Episode 018 (Bonus): How Do We Go Beyond Representation? Feat. Eliza Romero, Marvin Yueh, and Thomas Mangloña II (AAPIHM 1/3)

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

We often take for granted that “seeing people who look like us” — especially in mass media — means progress towards racial justice. But what forms of representation do we see making an impact? And who is that impact for?

In this first episode of a three-part series, Senior Producer Julia Shu invites Eliza Romero (co-host of Unverified Accounts and blogger at Aesthetic Distance), Marvin Yueh (co-host of Books & Boba and co-creator of the Potluck Podcast Collective), and Thomas Mangloña II (journalist and co-founder of the Pacific Islander Task Force at AAJA) — to question conventional wisdom and share what kind of representation we want to see more of.

Our team decided to host these conversations because in the U.S. it’s once again Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, a time that can often feel routine and repetitive. And during a year when absolutely nothing has been routine, we hope these episodes will join many other podcasts, panels, and events in shaking up the usual talking points of representation, diversity, and inclusion for AAPIHM.

More From Today’s Guests:

Eliza Romero — @aesthdistance1 (Twitter), @aestheticdistance (IG)

Listen to “The New Asian American Class War” by Unverified Accounts (now merging into Escape From Plan A)

Marvin Yueh — @marvinyueh (Twitter), @marvinyueh (IG), happyecstatic.com

Listen to recent episodes of Books and Boba from the Podcast Potluck Collective (@podcastpotluck on Twitter and IG)

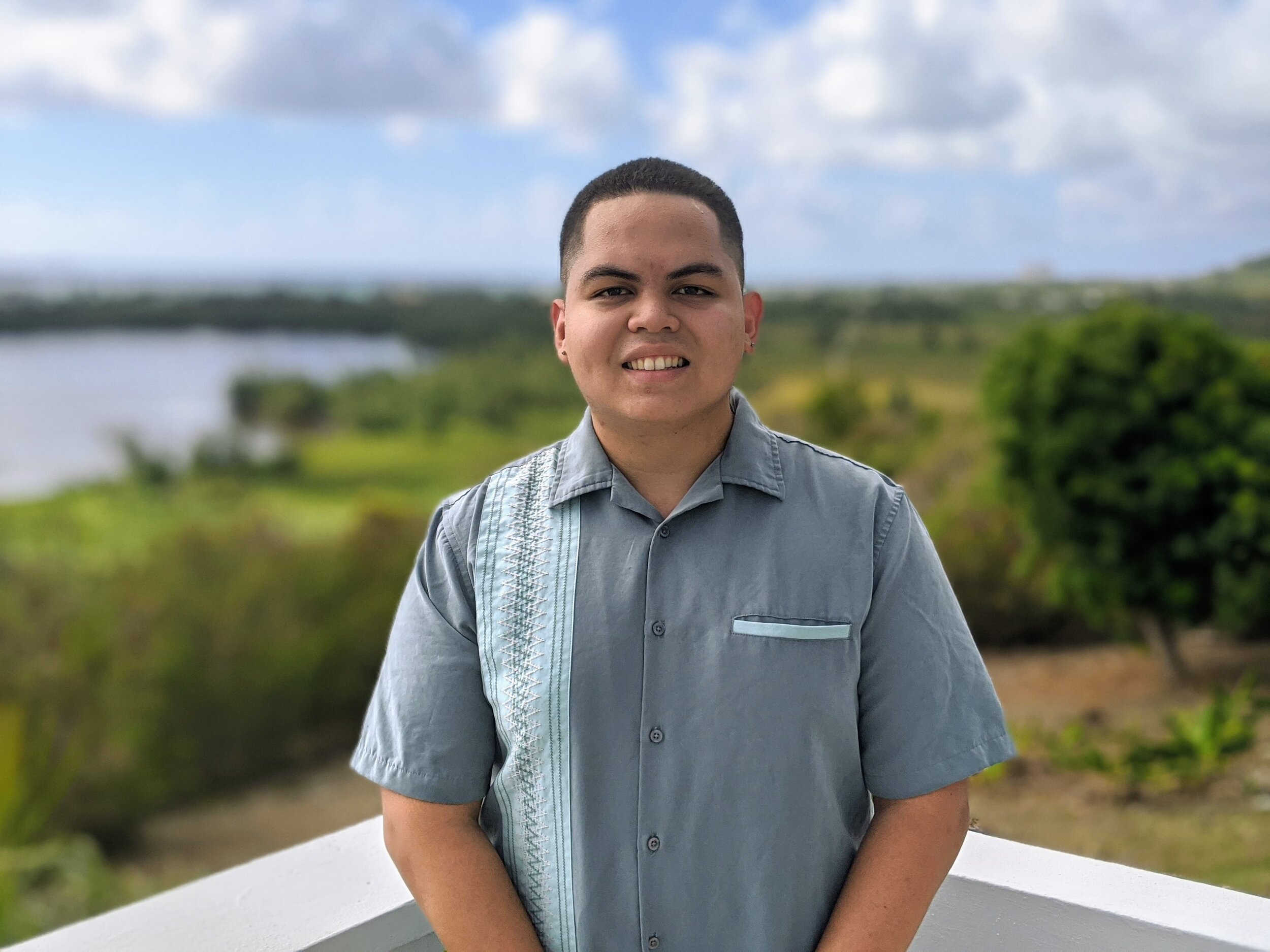

Thomas Mangloña II — @thomasreporting (Twitter)

Credits:

Produced by Julia Shu

Edited by Julia Shu and James Boo

Sound mix by Timothy Lou Ly

Self Evident theme music by Dorian Love

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

Self Evident is a Studio To Be production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts creator program — and our listener community.

We also want to give a big thank you to Wanda Ikeda, one of our biggest supporters on Patreon, for helping us keep all the lights on this month! You can help make our work sustainable by becoming a member at patreon.com/selfevidentshow.

Transcript

Intro

THEME MUSIC begins

Julia: This is Self Evident, I'm Senior Producer Julia Shu, filling in for our host Cathy.

Julia: You probably know that this month is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. And if you didn't know, maybe that's because you didn't open Netflix to see their current splash screen that says "Our voices, our stories."

Julia: Even Target has a section highlighting Asian business founders, quote, "Honoring the heritage behind the products and brands."

Julia: Since we're between seasons of the show, we decided to put together three bonus episodes this month, which are conversations that hopefully go a bit further than just celebrating our heritage.

Julia: With this three-part series, we wanted to challenge some of the usual assumptions about media representation, try to spell out the kind of change we think is really possible through storytelling, and have some real talk about what it's like to break away from a mainstream media company — or stay in that company and fight to make it better.

Julia: In today's conversation, we're questioning the basic messages we hear all the time, but especially during May — that representation matters, and that when we see and hear people who look like us, we're seeing progress towards racial justice.

Julia: So... who gets left out when we celebrate this month? What forms of representation do we see making an impact... and who is that impact for?

Julia: I brought in a few folks from podcasting and journalism, to talk about the limits of the media that we're consuming and making — and share what kind of representation we want to see more of.

Conversation With Eliza Romero, Marvin Yueh, and Thomas Mangloña II

Marvin: Hi, my name is Marvin Yueh. My pronouns are he/him. I am a freelance podcast producer, and I'm also a co-founder of the Potluck Podcast Collective — a collective of Asian hosted podcasts. My primary show, which is Books and Boba, it’s a book club podcast for books featuring authors of Asian descent.

Eliza: I'm Eliza Romero. I'm a blogger at Aesthetic Distance. I'm also a co-host on the Unverified Accounts podcast, along with Chris Jesu Lee and Filip Guo. And I'm also the Baltimore spokesperson for Maliah movement.

Thomas: My name is Thomas Mangloña. I use they/he pronouns. I'm currently calling in from Muwekma Ohlone territory at Stanford University, where I am pursuing my masters in journalism. I'm a video and television reporter and have worked in Guam and the Mariana islands. I'm also one of the co-founders for the Pacific Islander Task Force under the Asian American Journalists Association, seeking to increase representation and coverage of Pacific Islander communities.

Julia: Okay, so we're doing these conversations during May, which is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

Julia: So just to start off, I'm curious what that title means to you.

Thomas: So I'm Indigenous Chamorro from the Island of Rota, in the Northern Mariana islands, which is a U.S. territory. And it wasn't until I moved to California, for my undergrad in the Bay Area, that I started identifying even as Pacific Islander. Back home, I identified more as Chamorro or, you know, a local on the Island. And it wasn't only until coming to the continental US where the term AAPI, for me, was a part of my vocabulary. And what I've come to learn now, after being here for five years for school, is that oftentimes this month is hurtful for Pacific Islander communities because of the erasure that happens. But I think that I want to borrow some words from a friend and mentor of mine, Tavae Samuelu, who's the director of EPIC (Empowering Pacific Islander Communities) who says that API is race-specific, but it needs to be anti-racist. And for me, what I hear when Tavae says that, is that while there is erasure that is valid in how many AAPI organizations efforts, social media campaigns, whatever it may be, exclude specific Islanders, there's also something to be said about how there can be a place of abundance and love to come from in terms of the solidarity there as well. And so I've seen a lot of Pacific Islanders claim this month as the time to put our stories, our narratives, our people front and center, trying to disrupt the AAPI term. I've also seen a lot of Pacific Islanders find common ground during this month and understand and seek to understand how we can work together as Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the vastness that both of those communities have.

Marvin: Yeah. I think something that you have to learn along the way is that AAPI is not a cultural identity, right? There is no, there's no real AAPI culture. AAPI is a political identity. It's a coalition of different cultures that come together to pool power. And that's where the term AAPI originally came from. So before I was a full-time freelance producer, I worked for Collaboration, which is a national nonprofit that supports Asian American creatives. And we produced talent shows across the nation. And so I was able to travel to a lot of different communities within the continental United States. And the Asian American, or AAPI consciousness, is fragmented by geography, by education.

Marvin: The things that we're talking about in, say, LA or New York, are different than what they’re talking about in, say, Dallas or Arkansas or the Midwest. And a lot of times it's because there's no.... like, the distribution of education or representation is not there. Not a lot of people have ever taken Asian American studies because it's just not widely available, right? There are only a couple hundred schools [that] even provide a class in Asian American studies, and they're mostly on the coast. So there's this disparity in just the consciousness of what the term AAPI means and because our community is just so representation-starved all the time, we take whatever is given to us, and we kind of claim it, and I think that's what causes the erasure, because it's such a nebulous term. We all try to claim it for ourselves, and we kind of forget that it's not an identity, it’s like a coalition.

Thomas: I think when I think about APAHM and the label of American, I'm also very cognizant of the colonial and violent military history and imperialistic history that Islanders have had to gone through. My home islands alone went through waves of colonization by the Spanish, Germans, Japanese, and the United States. And so even when we're trying to address issues within the Pacific Islander community, it’s especially important to notice how it's also very much a global struggle and international struggle. I come from a US territory, but I still don't feel as comfortable identifying as fully American. And so I think about this month and how a lot of the tension I think is also because under the US-centered approach of diversity and inclusion in a lot of these spaces, my Pacific Islander identity is put at the forefront by other people. And, you know, there are ways that I've felt almost forced to lead with that, but I'm also queer. I'm also non-binary. And there are ways that those identities even within the margins itself are experiencing their own struggles and successes.

Julia: Yeah. I feel like growing up, I didn't think about May being very special at all. I mean, May is when my birthday is. And so as a kid, I was excited about that, and not really conscious of it being this special heritage month until I went to journalism school. And then the more that I spent time in the world of media, the more I realized that it's this time when news organizations are like, “Great! Now it's time to post our Asian articles.” And I guess that's when it first became in my awareness as something that was happening, that was a big deal in some places.

Marvin: Yeah. I mean, APAHM has definitely become, like most things in the United States, commercialized. It’s, you know, it's a holiday now, and it's easy to say that we're tired of APAHM, but the truth is the visibility that it creates is still needed. I mean, I'm lucky to say that I live in LA where APAHM means events literally every single day, right? But for some communities, that’s not the case and APAHM is their chance to convince people in their communities to give a crap about Asians and Pacific Islanders?

Marvin: I think, you know, it goes back to what I was saying about how the Asian American identity consciousness is fragmented across the nation. And there's a lot of different ways to look at it, right? Like strategically, this is a time when the attention is on us, so for corporations under capitalism, everything is assigned a value and decisions are made on whether things will create value or not. And for this specific month, for some reason, Asian stuff is just valued more, so they're more likely to be given the budget, the resources to become something, right?

Marvin: And practically for us as creators, this is the time when it's the easiest to pitch work to clients for them to, quote unquote, “fulfill their diversity duties,” right?

Julia: That's such a real tension of like, it feels kind of gross, but at the same time, it's like, well, we have this advantage. So how can we use it? Eliza, what do you think about Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month?

Eliza: It's actually confusing.... the name itself. I don't understand why Asian American and Pacific Islander got crammed into the same month together. When they are not the same thing at all. I don't know anyone that calls themselves AAPI, which is something that I believe Marvin pointed out.

Marvin: Yeah. I mean, I've heard people refer to themselves as AAPI, but they are usually older.

Eliza: Right. I mean, I've gone through my whole life saying that I'm Filipino, so yeah. Personally, it doesn't matter in my own life because as I've become an adult and understand what this month is really for, it is for non-Asians to value Asian culture.

Eliza: It is like checking off a box for non-Asians, and one of the things that I did this year was, my kids are very young, and I signed them up for an Asian American history course. It’s a year-long course that they took and it's for seven to nine-year-olds. And for my older child, there's a section for nine to thirteen-year-olds.

Eliza: One of the reasons I signed them up is because if I wait for the school system to teach our own history, they’ll have to wait. They’ll either get a two-day project for APAHM or they'll have to wait until college and they have to take a specific class like Asian American Studies 101. And I don't think that there's any reason why they have to wait that long to study Asian American history.

Julia: Yeah, that's cool. I did not have any classes like that when I was a kid. For sure.

Eliza: Yeah. So I guess what I'm getting at is that I've been celebrating Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders the whole year, so this month doesn't mean anything for us.

Julia: Right. The other thing that I'm thinking about is that we've spent like the past few months reeling from all these extreme cases of anti-Asian violence. And then during the pandemic, especially Pacific Islander communities and lots of low income Asian communities have been hit really hard by COVID. And so all of those things coming together, then I'm like, okay, does this month have any other particular meaning or does it just put all of this pressure on us during May? We're all recognizing that the way this month works is that it's mainly for people who are not Asian and not Pacific Islander.

Thomas: In my experience, if you're a Pacific Islander in that public sphere, you're going to be tokenized a lot this month and asked to be kind of the only voice in the room for a community that is so vast.

Marvin: I think what bugs me the most about Asian Pacific American Heritage Month events is we're saying the same things over and over. Over the last few years, the conversation hasn't really progressed that much, right? We're still talking about how we need to have pride. We need to agree that diversity is good for the nation. And I think over the last few years, we've established that fact, right? So the conversations during this month should be talking about things like how do we fight institutionalized racism and bias? How do we decolonize? How do we unlearn the things that are holding community back instead of just paying lip service and going surface level. For better or worse, because of this month, our issues and our identity become hyper-visible.

Marvin: So this is the best opportunity for us to advance those conversations, but I don't really see that happening in a lot of the more mainstream events that are going on.

Julia: Yeah. Why do you think that is? That’s a big question.

Marvin: There’s a lot of reasons. It's hard to speak up, right? It's hard to be the first person to speak up. Because we're a capitalist society, people are concerned about their futures, right? The people in power, the people making decisions, the people giving money, the people that are in charge of our futures are still mostly the same people that have been in charge of this country since the beginning, right? White male generational wealth-holders. There's still that tension of, like, I believe these things. I want to shout these things. I believe these things, but I don't want to be the Vanguard, right?

Julia: I think also a fair answer to the question that I just asked is also like, well, what we should do is just ignore everything, and we should just live our lives and be happy in the best way possible, because if it really is for people who are not Asian American or not Pacific Islander, then, you know, like why should we care, basically?

Eliza: I don't think that the month is harmful in any way or does any damage. I just don't think it's for me, you know?

Marvin: Yeah. And I think part of that is also, I mean, for me personally, I have the privilege of living in LA and San Gabriel where I am amongst an Asian American community. I think for me, seeing friends who were like coming to their own, who did grow up feeling ashamed or feeling conflicted about their Asian-ness, it hurt me. It made me feel real bad, and I wanted to do something for them. And I think that's where the inspiration comes from.

Eliza: It's very similar to my own experience. Growing up, and even now, I'm surrounded by Filipino family members. Now that I think about it, I think all my friends are Filipino or some sort of Asian ethnicity, so I don't feel isolated in any way. The month to me, it doesn't empower me in any way or uplift me. But I'm sure it does for some people. And I can respect that.

Thomas: Yeah, definitely. As you were saying, I think we've all touched on it a little bit, it's a focal point. And I think in talking with Pacific Islanders or panels for campaigns this month, it’s a time to take the center stage if it's offered for some people. I also think a lot about what Marvin said. It depends where you're at. I opened up with saying that I was on Ohlone land because I know that for a lot of Pacific Islanders, especially in the diaspora, it's really important to especially listen to our Native American family, wherever we are. Because even as indigenous Pacific Islanders, when we are not on our indigenous lands, we are on someone else's indigenous land.

Thomas: And so that's also something I wanted to rope in because even with organizing within the AAPI umbrella, and this is something I experienced in undergrad as well, some Pacific Islander students preferred to be identified as Indigenous. And in solidarity with Native American communities. So, where you are definitely is really important.

Julia: Yeah. You said to take the center stage if it's offered for some people. Who do you think the idea of AAPI heritage month just completely leaves out?

Thomas: Pacific Islanders. I mean, take a look, right? If we're going to talk about commercial media, take a look at all the different AAPI playlists or video series. There's a good chance you won't see one Pacific Islander on there. And so for me, I look at the month in terms of a community cultural organizing. I've heard a lot of my friends, also in organizing spaces, talk about if this is to raise awareness, it's worth it to let someone know simply where we are on the map.

Thomas: As another mentor of mine, Terisa Siagatonu, who's a poet, points out in one of her poems, when you look at a map of the world, it splits the Pacific in half, but in reality, the Pacific is one of the largest bodies of water on this earth. And so I think of Terisa’s poem. It's such a great description of what this month might be. To piece together that map for other people to see.

Julia: Yeah. So when people say, quote, “representation matters,” what do we assume is happening? Like an Indigenous actor is cast in a movie? An Asian director has won an award? What do you think that chain of events is?

Thomas: On the surface for me, I think what that means is visibility, especially with Indigenous communities, Pacific Islander communities, there is still that sense in general… public thought that we are extinct, take a look at any data or racial categories in any story and Native Americans, Pacific Islanders would be left out without a thought. When I think about visibility, I also get frustrated when people think that Moana, Jason Mamoa, and The Rock are the only three Islanders who exist in the world. Now I can have that tension, but still I cried when I realized that my little sister, one of the very first Disney princesses she will ever see was Moana.

Thomas: So for me, I can live in that tension. The idea that, well, why not isn't all of us and that there were problems with the way that it was portrayed in the first place, but also I can enjoy, as an older brother, the fact that my sister... her first Disney princess introduction would be Moana. And I know those are different ends of the spectrum in terms of how critical of things I can be, but I've also heard that thought shared with some of my friends. And then, you know, I think about representation also largely in the types of stories we tell as well, and how the smallness that people say is what renders Pacific Islander communities not worthy of being named or even thought of as existing is deeply rooted in genocide, geopolitics and violence.

Thomas: The archipelago I come from, where I was born in Guam and raised throughout the Northern Mariana, is described as the tip of the American spear. That's what we grew up hearing. And so I reconcile what cartoons and animations can do with what is actually happening in our communities and how visibility can definitely be the start of a conversation, but we can't end there.

Eliza: Tomas, I also cried during Moana. It's a really good movie. It's also the best thing that Lin Manuel Miranda has ever done. Probably the only good thing that he's ever done. I don't think that media representation is the first step. I think it's the last step. I think that media representation is most important for young kids because they're still in the mirroring phase of development. But it's the last step. When you're mirroring, it's when you identify yourself in terms of the other. So from about six months on, kids start to devote a ton of time and effort to exploring the connections between their bodies and the images around them. So media representation can be very positive for them.

Eliza: And thankfully, most kids programming is wholesome, and so is kids literature, but real life representation is even better because Hollywood can't and doesn't care about uplifting anyone's self-esteem. And that's why I always encourage people who scream about more media representation to seek out other Asians in their community who could be positive forces in their families' lives.

Eliza: How often do you see other Asian preschool teachers or elementary school teachers? Hardly ever. But whenever Asian Americans talk about going into education, they always end up going into academia, which is not accessible to most people. I would love to see more Asian Americans in K-12 education — something at the local level.

Eliza: And these are the kinds of people that kids will see in their everyday lives that make the big difference — mom and dad's social circle and the people who are teaching them. Back to the mirroring thing, as parents, you are your entire world for much of your children's impressionable years, so you should make those count. You should use those years to instill in them pride in their heritage and to celebrate their differences instead of ignoring or neutralizing them. Representation just can't begin at the Hollywood or even the media level. It has to start in the household.

Marvin: When people say representation matters, the first thing I think of is yeah, duh. Right? Of course it matters. Of course it matters that you see yourself, your stories represented in not just media, but in life. Right? It's also in our books, in our education, in our governments, in our everyday life. And like I mentioned earlier, representation for me was never an issue because I grew up amongst Asians, Asian Americans, seeing all my friends, my best friends were all Chinese or Vietnamese or Filipino.

Marvin: I grew up between the United States and Taiwan. So I learned English by watching Sesame Street, and I learned Chinese by watching the Chinese version of Sesame Street, right? So representation in media was something that I've always had. And I think that's part of why I grew up more confident in my identity, and it wasn't until I went to college and I met people who didn't have what I had that I realized, “Oh, the way we're going about our identity, like, it's totally different. Right?”

Marvin: Like, meeting people who are self-conscious, who grew up being ashamed of their culture. That was alien to me, and I think that in itself is proof that representation does matter because if you don't grow up thinking that you matter, you're gonna not think you matter.

Eliza: Media representation is a topic that is always so fraught with tension in the Asian American community because it's usually the gateway point for other Asian American issues. Like if you are one of those people, like Marvin has talked about, that probably grew up with not that many Asian people around you, not that many Asian friends, you depended on media representation for your mirroring development. You often don't know the other stuff that's going on, and all the nuances. And representation matters. It's one of the topics that we love to make fun of Unverified Accounts on our podcast. We probably make fun of it at least once every week.

Marvin: And representation is a lot less effective when those characters aren't speaking words from people that represent them, right? We always laud productions when they hire a Asian writer or a Pacific Islander, like when they hire a diverse writer on the writers teams and, you know, studios like to trot that out as, “Oh, this is proof that we have diversity and diversity is winning,” but you know, a lot of people don't understand there’s also a politics within those writers' rooms. And if they're a junior writer and there's a senior writer there that isn't diverse, they have the ability to erase that diverse writer's input. A lot of times that's what causes these dissonances, where we're very excited that we're getting diversity on screen, and then it doesn't live up to our expectations because of one reason or another. A lot of it has to do with the people still making the ultimate decisions are still not us.

Thomas: Yeah. I think a lot about what you just said about representation outside of Hollywood as well, and one thing that comes to mind is stories and coverage of climate change and how disproportionately again, Pacific Islanders are impacted by this issue, but in the storytelling, we don’t hear Pacific Islander or Indigenous voices in those issues. And so that's definitely something I want to echo.

Julia: Eliza, you mentioned that representation is one of the easiest things to make fun of, too.

Eliza: I can count a million ways why it's easy to make fun of it because media representation at the Hollywood level, like it doesn't help you if you're an adult. If you're anywhere over the age of 20 and your hashtag activism is about media representation, how it's going to make such a difference in your life, I really think that you need therapy because Hollywood is not what you need. Your perceptions about Asians and yourself are pretty developed by then, and Hollywood can't and won't fix them. And neither will any young adult novel or Netflix series or Marvel movies. I really think that adults who were fixated on media representation are either job hunting, like they would financially benefit because they're authors or they're actors or someone looking to make a living in that world, or they are probably developmentally stunted and they just want to fix their negative experiences in middle school and high school. I mean, I'm not a psychiatrist, but I stand by what I said. Hollywood is not going to fix or damage your self esteem by the time you're an adult. Earlier this week, to open APAHM, I saw that Lucy Liu, she penned an op-ed in the Washington Post, where she responded to a particularly harsh article in Teen Vogue that talked about the harmfulness of the dragon lady stereotype, and that teen Vogue article singled out Lucy's Kill Bill character — O-Ren Ishii. And she was writing in response to Teen Vogue. The article was called “Hollywood Played a Role in Hypersexualizing Asian Women.” And in it, the dragon lady trope was defined as, “cunning and deceitful” and “someone who uses her sexuality as a powerful tool of manipulation, but is often emotionally and sexually cold and threatens masculinity.” I think that sounds awesome. And like what a fascinating character that I'd love to see more of in movies. When it's not an Asian woman, we call them femme fatales. So I not only imagine someone who's really attractive, but also someone in control. But anyway, Lucy Liu pushed back, rightfully so, and said it doesn't make any sense to single out O-Ren Ishii, when all the other assassins in Kill Bill were portrayed the same way, like sexy, cunning, and stealthy. And like, what's wrong with that in a revenge martial arts movie? What is this demand for morally perfect fictional characters from the media representation, the “representation matters” crowd.

Eliza: So like, if you think that a dragon lady villain or any negative depiction of an Asian character is going to root cause your life to be ruined in some way, I do think that there's something very flawed with your logic. Like I would love to see more shitty Asian American characters in addition to good ones. Sorry. Am I not allowed to curse on your show?

Julia: Oh no, you can curse.

Thomas: Well, that would have changed a lot of how I phrased things. Just kidding. Actually not. But thinking about those stereotypes, and kind of the representation conversation, I mean, just in my own life, I was asked point blank if my people wore clothes back where I came from. But I think I want to say in response to this question that my community is online, but they're also not online. That's not where it really happens. And I think one thing that this pandemic has been really difficult for is that Pacific Islanders live in multi-generational households, gather in so much. Being physically present with one another is so important. And I think a lot about how I want to break out of this hashtag and other than promoting, you know, events that highlight Pacific Islanders during this month, I am also much more interested in in-person exchanges of conversation, ideas, and feelings. That's more powerful, and I hope that with the vaccine, we're able to get to a place where we can gather again to have those conversations, because it's a curse and a blessing to live in an online world, but I know that the work, the conversations and the bonds and the community I want to build is not there. It’s in person with the village.

Thomas: I'm much more interested in a conversation about how we can support Indigenous filmmakers, Indigenous media makers, as opposed to how we can learn to accept what's given to us in streaming services. For me, it's more so how do we get tangible support for our people to express themselves in the way that is true to them?

Marvin: Yeah For me, I definitely resonate with what Eliza said about how Hollywood Representation shouldn’t be the end all be all. And I also help program for the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival, and let me tell you, I am tired of seeing stories about the immigrant struggle. Those stories are important, but there are so many other stories and, you know, there are so many other types of narratives you can tell, like whenever I see an Asian genre film, like a mystery or a scifi, I get really excited, and they don't always turn out to be good, but I am excited that people are getting the opportunity to write different things like cozy mysteries about Filipino kitchens, Asian inspired fantasy. And I think it's easy to make fun of representation because the conversation hasn't moved honestly that much over the last few years, and maybe it'll change now that we have, you know, more people working, and it is partly because of work, right? For a lot of writers the only way to get hired sometimes is to make representation a big deal. Because again, we live under a capitalistic society that assigns value to everything, and if you don't show that your stories have value, they're going to crunch the numbers and say, Oh, it's not worth it to give you money to make these stores or to hire you onto the show. So there's definitely a occupational side to it as well. But like, I was super thrilled that Youn Yuh-Jung won the Oscar for her dirtbag grandma from Minari. Right? Because like, for me, my grandmother was not a dirt bag, but she was a chain smoking, mahjong playing lady up in the neighborhood, right? So that did resonate with me. It reminded me of my grandmother who has passed. Who's passed away for like 20 years by then, but it brought back memories, and it still made me feel a little seen or at least, for better or worse, what's portrayed in Hollywood, portrayed on screen, it’s also other people see us, and I need them to know that not all grandmas are like stoic matriarchs. Some of them like to watch wrestling and drink beers and smoke.

Julia: Yeah, definitely.

Eliza: What's the name of her again? She won Best Supporting Actress. What's her name?

Marvin: Youn Yuh-Jung.

Eliza: Oh, yeah. One of my favorite things that she's done this year, and there are many, is when she was at this screening of the movie and people in the audience or people as part of the panel, like Sandra Oh for example, were like crying. She was basically saying like, “Why is everyone crying? What's the big deal?” That's also how I feel. I'm like, what is the big deal? Why is everyone crying?

Thomas: Yeah. And to add to this conversation, I think when I talk about storytelling, or media, you know, whatever medium it is, I think of it as a lineage that, for me, doesn't require the current institutional validation that I think is typically sought. I recently came across a 1997 transcript of my grandfather, who was one of the first mayors of the Island of Rota and the Northern Marianas. And he was asked by this researcher: “Did you and the other leaders on Rhoda think it was useful to have the United Nations’ Visiting Mission come and listen to you?”

Thomas: My grandfather, Prudencio Mangloña said this. He said, “Well, it's nice to see important people coming to the Island. Very rare to see that. So at least somebody came. No reporter, no newspaper, and no others talked about our problems. So at least those concerned about the welfare of the people.” And so when I talk about storytelling, to me, it's answering a call, whether that's from my grandfather or the ancestors to before him, that we can answer that call in this lifetime. That's what I mean when I say storytelling beyond any institutional validation, Oscar, Emmy, Grammy Tony. It's much deeper than that.

Julia: What do you think is the best way to approach May as Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month? How do we make the most of it?

Thomas: I know what not to do. With or without the month, the work will continue. Our communities will continue to thrive and resist and what it's not, it's not a time to reach out to Pacific Islanders to be part of programs this month. I think one thing that we're also tackling as a group at the Pacific Islander Task Force is that we want to start hosting, and will start hosting, and creating content and panels and engagement that really shows the full breadth of Pacific Islanders in media. Every panel that we have shouldn't necessarily be about their identity. There are Pacific Islanders covering government. There are Pacific Islanders covering cybersecurity. There are Pacific Islanders covering climate change. They should be a part of those conversations at a different level, too. Pacific Islanders shouldn't be brought to the table just to talk about their identity if that's something that they don't want to just do. And so I think I'll leave it at that, that the conversation shouldn’t just be for the month of May.

Marvin: Yeah. I think what I would say is this is a month where the community is hypervisible. So there's going to be a lot of events, a lot of conversations. And I think as someone approaching the month and attending these events, listening to these conversations, to go in with a critical mindset. It's easy to get caught up in the good feels, but at the same time, seek out those conversations from people who are on the ground doing work. People who are questioning the status quo. And, you know, like Eliza said, it's not all about Hollywood. There's so many other ways to validate yourself and to engage with your identity. Try to seek those out as well.

Julia: How about for you, Eliza?

Eliza: I like what we're doing right now. I'll admit, I don't usually talk to people like Marvin or Tomas or to you. I am used to talking to people who agree with me on every single thing and it's nice to be on… it’s nice to have a conversation with people who have completely different backgrounds for me and different perspectives, and I am willing to bet don't agree with me on every single thing. So that's nice and we're all getting along and we're all bringing something new. I also think that if you do have, because there is more visibility this month, if you are someone with a dissenting voice or maybe a more contrarian opinion, this is your chance to put it out there.

Julia: Thank you so much everybody for talking to us and sharing your thoughts. Where can people find you and your work?

Marvin: You can find me @MarvinYueh on Twitter and on Instagram. You can check out the Potluck Podcast Collective, which is the collective of Asian-hosted podcasts that I help manage by going to the website podcastpotluck.com. And you can also check out Books and Boba, which is the Asian American book club podcast that I host and produce by going to the website booksandboba.com.

Eliza: You can find me@aestheticdistance.com. That's my blog. And you can find me on Twitter. You can find me on Instagram. And of course, every Monday, a new episode comes from Unverified Accounts, which you can find anywhere that you listen to podcasts. And don't forget to check out Escape From Plan A podcast, too. I do a lot of work with those guys.

Thomas: Yeah, my social media handle is @thomasreporting, and also want it to plug if you are a Pacific Islander mediamaker, please, if you are on Facebook, feel free to look us up at the AAJA Pacific Islander Task Force and request to join our Facebook group. We really want to hear from you.

Credits

THEME MUSIC begins

Julia: Thanks again to Marvin, Eliza, and Thomas for joining me today! You can find out more about them in our show notes.

Julia: We'd love to hear what you think about these bonus episodes, too. So if you have any feedback, you can email team@selfevidentshow.com to let us know.

Julia: Today's episode was produced by me, Julia Shu, with help from James Boo and Timothy Lou Ly. Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda.

Julia: And make sure to subscribe and check back next week, when James is hosting a conversation about the connections between storytelling and social impact.

Julia: Until then, you can follow us on social media - at self evident show - where all this month our team is sharing events, movies, music, and books that we're excited about.

Julia: Self Evident is a Studio To Be production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts creator program... And our listener community. We also want to give a big thank you to Wanda Ikeda, one of our biggest supporters on Patreon, for helping us keep all the lights on this month.

Julia: Take care, and make sure to also celebrate May by taking all your allergy meds!

THEME MUSIC ends