Episode 002: The Non-United States of Asian America

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

Self Evident tells Asian American stories — but that term itself, “Asian American,” can mean many different things to different people. In this episode we present three stories from our listener community to explore the ways “Asian American” reflects both representation and exclusion, empowerment and stereotyping, under the diverse umbrella of Asian American identity.

Add your perspective:

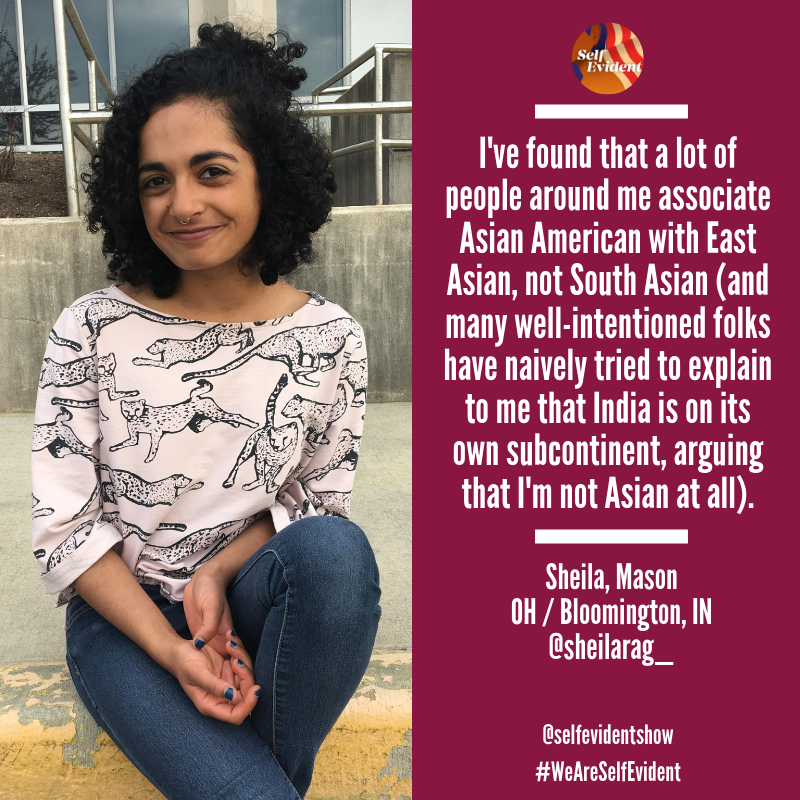

This episode was based on almost 100 responses we got from our community of listeners. We’d love to hear from you: Do YOU identify as Asian American? Why or why not? Email us a sentence or two sharing your thoughts (plus a photo of yourself, if you’d like) to community@selfevidentshow.com and we’ll make a graphic like the ones shown here to share on social media.

Episode 002: Bonus Interview

Sharmin Hossain, a member of New York’s Bangladeshi Feminist Collective, helps us take a hard look at the roles of class, colorism, and cultural education within the broader conversation about Asian representation in America.

Resources and Recommended Reading:

Key Facts about Asian Americans research from the Pew Research Center

“Who Is Vincent Chin? The History and Relevance of a 1982 Killing” by Frances Kai-Hwa Wang from NBC Asian America

Census Suppression podcast episode of “In the Thick,” with Hansi Lo Wang from NPR and Dorian Warren from the Center for Community Change, for more discussion about the upcoming Census

The Asian American Movement, a history book recommended by Marissiko Wheaton

Activist Amy Uyematsu Proclaims the Emergence of “Yellow Power,” a 1969 article recommended by Marissiko Wheaton

Shout Outs:

In addition to the nearly 100 community members who shared their perspectives with us for this episode, we want to give a special shout out to everyone who sent in voice memos and had conversations with us about how they felt about the term “Asian American”: Akira Olivia Kumamoto, Alana Mohamed, Andrew Hsieh, Julia Arciga, Kelly Chan, Maha Chaudhry, Marissiko Wheaton, Mia Warren, Nicole Go, Sharmin Hossain, and Veasna Has.

This episode was made possible by the generous support of Noah Berland and the rest of our 1,004 crowdfund backers.

Credits:

Produced by Julia Shu and Cathy Erway

Edited by Cheryl Devall

Tape syncs by Mona Yeh and Shana Daloria

Production support and fact checking by Katherine Jinyi Li

Editorial support from Davey Kim, Alex Laughlin, Managing Producer James Boo, and Executive Producer Ken Ikeda

Sound Engineering by Timothy Lou Ly

Theme Music by Dorian Love

Music by Blue Dot Sessions and Epidemic Sound

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

About:

Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Season 1 is presented by the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM), the Ford Foundation, and our listener community. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP.

About CAAM: CAAM (Center for Asian American Media) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to presenting stories that convey the richness and diversity of Asian American experiences to the broadest audience possible. CAAM does this by funding, producing, distributing, and exhibiting works in film, television, and digital media. For more information on CAAM, please visit www.caamedia.org. With support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, CAAM provides production funding to independent producers who make engaging Asian American works for public media.

Transcript

CATHY: I’m not sure when exactly I started using it - it just seemed like something that’s always been around us….

News clip: “this case against Harvard, alleging discrimination against Asian Americans, the case rest on …”

News clip: “making history as the first Asian American woman in more than 40 years….”

CATHY: The term “Asian American.” It might seem universal, but not everyone is happy about it.

Music: Self Evident theme begins

“I think for most people they associate Asian American with East Asians only and as a Pakistani American I obviously don’t fit that category”

“I tend to get more granular when I’m talking to someone who’s also Asian American”

“...but I just prefer to be more specific and use Cambodian American whenever possible”

“It was something that I got introduced to when I was applying for colleges”

“It was something I got introduced to when I started applying for colleges”

“His parents wanted an Asian Asian, not like a kind-of Asian”

Music: theme music continues in full

CATHY: This is Self Evident, where we take on what it means to be American by telling Asian America’s stories. I’m your host, Cathy Erway, and this season of our show is presented by the Center for Asian American Media.

But when we say Asian America's stories...who IS calling themselves Asian American, and why or why not? As a catch-all term for some 20 million people, it’s not a simple answer.

We know that this episode is only going to scratch the surface - and point to all the stories we can tell in the future. But to start, we wanted to take a closer look at why "Asian American" came to be widely used, and hear from people who've struggled to feel at home with it.

I thought we'd begin with our own team. So I asked one of our producers, Julia Shu, to answer a question we've been asking a lot of people.

JULIA: Hi Cathy!

CATHY: Hey Julia! So, do you call yourself Asian American?

JULIA: Yes, I do! Growing up, I would say that I was Chinese American… then in college, that's when I started saying Asian American. But what about you?

CATHY: So I’m OK with it, but I’m mixed. The way I see it, I have one American parent, one Asian parent. So it feels like an actual, literal description to say Asian American.

JULIA: yeah!

CATHY: It feels perfectly comfortable now but it’s something I’ve grown into over the course of my life, being half-Taiwanese… and that’s not something that people immediately recognize when they see me - people have these preconceptions about what “mixed race” looks like and that's not true.

But I’ve been involved with a lot of mixed-race groups…and Taiwanese American groups…and Asian American groups…you know, I’ve written a book about Taiwanese food, and I studied Chinese when I was studying abroad in Taiwan too.

JULIA: That’s really impressive… and if anything is proof that looks don’t mean anything - I don’t know ANY Chinese and both sides of my family are Chinese American!

CATHY: Right! … so it’s something I’m proud of.

JULIA: It sounds like Asian American identity is something that through your career you’ve really claimed. For me, it’s partly that I have family members who were active in the Asian American movement.

CATHY: Oh!

JULIA: My uncle was a young activist in LA. He grew up to become a lawyer and worked on the Vincent Chin case.

CATHY: wow Vincent Chin?

JULIA: yeah - it was a huge deal.

CATHY: Yeah, so for anyone who doesn’t remember the details, he was a young man who was murdered by white men who thought he was Japanese, but actually, he was Chinese American

JULIA: Mm hm, and it was a huge turning point for the Asian American movement -

Music: 80's music begins

JULIA: It was in 1982, in Detroit, and all these autoworkers upset about competition from Japanese cars

Tape: "...taking their frustrations out on this '78 Toyota..."

JULIA: People in Detroit were actually smashing up Japanese cars, they were so angry.

CATHY: Oh my god

Tape: thumping sounds continue "...the combat is never more real and symbolic at the same time"

JULIA: The white men who killed Vincent Chin yelled that he was the reason they were out of work -- and then they beat him to death with a baseball bat when he was celebrating his bachelor party.

CATHY: oh my god. And didn’t they actually have multiple trials?

JULIA: Mm hm, so at first they pled to manslaughter, and then activists, including my uncle, led an effort to prosecute them for violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights - so that was a hate crime. The result of all that, and what made people so angry, was that they never served any prison time, they just paid a fine.

CATHY: Oh my god. Yeah, so there are lots of cases in history of different Asian groups being pitted against each other, especially Japanese and Chinese Americans being forced to compete. But in this case, it really didn’t matter! The message was - anyone Asian-looking is in danger because white Americans don’t care about your ethnicity, they just assume you don’t belong.

JULIA: It was a huge reminder too for all Asian Americans that it's really important to have a collective voice to respond to injustice. So case in point, now my uncle, Stewart Kwoh, is the director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice in LA, and it's this non-profit legal aid, civil rights organization.

So, I decided to call him, and ask about when he first started hearing the term “Asian American”...

STEWART: I was at UCLA at age 18 and I think there was a sense of having Asian American studies rather than just Chinese studies. So I adopted kind of an Asian American viewpoint pretty early on.

I think the Civil Rights Movement was the key movement that moved me.

Later on, I read how the immigration law was changed in 1965 and the discussion was very much about civil rights… and so I realized that the African-American-led Civil Rights Movement had a direct impact on Asian Americans.

JULIA: Wow. Cathy and I were actually just talking about your role in the Vincent Chin case. How did you take it when the murderers got off with no prison time?

Music: slow, sombre music begins

STEWART: Well, I was certainly angry at the outcome. It wasn't unexpected, unfortunately.

I felt that we needed to build the strongest biggest civil rights organization possible We weren't able to go to the Detroit or the Cincinnati courthouse on a continuing basis. I think if we were able to have more presence, then people would pay more attention.

JULIA: So you mean just having the resources to travel to there might’ve made a difference?

STEWART: Yeah, we didn't have money to hire somebody to go to these places. So that was a problem.

JULIA: And so now that you’ve spent decades organizing…. raising money, like, building power for Asian American communities, what’s been the biggest challenge?

STEWART: Well, I always thought that Asian Americans was both a movement and a practical coming together because there were so many different ethnic-specific histories and cultures. You had to bring it together in some way without losing the specific identities. So that's always been kind of the tension as well as the opportunity of the Asian-American term as well as the Asian American reality.

Music

CATHY: Wow! Your uncle is a hero.

JULIA: and he’s also very good at fishing. But yes, he is! The conversation, first of all, just made me feel so appreciative of Asian American organizations today and all the work they do.

CATHY: Yeah, and that history really places the term “Asian American” in a powerful place, right? With the Civil Right Movement as a model, gaining political power by coming together against injustice. It’s like a coming of age moment for Asian Americans.

JULIA: yeah, and for me, that idea of unifying for civil rights, and knowing that my family played a role in it? That’s why I use Asian American to describe myself.

CATHY: But over the past few decades, there’ve been even more changes that expand who Asian Americans are, right? It wasn’t so long ago that Asians were banned from immigrating, but since then, with various waves of immigration from different parts of Asia, we’ve become the fastest growing demographic.

So, I wanted to talk to some folks who didn’t grow up knowing any of the stuff your uncle talked about to see how useful saying “Asian American” is to them.

Music: moderate beat starts

CATHY: These are young people who, if there was a survey, they’d fall under Asian American, but their personal reality is more complicated than that.

JULIA: So, this is a real test of the tension that Uncle Stewart brought up, you know? Having so many identities in one label.

CATHY: Mm-hm, so the first person I talked to is, coincidentally also named Julia!

JULIA: ok!

CATHY: Yep, Julia Arciga, she’s a 22-year-old and she was born in Manila, but moved to California with her family when she was just 5. And she quickly assimilated to her new home.

JULIA ARCIGA:I kinda just hopped on a plane and never looked back. I think that was a factor in me loving America, loving Starbucks!

CATHY: In Manila, Julia and her mom spoke Chavacano, a dialect of Tagalog. After the move though, as part of her assimilation, her mom enforced English-only habits at home.

JULIA ARCIGA: Because I never spoke it, I can’t remember any Chavacano anymore. I distinctly remember my mother when she would speak to her relatives back at home she would go into her bedroom and close the door. And I could kinda of hear, but I couldn’t understand because it was in Chavacano which I didn't remember.

So it was kind of odd growing up. I got the sense it was kinda a little secret box that you keep in a corner, that was the past for me, was kinda in that little box.

CATHY: With Chavacano, and the rest of her past, hidden in that box, Julia’s connection to Filipino culture faded. But although her English was perfect, she still couldn’t blend in the way she wanted to.

JULIA ARCIGA: I always thought the fair-skinned blonde haired blue eyed girl was so beautiful. And I really wanted to embody that kind of beauty but I couldn’t because of course, I’m just not that skin tone. That was such a huge struggle for me.

CATHY: The years passed, and for Julia, identity became a question mark. She felt distant from Filipino culture, unsure of how to reclaim something she’d left behind so long ago.

Until one fateful day, when Julia was a sophomore in college, and her boyfriend dumped her. Via Facebook messenger!

JULIA ARCIGA: It was finals week, I was crying my eyes out in my books, and I was like, I need to find something that will help me stop crying, because I need to study and I can’t study with tears in my eyes! So I was looking around Spotify, I was like, I have to listen to happy music. I stumbled on K-pop, and I was like what the frick is K-pop? I distinctly remember Girls Generation's "Catch Me If You Can." It was just a bunch of Asian chicks dancing, saying “I’m gonna find my heart” and I was like wow, these girls are so bomb! I loved it.

CATHY: wow!

Music: "Catch Me If You Can" by Girls Generation starts

CATHY: Can you tell me about the song?

JULIA ARCIGA: So it’s like this sassy, trappy song with really big beats, and in the video they’re dancing in the middle of this construction zone, like it doesn’t make any sense but that’s fine because you’re just listening to them, they’re finding their hearts, you’re finding yours! Of course I don’t understand Korean, but K-pop is really popular in the Philippines, so I was like yeah! I think that tipped the iceberg for me

CATHY: So how do you make sense of that, you’re not Korean or Korean American so why do you think this was such a big moment for you?

JULIA ARCIGA: I think it was such a big moment for me because it was so different, it was like nothing I’d seen, I think it was such a vague tie to anything, you know, Asian. I think I embraced that and ever since then I’ve found a K-pop community here, I go to K-pop events, and when I’m there it’s not just Asian Americans it’s people of all colors gathering around and enjoying K-pop for what it is, but I do also see a lot of Asian Americans. I think that’s one way I got my start feeling around my Asian-ness and embracing it for what it is. Yeah!

CATHY: Your Asian-ness now, yeah Do you say you’re Asian, or Asian American, now?

JULIA ARCIGA: I'm still kinda grappling with that. I kind of struggle with saying I’m Asian American just because when I introduce myself to people, I give the long-winded answer, oh I’m from Los Angeles but I was born in Manila. So I do like to identify as, I was not born in this country that’s why I’m this color, so you don’t have to do the follow up of, what's your ethnicity?

CATHY: What about Filipino American?

JULIA ARCIGA: I mean, I always shy away from those labels, I don’t think I would ever say that out loud or ever introduce myself as a Filipino American, I just feel too disconnected from the Philippines to just comfortably take that label.

CATHY: Do you know more Korean than Chavacano now, because of K-Pop?

JULIA ARCIGA: Probably, it’s kinda a weird thought but probably (laughs)

CATHY: So that’s where Julia is at now - not saying she’s Asian American, or Filipino American, just “exploring her Asian-ness” and figuring it out.

JULIA: Now I feel a great need to go listen to Girls Generation.

CATHY: Right!? Can we play K-pop for the rest of this episode?

JULIA: I don't know if we can afford the fees for the music.

CATHY: Aww. alright, fine.

CATHY: I do want to add that Julia sent us an email after this interview noting that as she’s gotten into K-pop more, she’s been thinking about the emphasis on “milky” pale skin, double eyelid surgery, colored contacts, which lots of people see as a way of mimicking white or Western beauty. So she said while K-pop is still the world that made her appreciate her Asian features, now she’s hoping for more darker skinned representation, as in, more Asians who look like her!

JULIA: Yeah, that’s a really good point. I mean, I feel like her story is such a powerful endorsement of representation because it’s true that K-pop stars actually look a little bit different from Julia in some ways. But still, seeing Asian women as these glamorous, badass stars was a huge change for her. It shows how a collective Asian identity can still make a difference even outside of political activism.

CATHY: Yeah, and on the flip side, collective identity doesn’t work when people don’t see themselves represented in the group. So next I wanted to bring up this comment from Maha Chaudhry, she’s Pakistani American, and she was one of the voices you heard at the start of our show:

MAHA: I think the only time I've really self-identified as Asian American is on government forms, I think for most people they associate Asian-American with East Asians only and as a Pakistani American I obviously don't fit that category. I also stray away from using the term South Asian. I'm super aware of the sacrifice my grandparents made when they migrated from India to Pakistan and I want to honor that sacrifice by being really open about my Pakistani identity.

JULIA: Wow, I can definitely second her statement about people associating Asian American with East Asians only. Like if you’ve ever been to an Asian American studies classes, a huge part of it is Chinese American history, like the Exclusion Act, the Gold Rush, the railroads… so as a Chinese American, I get to feel included. But that’s a focus that overlooks so many other identities.

CATHY: For sure, and that criticism could be made of Asian American organizations or Asian American media stories. It all goes back to what your uncle said about the tension of having so many groups in one term.

JULIA: So for the record, since Maha brought up government forms for the record, “Asian American” doesn’t appear on the US Census. You actually see individual boxes for, Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, and Samoan.

And then you get two other boxes that say “Other Pacific Islander” and “Other Asian”

CATHY: Hahah, “OTHER ASIAN?” I’d check that one.

JULIA: Yeah, well, then there's a space where you could write “Taiwanese American Mixed Race Show Host," there's space for that!

CATHY: (laughs) perfect!

JULIA: So, this is obviously a huge range of people, and that level of detail is unique to the Census -it’s taken a long time to get to have all those different identities listed out, and plenty of other forms just say “Asian” -- like if you remember doing a job application, there’s that survey at the end that says "Equal Employment Opportunity" where they ask, are you a veteran? do you have a disability? and that one, it just says "Asian," there's just one box.

CATHY: hahah. This is such a huge range and it shows how much variation there is just in filling out forms. And of course, none of that, even with the more specific categories in the Census, can account for class, religion…...or the other millions of factors that give Asian Americans unique backgrounds and identities. And then by default, when we erase those things, it means applying the same Asian immigrant myths to everyone.

JULIA: Yeah, the story that we came here for a better life, we study really hard, we work really hard, we're good immigrants

CATHY: We're good students...yeah. and that's something that really turned off the next person I spoke with from calling herself Asian American...at first.

BREAK:

CATHY: We want to hear your stories and keep this conversation going online. So, do you identify as Asian American? Why or why not? Email your story to community@selfevidentshow.com, or share with us on social media, @selfevidentshow, with the hashtag #weareselfevident.

Music begins

ALANA: Like are only so many definitions of like what it meant to be Asian-American that like I didn't really relate to you know. They're like there's this whole kind of script right that like your parents come here and they sacrificed everything and they're super strict and like super limiting and you feel like always out of touch with like American culture you have like one foot in like each door, I felt like growing up that didn't really reflect my experience.

CATHY: That’s Alana Mohamed, she’s 26, from Queens New York. Her parents immigrated there from Guyana, and she described herself as Indo Guyanese, because generations ago, her South Asian family immigrated to Guyana. And there was a lot of racial and cultural mixing - like for example, she says they would celebrate Christian and Muslim holidays.

And as a young kid in Queens, Alana was around a lot of other Caribbean families who understood that. But as she grew up, she started getting bussed to a different school.

ALANA: There were two other black kids on the bus and then one Indian girl. So we'd be on the bus like having a good time, but then you know, once we get off the bus and we kind of like self-segregated somehow. I remeber there was like a culture day, type of situation where you get to like bringing a dish from your leg culture. And so I brought in some bake and saltfish.

JULIA: Wait, sorry to interrupt but what IS bake and saltfish?

CATHY: Bake is a type of round bread, it's puffy, and saltfish is what it sounds like, fish that’s been cured with salt, rehydrated, cooked with onions, other spices, and you eat it together.

JULIA: sounds really good!

CATHY: (laughs)Actually Alana told us that she wrote an essay about bake, and the teacher crossed it out and wrote “bacon” instead! And of course…..Alana’s family doesn’t eat pork!

JULIA: (laughs) oh no! It’s funny but also just sounds like such a classic immigrant food moment

CATHY: I know right? So when she brought this to class….

ALANA: Kids weren't really into it and my Indian friends were like, sure but no thank you And so like I had this like whole bowl of like saltfish and all these bakes and then I like boarded the bus back home.

CATHY: Aw

ALANA: And all of a sudden all the kids who were like familiar with the Caribbean were like, oh you have saltfish and they just like dug in.

CATHY: So growing up, Alana identified on this cultural level with her black Caribbean classmates, but knew that everyone saw her as Asian American - and she was starting to feel really resentful of the assumptions that came with that. Like when she felt forced to put “Asian American” on college applications --

ALANA: They always ask you that question was what's your race? I always had to check Asian-American even though I felt like it didn't really describe the way I was brought up or cultural values of like being Guyanese. There's like a lot of talk of respect for parents in this kind of like slavish way. There's like all this repression. There's all this kind of like dedication to testing and things like that. That seemed like such a small part of what Guyanese culture was to me.

CATHY: The disconnect between being seen as Asian American and not feeling that way -- grew even wider when Alana went to college at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Away from the relative diversity of her New York childhood, college was... a painfully white environment.

ALANA: I remember it was like the first week of classes, and this girl I did not know who lived across from me in the dorm, she just burst into my room, I didn’t know her at all and she just looked at me, grabbed me, pulled me into her room, sat me down in front of my computer and she said “do my marine biology homework, You look smart”

Music: slow music starts

ALANA: You know we talk about otherization and it can sound like just a word, but once you don’t feel like yourself you kinda lose your identity. For me it just made me so so depressed. I think at one point I was hanging out with these like, bad kids in their dorm and they were blasting music and drinking beer and I had to go see an alcohol counselor. And there’s this survey they make you fill out and one of the questions was “Are you depressed?”

And I was like, maybe I can say it here. Cause it was me and the computer, I didn’t understand the answers would be fed to the alcohol counselor. And there was one that was like, “Do you think about killing yourself?” And I quietly checked the box "yes."

And she called me in, and was like “are you ok?” and I had to do this thing where I had to publicly admit all these feelings.

CATHY: The trauma of racism threw Alana into crisis. But then, the college experience showed her another side to her “Asian American” identity. Alana read about all the people before her who’d experienced the same problems, both black and Asian -- including W.E.B. Dubois, who coined the term “double consciousness.” He was talking about the split identities black Americans navigate. Between the outside: how society sees them. And the inside: how they see themselves.

ALANA: It helped give me this language to see that the problem wasn't me. Because I think for so much of my time I was trying to like push through like whatever veil separated me as I saw myself from like the way people are treating me. Like somehow I can show them that I'm like this funny brilliant person worthy of like actual human interaction.

Just knowing that it's something that other people experienced helped me leave that idea behind, that there was something deficient in me.

It was so strange, I saw all this material as a lifeline, I was clinging on to it for ways to explain what I was feeling, ways to deal with what was happening to me.

CATHY: That lifeline, learning about past civil rights activists and organizers and feeling the connection between Asian Americans and other people of color, was what finally made Alana comfortable with the term.

ALANA: I identify much more loudly as Asian American than I did, I think before I was doing it kinda resentfully. But I still like to specify that I’m Indo Caribbean, because I feel like it’s important to acknowledge that just because you don't come straight from, you’re not directly descended from Asia doesn’t mean you’re not Asian American, so it’s important to acknowledge the diversity of experiences within the Asian American community.

Music: beat speeds up

ALANA: In some way it’s not up to us, but it’s like what do we do with this label that we’re given?

CATHY: So Julia, what do we do with this label that we’re given?

JULIA: (laughs) That’s such a huge question! Of course, this will be different for everyone but for Alana, she took this label and she kinda turned it into something that works for her.

CATHY: Yeah! Alana started off seeing “Asian American” as a term that just represented everything she didn’t want to be seen as - but when she was able to bring it back to what your uncle was talking about, how Asian Americans are linked to other communities of color, and the legacy of that history, it really hit home for her.

JULIA: yeah, we didn’t talk about it, but I wouldn’t be surprised at all if Uncle Stewart was reading duBois in college too.

CATHY: me neither.

JULIA: That also makes me think of this trend so far, which is that Julia and Alana, and my uncle! Mentioned exploring this identity while they were in college - and plenty of Asian Americans, or people who find themselves being labeled that way, didn’t go to college.

CATHY: Yeah good point! And I think that’s another perspective we’ve yet to cover.

Or maybe they were educated in another country, because my mom went to college in Taiwan and she lives in America now, and I bet her story around calling herself Asian American is different.

But for where we started this conversation, talking about the 60s and 70’s and student movements, I think it’s a natural focus because college campuses have been places that give Asian Americans academic knowledge AND a history of activism. That's why I decided to talk with someone who’s been researching Asian American student activism at universities.

CATHY: Marissiko Wheaton is a PhD candidate at University of Southern California, writing her dissertation about student resistance on college campuses. And how it connects to racial identity.

CATHY: Do you currently identify as Asian American?

MARISSIKO: I identify...yes, I identify as Asian American more politically than racially. I am ethnically mixed with Japanese and African-American. My experience is one of a black American I certainly identify politically with the Asian American term in terms of its political history, but I don't proclaim to have that experience racially.

CATHY: I see, tell me a little bit about what it was like growing up and how that's affected your take on this.

MARISSIKO: So both of my parents are actually black. My mom is half Japanese. My grandma is from Sendai Japan she, you know, was an immigrant here she came here after the war and so I grew up with her in the house until I was about 13, 14 years old.

Outside, externally like I really lived the experience of a black, of black American but I would say that when it comes to a lot of my values a lot of the ways that I was raised, you know, my grandma had a huge influence. A lot of the microaggressions that I've experienced have been often times related to being part Japanese or because of the fact that I don't racially look Japanese, I oftentimes hear really problematic statements about you know, Asian people the typical exoticizing statements. And so I hear those things and have to oftentimes decide am I going to respond to this or am I just going to let it slide? What is my position in all of this?

I always tell the students that I'm working with them sort of like an Insider/Outsider researcher, right? Like I'm a part of the community, I'm in solidarity, I have a familiarity and relationship to this work, but I'm an outsider in the sense that I never was really engaged as a student in Asian-American activism.

CATHY: Ah ok, so not something you participated in yourself when you were an undergrad -- but now, as a grad student in your research, would you say that Asian American students are more or less politically active?

MARISSIKO: That's actually what I'm trying to explore. It's really hard to compare whether or not a community is more or less politically active and the reason for that is because resistance and organizing and activism just looks, it can look so different right like, me asserting that my name is used properly to a tenured professor that could be seen as very political right and also the traditional route right like coming together as a community and protesting in front of the administration building.

Asian American students oftentimes feel very challenged with how to situate themselves in the discussions about race because we don't teach Asian American history the way that we should in schools, there's sort of a detachment to the history.

CATHY: What do you think is something that we should know our should be teaching?

MARISSIKO: I think it's just really important to talk about a lot of the ways that Asian Americans have been involved in other movements. We are so interconnected to every other community, right like we are a community of immigrants. We experience a type of racialization that is not the same by any means like African-Americans but similar to the one drop rule when you think about the way that Blackness is treated and othered, that anti- Asian sentiment is very similar in that we don't blend in when we stand in a crowd, right, that perpetual foreigner idea is still very pervasive.

CATHY: Right, and that experience of being other'd can be unifying just as a means of survival. But we’re also hearing that Asian American history and identity have been dominated by East Asian voices - like, Maha, one of our listeners, she told us that she always says “Pakistani American” instead of Asian American for that reason. So, on a related note Marissiko, what do you think about the term Asian American Pacific Islander?

MARISSIKO: Every single student that I interviewed in my study, including Pacific Islander students I said, What is your relationship to the term Asian American and every single Pacific Islander students said I have no relationship to the term Asian-American.

It's dangerous to attach Pacific Islander to Asian American and the reason for that is because there is a complicated history.

What ends up happening is that you know Pacific Islander communities suffer because they are being placed in the same category with Statistics that don't represent their experiences. They're indigenous communities they're - it's impossible to place them in the same category.

Oftentimes when we say API, we're really talking about Asian in the same way that you know, you know, Desi Americans might say when you're talking about Asian-American you really talking about East Asians, you're not talking about us

The activism itself looks very different. Right like the issues that they're fighting for are very different. The South Asian students are talking about their first memories of being politicized as children after 9/11 had happened. And Southeast Asian students are doing tremendous work within communities around refugee experiences.

CATHY: You know, your research really echoes this broader movement to, like, change the conversation about diversity in America to be less simplistic…. and more specific ... So. What does this mean for the future of the term "Asian American?”

MARISSIKO: I do think that it's going to continue to be relevant until we either politicize another way of thinking about this community or until there's another set of categories that we can go by, beyond just the basic ethnic identity.

CATHY: Individual.

MARISSIKO: Yeah.

I mean I I have I would imagine that Asian-American is going to become outdated at some point. It's just too broad.

Right like I mean, it's too broad. There's way too many languages and cultures and histories and all that stuff under this umbrella. And that's not to say that Latinx and black don't also have very diverse communities. But of course those have different relationships and so I'm not sure I think - I mean people still use Oriental which I find fascinating.

CATHY: (laughs) We're just saying, we were like brainstorming. It's on a lot of food things like Oriental flavor still.

MARISSIKO: Yeah. Yeah, I mean and you know, I think my grandma still uses that term, right? Yeah, I think it's just it's really like a generational. It's a generational thing. Right? Like we didn't stop using Negro or you know colored until we had a different politicized term to replace that and so I'm not sure.

I'm really I'm really interested to see what terms will become popularized.

CATHY: Yeah, who knows?

MARISSIKO: I do have to mention that. Maybe like a couple of years ago when Latinx like, you know, the gender neutral aspect became a thing sort of like in academic spaces. There were a ton of my like family and friends and people who were like sort of close to me were like, oh that term was - it's never going to get caught on like that's not, no one's going to say la-tin-x like and now I just find it interesting that like, that's really it's actually becoming like normalized and I'm so happy because it shows that when you do come up with something with a term that has purpose, that has political sort of meaning and that people can understand how it tangibly affects people's lives that we do adopt them. But the things that don't catch on or the ones that don't have that same substance.

Music bump

CATHY: So Julia, does this affect how you feel about saying Asian American?

JULIA: mmm. Do you think it’s too late to choose an easier topic for the episode?

CATHY: (laughs) I kinda think that ship has sailed.

JULIA: Well to be honest, the weird thing is that I’ve wanted to work on an episode like this for a long time, like before Self Evident existed I used to write down ideas for what I would put in it. But then when it comes to actually trying to pin it down, it’s so much harder because there’s no way to really cover everything.

CATHY: I know! But despite that, I think there are some common truths underneath the term Asian American that we were able to look at through these stories.

The first being the history of the term, how it came from a necessity for unity, for Asian American civil rights inspired by other activists of color. And for a lot of people, there’s still a need for pan-Asian community and belonging.

JULIA: And whether or not you find that in K-pop is up to you!

CATHY: Right! But this is what laid the groundwork for us to talk about Asian American representation... in media, Asian American politics, even Asian American podcasts!

JULIA: Yeah.

CATHY: At the same time, I think we have plenty of evidence that the same picture of Asian America that we’ve had for so long is not accurate anymore.

JULIA: Yeah, like in Alana's case, the label “Asian American” at first was defined by other people and by stereotypes. Or for Maha, by exclusion.

CATHY: Exactly, and just to echo Marissiko - it’s the substance behind the label that matters. We need to redefine what Asian American means for ourselves. My guess is that saying “Asian American” will keep some of the old meaning, but gain all these new dimensions from the voices we’re hearing today.

That’s why we have to keep asking people and sharing their stories -- because I think when we have that more honest and full picture of the Asian American experience, that’s when we can start to think about what we need in the future.

JULIA: Yeah, I still have no idea what that new term might be, but it sounds like we just have to keep listening. What you just described is really the work of a lifetime

CATHY: Yes, but luckily we’re not the only ones doing it! At the very least, we can do more stories about this in the future.

JULIA: Yes! I’m on board with that. Thanks so much Cathy.

CATHY: Thanks Julia.

CREDITS:

CATHY: Next time on Self Evident: One man’s mission to reconnect with his parents changes how he sees himself, and his heritage, forever.

Gabe: And whenever I have company around them, I see they’re charming and funny and decent people. And then we eat, and it’s silence. And I wonder why.

Fran: The alienation that you feel from Filipino culture, from your Filipino heritage, and the alienation that you feel from your own parents and family… what do you think the relationship between those two is?

Gabe: I almost feel like they’re the same thing. That’s, like, the big question.

CATHY: This episode was produced by Julia Shu. And me, Cathy Erway. We were edited by Cheryl Devall and mixed by Timothy Lou Ly.

JULIA: With production support from James Boo, Kat Li, Mona Yeh, and Shana Daloria. Our theme music is by Dorian Love.

CATHY: We want to hear from you! So let us know what you thought about this episode on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, @selfevidentshow.

JULIA: You can also e-mail us your thoughts at community@selfevidentshow.com.

CATHY: Help us get the word out by recommending this episode to your friends, family, and co-workers. You can also help us out by rating and reviewing us on iTunes, or wherever you’re listening.

CATHY: Thanks to our amazing advisors and all the members of our community panel who gave us feedback on this episode before it aired. If you want to be a part of our storytelling process, or if you want sneak peeks and behind-the-scenes content, sign up for our newsletter at selfevidentshow.com.

JULIA: We want to give a special shout out to everyone who sent in voice memos and had conversations with us about how they felt about the term Asian American:

CATHY: Akira Olivia Kumamoto

JULIA:Alana Mohamed

CATHY: Andrew Hsieh

JULIA:Julia Arciga

CATHY: Kelly Chan

JULIA: Maha Chaudhry

CATHY: Marissiko Wheaton

JULIA: Mia Warren

CATHY: Nicole Go

JULIA: Sharmin Houssain

CATHY: Veasna Has

JULIA: And of course to Stewart Kwoh

CATHY: And a very special thank you to Noah Berland and the other 1,004 crowdfund backers whose support made this season possible.

Self Evident is a Studiotobe Production. This season is presented by the Center for Asian American Media, with support from the Ford Foundation, and you! Our listeners. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP.

We’re managed by James Boo and Talisa Chang. Our Senior Producer is Julia Shu. Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda. Our Audience Team is Blair Matsuura, Joy Sampoonachot, Justine Lee, and Kira Wisniewski.

I’m Cathy Erway. Let’s talk soon! And till then, keep on sharing Asian America’s stories.