, so it’s complicated.

Roger Bong: I think for me and people, my age and younger, I think it's important for us to look to the past so we can situate ourselves in the present and, and build a future that we want to build for ourselves. But also, I just really appreciate when older musicians say to me, thank you for remembering us. Thank you for helping this music to live on. And it's, if that was the only thing that I was doing this for, I mean, I'm good. I can, I can retire from this cause it feels so good to hear that from your elders.

Les Talusan: Can I read you a letter? This is from Roger Rigor, who I was talking about, who is in VST & Company.

Les Talusan: He said: Dear Les, just a small token of acknowledgements for your unabashed initiative. We now see a clear spawning of a culture here in the U S that truly appreciates that, which was the seventies OPM era. Many will be grateful for your work, your vision and your dedication.

Les Talusan: I know we are. Carry on, mga kakosa sa musikang OPM — or like my mates in OPM music.

Les Talusan: And on behalf of the guys of VST & Company, maraming salamat, Roger Rigor.

Les Talusan: This is just like, it's so crazy because I just do things because I do them sometimes I don't think too deep, but when you get seen, that was crazy. I think it's like, you understand me?

Arshia Haq: Is that a handwritten letter?

Les Talusan: Yeah, it is. It's a handwritten letter. Put it here next to Jollibee.

Rochelle Kwan: Yeah. I think one thing that I was just tying all together from what you all just said is, especially what Arshia was saying about how nostalgia can, can get us stuck. And one thing that I really love about this work that I've been doing and being able to talk to my elders and my neighbors is that they lived through this music, what in its heyday, and now they're seeing me as a young person who didn't live through that and seeing the things that, that are coming from this music now and how it can continue on. To me, it just shows that we're not the only ones learning as young people. We're not the only ones learning from older folks, but older folks can also learn from us as younger folks.

Rochelle Kwan: And there is that exchange of knowledge and exchange of care in this work that keeps us moving forward rather than just going backwards all the time. I have felt that the whole time in doing this work. And so I'm really, really happy to hear that you all have those feelings of looking into the future as well, and really incorporating that into your work and bringing your communities, your identities, the histories into everything that you do. I'm just really excited to keep learning from you all as a very new DJ still, and just wanted to thank y'all for being here today and hanging out with me and meeting each other and just nerding out. Honestly.

Les Talusan: Thanks for inviting us, Rochelle.

Roger Bong: Thank you for this opportunity and, yeah great to meet you Arshia.

Arshia Haq: too. Thank you so much. I just had a question: Les where are you based?

Les Talusan: I am in Washington, DC. Yeah. So I moved to the U.S. in 99 to Maryland, like blocks away from the DC line. But yeah, I've been here longer than the Philippines. I got two copies of your first release, by the way, I sent one to my homie in the Phillipines.Cause I was like, you're gonna love this shit. Yeah. Same with, uh, Mackey Feary reissue. I got the extra to send to my friend in the Philippines.

Rochelle Kwan: Yay. Well, I have a record for you, Les. That I have three copies of.

Les Talusan: Oh my God. I can't wait. I can't wait. I'm going to see you soon. I swear.

Rochelle Kwan: Yeah, we'll come back for round two. All right, we'll talk soon.

Mix of voices: Take care. Bye bye!

Credits

CATHY VO: This episode was produced by Rochelle Kwan.

ROCHELLE VO: We were edited by Julia Shu and James Boo, with help from Sheena Tan.

CATHY VO: Our theme music is by Dorian Love.

ROCHELLE VO: Check the show notes for more details about the music and our DJs.

CATHY VO: Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Our Executive producer is Ken Ikeda.

ROCHELLE VO: This episode was made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts Creator Program.

CATHY VO: And of course, our listener community.

ROCHELLE VO: You can follow us on the socials at self evident show.

CATHY VO: I’m Cathy Erway. Let’s talk soon.

ROCHELLE VO: Until then, keep dancing!