Episode 012: We Hear You (3/3)

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

How can Asian American communities create safety, when the harms of racism and xenophobia are so deeply rooted in our society?

We’ve spent time unpacking the simplistic solution of hate crime enforcement, then learning how local activists rallying against anti-Asian hate often reveal a much deeper history of neglect and under-resourcing of immigrant communities.

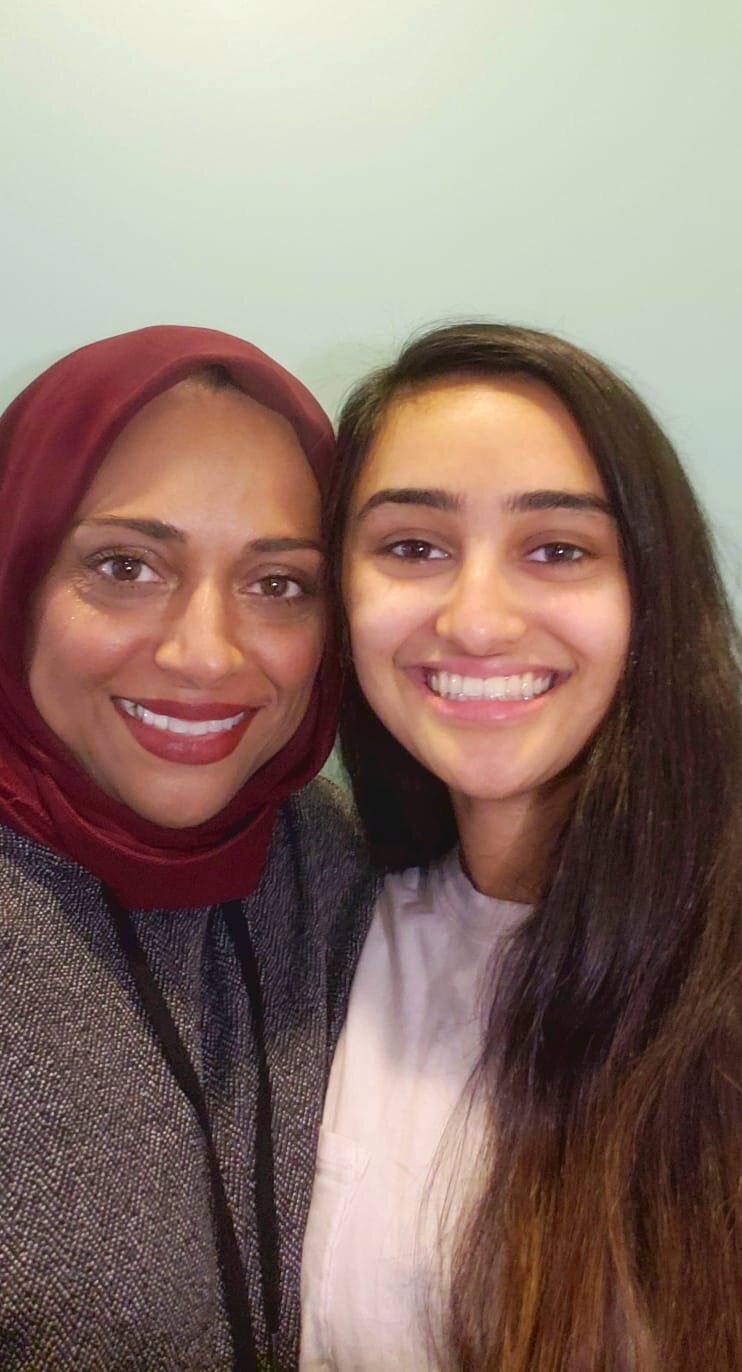

In this third of three episodes on community responses to anti-Asian racism during the pandemic, we speak with four people — Rachel Kuo of the Asian American Feminist Collective; Sammie Ablaza Wills of API Equality in Northern California; and Suja and Iram Amir from American Muslims Uncovered.

From seeking non-policing solutions for conflict management, to helping intergenerational communities understand how to express what they need most, to challenging the racism that festers in schools across the country, each voice in this episode challenges Asian Americans to ask for fundamental change in how we achieve safety for our communities.

Resources and Recommended Reading:

To report a racist micro-aggression, bullying, hate speech, harassment, or violent incident to community advocates, fill out a form at Stop AAPI Hate (multiple translations available)

Sign up for a bystander Intervention Training to Stop Anti-Asian/Xenophobic Harrassment, by Hollaback!

“We Want Cop-Free Communities: Against the Creation of an Asian Hate Crime Task Force by the NYPD” by the Asian American Feminist Collective

“Internal Affairs Investigating Columbus Park Incident” by The Lowdown

“Charges Dropped in New York City Jaywalking Incident” by ABC News

“Trusting Abundance: A Conversation With Sammie Ablaza Wills” by Lia Dun for Autostraddle

“Race, Policing, and the Universal Yearning for Safety” featuring Phillip Atiba Goff for the Ezra Klein Show

“The Store That Called the Cops on George Floyd” by Aymann Ismail for Slate

About:

Self Evident is a Studiotobe production, made with the support of our listener community. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP.

Shout Outs:

Thanks to Rachel Kuo and the entire leadership of the Asian American Feminist Collective, Sammie Ablaza Wills of APIENC, Suja Amir of the Asian & Latino Solidarity Alliance of Central Virginia, and Iram Amir of American Muslims Uncovered for sharing their time with us.

Credits:

Produced by James Boo and Julia Shu

Sound mix by Timothy Lou Ly

Self Evident theme music by Dorian Love

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

Support Our Mission by Becoming a Member!

We’ve launched a membership program for Self Evident, through Patreon.

If you want to help us make this work more sustainable, you can join by donating $5 or more a month. You'll be supporting this mission, and you’ll gain more access to fellow Self Evident listeners, the Self Evident team, and behind-the-scenes moments, as we all come together to keep making the show.

Transcript

ROCHELLE VO: Hi! This is Rochelle, Self Evident’s Community Producer.

ROCHELLE VO: During this season, I’m gathering stories from our listeners, about how they’re confronting racism in their own communities.

ROCHELLE VO: It’s a way for us to amplify voices and experiences from across the country, and stay in touch with what you’re doing to get through this year.

ROCHELLE VO: We’re doing all of this on Instagram. So follow @ self evident show to see these community stories and let us know what resonates.

ROCHELLE VO: And I’m also helping our listeners put on Self Evident listening and discussion parties!

ROCHELLE VO: So if you want to gather around these stories with your friends, family, co-workers or classmates, please let me know by emailing community@selfevidentshow.com.

ROCHELLE VO: Thanks for being in touch. I hope you like today’s episode.

THEME MUSIC starts

CATHY VO: This is Self Evident, where we challenge the narratives about where we're from, where we belong, and where we're going... by telling Asian America's stories.

CATHY VO: I’m Cathy Erway. And this is the last of three episodes in a series we're producing about anti-Asian racism during the pandemic.

CATHY VO: Today I'm sharing three conversations that I had with people from New York, California, and Virginia, who are changing the way we define safety for our communities — as the atmosphere of racism in America shows no signs of subsiding.

CATHY VO: If you haven't heard the previous episodes, called "Hate Goes Viral," and "Here Comes the Neighborhood," please check them out.

CATHY VO: If you have been listening, you'll remember that we left off talking to Patrick Mock and Rochelle Kwan — who are neighbors and friends in Manhattan Chinatown — about a new hate crimes task force run by the NYPD. And whether it will be effective at reducing anti-Asian hate incidents or making people in Chinatown feel safer.

CATHY VO: We also brought up a public letter denouncing the task force, which starts off with this statement:

RACHEL TRACK: "We do not believe this task force will make us safer, but instead put our communities, especially the most vulnerable, at greater risk.”

CATHY VO: That's Rachel Kuo [QUO], one of the co-founders of the Asian American Feminist Collective.

Rachel: Primarily what we do is political education and community building events through different forms of media making, workshops, events things like that...

CATHY VO: Rachel and her co-leaders in the Collective published this letter, in collaboration with over two dozen local community groups.

CATHY VO: After we had heard from Chinatown community members who were asking for more police presence in their neighborhoods, I spoke to Rachel about why the Feminist Collective made this statement — and what public safety could look like, when it doesn't depend on policing as we know it.

Rachel: A lot of the solutions that have been going towards giving more money, more resources towards police, like we haven't seen those result in safety for our communities.

Rachel: And we saw in the wake of 2016, that funding was diverted towards giving different police departments body cameras, and thinking that that would lead to more accountability and transparency, and we haven't seen that.

Rachel: And so I think the kinds of ways that, Oh, we'll give police like more money, more training, more technologies, more resources to better improve policing is just not the solution that we need given both what's happening currently and also these longer history stories of the ways that policing has been really devastating, too, communities of color and immigrant communities in New York City

Cathy: Yeah. Talk about that. Cause he brought that up in your letter too you mentioned that the NYPD has committed violence against Asian American communities in the past, and there's a whole history behind this.

Rachel: There's recent incidents of police violence, that have included viral images of 64 year old musician Wu Yi Zhou being bloodied and handcuffed by police during a performance in Chinatown's Columbus park, or write the story of Kang Wong, who is an 84 year old Chinese speaking man, who was stopped by police when jaywalking in the Upper West side, and he was confused, um, in that interaction and began walking away and then was beaten by police because of that.

Rachel: And so in addition to, to these instances, we know that police are routinely harassing and intimidating, um, Asian communities, such as Asian migrant massage parlor workers and sex workers and using immigration status as a way to intimidate and coerce some of them into nonconsensual sex.

Rachel: This had led to the tragic death of Yang Song in Flushing in 2017.

Cathy: Right.

Rachel: And so I just offer some of these specific cases and there are so many more, but I think with some of these concrete examples, it's not as if police hadn't been in Asian communities prior to the creation of this task force, and it's. It's really clear that both currently and historically that their presence has not improved community safety.

Cathy: So, I mean, at the end of the day, how do you define safety for your own community?

Rachel: Deep knowledge and experience within a community.

Rachel: Thinking about their buildings and their blocks right? Like, do they actually know the people there? Like, what are the relationships that they might have in these local spaces? Because it's really hard to think about safety and accountability when there's a total lack of relationship there.

Rachel: And another way to think about that more, more concretely, right? Is that often in relationships that we have — where harm happens and we're not calling the police — they're often in familiar and intimate friendships like family, friends, other kind of close networks, where there's like a kind of level of accountability that someone has to someone else.

Rachel: What's key here is that there isn't a single blanket solution to safety.

Cathy: So how about when it comes to managing conflicts? Right? So what kind of alternative solutions might be introduced that aren't an armed police officer?

Rachel: Yeah, I think we can think about the ways that different conflicts play out in different settings.

Cathy: Okay...

Rachel: So what it takes to manage a conflict that is happening in somebody's home, like incidents of intimate partner violence versus something that's also happening on the street between two strangers... Those require different solutions.

Cathy: Okay.

Rachel: I think there’s also ways that we can build up responses for disrupting racist attacks and harassment. There are people, like, within communities themselves, willing to intervene.

Rachel: And so I think there’s ways that it's also about building up community support and diverting resources in those directions, which currently, many of those don't exist.

Rachel: We're talking about organizations that are pretty severely underfunded and understaffed.

Cathy: Mmhm.

Rachel: And we're asking, right, like, well, why can't we imagine a kind of solution that is like immediately workable and replicable right now? We need to put the resources there first, and we also need to experiment with what works and what doesn't.

MUSIC starts

Rachel: I think that plays out in a lot of different ways.

Rachel: It can be something as small as going to one's neighbor to kind of find solace and support. It can be like sharing that out with a small network that can offer the kind of care and response to acknowledge that, "Yeah. Like something violent did happen and that harm occurred, and that we believe you," and “We hear you.”

Rachel: That, in and of itself, can be really important to survivors of violence, Which is not happening often at the level of police.

CATHY VO: From our first day of reporting on the rise in anti-Asian hate incidents, we’ve heard frustration over public officials not taking the problem seriously, or making it even worse by associating COVID-19 with China.

CATHY VO: But we’ve also seen a surge in Asian Americans working out solutions for themselves. And when we speak to Asian Americans who are rallying to support their families and neighbors during this pandemic, we often see them drawing on history and solidarity.

Sammie: A lot of the people who were targets of this anti-Asian harassment. Were the same people who lived through the HIV and AIDS epidemic, they are the ones who back when HIV and AIDS first started to make the news were similar. Similarly harassed for quote unquote, "looking gay." Out on the streets, you know, who were told that they themselves are the disease, that they themselves are the virus.

CATHY VO: That's Sammie Ablaza Wills. They're the director of APIENC, a community based organization led by trans, non-binary, and queer Asian and Pacific Islanders.

Sammie: And honestly, the core of our work, what it all boils down to is transformation. We transformed our live conditions. We transform ourselves. We transform our traumas into something that is more restorative so a lot of our work really deals with oral history, fighting for trans justice, building coalition and solidarity with other communities and learning skills for ourselves, for our own people to, get better, to heal, to transform, to be our full selves.

CATHY VO: When the pandemic hit, Sammie had already spent years building relationships and support networks across generations of queer, trans, and non binary folks in the San Francisco Bay Area. They already understood what it was like to be stigmatized and denied the resources a community needs to be resilient and sustainable.

MUSIC ends or fades under Sammie

Sammie: I think in that moment, we turned to that history of especially HIV and AIDS activism and said, during this previous epidemic, how did people stay surviving, despite losing dozens of community members of friends every single week. And what we really found when we looked at the HIV and AIDS epidemic is that this was an opportunity.

Sammie: This was a chance that people turned inward. You know, they didn't just like dig into individualism and say, I'm just going to do all I can to survive, they said, what can we do to survive with one another, and so pretty immediately we started a phone tree to people so that people could stay connected with one another. And it was a low tech way to make sure that people were checking in on one another and talking about their needs and just make, making sure that people maintained a sense of community.

Cathy: I love that idea or that illustration in my head of the phone tree, but could you just sort of try to explain a little bit more about how exactly it works?

Sammie: Yeah, totally. A small group of APIENC community members came together, just started brainstorming a lot of different people in our community, checking in through text, through calls to say, Hey, how are you? What's keeping you grounded right now.

Sammie: And from there, we gathered more interest from folks who said, I want to be a part of a network on a semi regular basis. And so we had people sign up on a form. And from that form, you know, we took people's availability. We took their, um, their interests. So, you know, the things that would keep them excited and grounded in this moment, and we match them up into pairs or into pods of three or four.

Sammie: And we said, here's some things you can talk about. Here's some guidelines, you know, here are some, uh, questions to ask one another to get the ball rolling. Cause this was also. A big relationship building, push, you know, a lot of people on this phone tree in which people were as opposed to just directly call one another had never met before in their whole lives.

Cathy: Got it. And how did that go? What were some of the takeaways?

Sammie: In a pandemic, people are not their best selves. Like they cannot be, and they should not be expected to be their best selves, and I think it was really, really challenging for that group to hold momentum week to week and to hold a sense of shared purpose and shared responsibility, when we were doing something that was so adaptive.

Sammie: They wanted to see us be able to pick up and deliver medicine to people. I wanted to get groceries to people. I wanted to get meals to them. Other people just wanted a purely social space.

Cathy: Was there any, like, really important needs that maybe weren't being mentioned?

Sammie: I think that was one of the most shocking to me, things that came out of the phone tree that even though we were talking to people who I'm very lucky to have known many of these people personally, and we were asking them very explicitly, “What are your needs? You know, what do you need in this moment?”

Sammie: Not a lot of people were willing to be outright about what they needed. You know, it's, it's very vulnerable to ask for what you need and to admit that you need something, even if the function of something is to gather needs.

Sammie: And in that first month of the phone tree, only one person asked us to send groceries. But I knew personally that many more people would need something like this.

Sammie: We then started to offer a three part workshop series, and dug into these things around, "Why is it hard to ask for help? Like, what comes up for you? What did you learn about asking for help? Where does that come from?"

Sammie: And then had people practice, you know, like really vulnerably practice, "What is something in your life you need? Let's practice asking."

Sammie: And it was only after that, that we felt equipped to then offer a really concrete mutual aid project. And it was in that mutual aid project that we said, "All right, you wanna sign up for groceries? You want to sign up for meals. You want to sign up for peer emotional support, we are here and we can do that. We want to offer that to you."

Sammie: And it was then that we started to get dozens of people responding, saying "Yes, actually I do have a need. Thanks so much for asking again. I'm going to let you help me.”

Cathy: Do you think there's some pride and, you know, sort of maybe cultural feelings of shame or privacy mixed up in this?

Sammie: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. I mean, for myself, you know, I grew up in a home in which sometimes, like... we just didn't eat and still then it was not acceptable to ask even other members of the family for help.

Sammie: We couldn't even ask my mom's siblings for things, even though they probably could have provided; I think there's such deep shame and trauma around admitting that you need help, that I grew up around that I internalized and... I think for the rest of my life, we'll have to spend time unlearning that asking for help is actually an okay thing to do.

Cathy: So in America, you know, there's this notion of pulling yourself up by the bootstraps that gets celebrated a lot and kind of used as a way to shame those who have not appeared to, you know, have made it right so far. And I think that, you know, especially in Asian immigrant groups, we do love a good story about how hard our grandparents worked and how they achieved the American dream.

Sammie: These stories are fallacies. They are fairy tales. They are inspiring, you know, sometimes they're really like, I find, you know, I love to watch those really inspirational YouTube videos, where they have the kind of like soft background music, and there's a lot of photos that are like, "And then she like transformed her life,” and it's like a happy photo and I cry.

Sammie: Like those are, they feel good. They feel really good. Oh my God, whenever I need to cry, I'm like, let me just watch a few of those. Like "America's got talent” type things.

Sammie: But those are constructed, those are constructed narratives. And I...

Sammie: I just want to return to… remembering, I want to return to the remembrance of the cultural values that many of our communities held back across the Asia Pacific, you know, learning about this Filipino value that I heard a lot and I saw a lot of pictures about when I was growing up this value called Bayanihan.

Sammie: And I think Bayanihan is often represented by this photo or this, like, drawing of someone who lives in a kind of traditional Filipino house, like a hut.

Sammie: And there is some sort of disaster happening. And everyone in the community comes and they put bamboo sticks under the person's house and they lift up the house together and they carry that entire house. The entire community comes together to carry that house to safety.

Cathy: That's really wonderful. I can see that being like a children's book too,

Sammie: You know, I think there is nowadays actually. Which is beautiful.

Cathy: Oh good, good.

Cathy: You know, one thing that I think is true of the Chinatown neighborhoods we’ve been reporting on, and many similar immigrant communities, is that especially during the pandemic, small businesses are just scraping by.

Cathy: Many of these are family owned shops or restaurants, where say, an act of vandalism or property damage could really feel like the end of their livelihoods.

Cathy: And typically, the police seem like the only realistic means of protection.

Cathy: So on one hand, the police have been a neglectful or negative force that not everybody trusts, but at the same time, there aren’t many alternative forms of protection. Has this kind of tension shown up in your work?

Sammie: Yeah, I think that that conundrum that many, unfortunately, you know, many Asian folks are in that during. The pandemics, you know, if my store gets wrecked or if I don't have, if I lose business, I'm going to have to close down... that is, that is a real, real reality that people are thinking about in this moment. And that should not be the reality to begin with.

Sammie: If someone's life, if someone's livelihood is so unstable that they cannot go three months out of a lifetime of work without profit. Something is wrong with this system, not with them.

Sammie: If a business has been fruitful and hard working for most of the time, it's been around a few months, a year, even a few years, it shouldn't, they shouldn't have to be fearful of their wellbeing of their place to stay of what food they're going to eat; the fact that that's even a choice for people... it's not a choice, you know, think about that. That's actually just explicitly not a choice, that is coercion, uh, that is coercion between two things that should never have to be in opposition, and so…

Sammie: You know, I think I've seen a lot of really beautiful ways that community has come together to support those places, either making amazing mutual aid funds for domestic workers that are out of work right now, who can not go into people's homes funds to make sure that businesses are protected.

Sammie: But I think that honestly, my longer view in society is that it should be okay for people to take a break either because their store's a little broken or because they just need a break. It should be okay for people to take a break or to not work for one second of their lives. Their whole livelihood should not be dependent on being productive 24/7.

MUSIC starts

Sammie: And I'm fighting for a world in which that is the case, but that is going to take a lot of letting go of individualism. It's going to take a lot of letting go of scarcity. You know, the fear that there is not enough, and it is going to take a lot of proactive building of those communities…

Sammie: And those skills, the skills of conflict resolution, the skills of healing, the skills of communicating with one another through hardship...

Sammie: ...we have to be proactive, so that the relationships and the solutions we create are actually viable.

MUSIC ends

AD MUSIC starts

CATHY VO: If you've been listening to Self Evident, then you know how important it is for journalists to truly understand the experiences of the people they write about. That’s why I’m really glad to tell you about a new podcast from some of our favorite storytellers and friends. It's called "A Better Life," a podcast from Feet in 2 Worlds, about American immigrants, and how they're being affected by COVID-19.

CATHY VO: Zahir, the host — and virtually all the reporters — are immigrants, or the children of immigrants, just like our team. And that comes through in their stories, which introduce you to people you may have never encountered any other way. Listen now wherever you get your podcasts.

AD MUSIC ends

CATHY VO: This is Self Evident. I'm Cathy Erway.

CATHY VO: The conversations I had with Rachel and Sammie were about a future where safety isn't defined only in terms of crime and punishment, or law and order.

CATHY VO: And how important it is for us to be proactive — not just in opposing racism, but creating our own ways of keeping people safe. Especially in the places where they're most vulnerable.

MUSIC starts

CATHY VO: In September, Stop A.A.P.I. Hate released a research report, titled, "They Blamed Me Because I Am Asian."

CATHY VO: The report was based on 990 interviews with Asian American youth across the country, and showed that 1 in 4 experience racist bullying. Their research has also identified a pattern of adults, including teachers, doing nothing to intervene.

CATHY VO: So right now, Asian American students are dealing with fear and bullying like never before, along with the nightmare of trying to keep up with school at all during this national crisis.

CATHY VO: We've seen this scenario before — in the form of Islamophobia that has grown and persisted over the past 19 years since 9/11.

CATHY VO: Of course, there are plenty of differences between that event and today’s pandemic.

CATHY VO: But the way our leaders, and especially our President, talk about Covid — stokes fears about national security — even though the virus is fundamentally a public health problem.

CATHY VO: And as we confront racism against students, I thought it would help to hear from a student who’s experienced how this kind of politicized xenophobia spreads to schools.

Iram: The middle school that I came from, even though I had like a negative experience with nine, 11 and fifth grade, the faculty and administration made it a point to, you know, make people feel safe and make them feel comfortable with their beliefs and values. And then I came to a high school where it was the exact opposite of that, where I was made to feel ashamed.

CATHY VO: That's Iram Amir.

Iram: I am currently a junior at Virginia tech and I'm majoring in finance and I am a proud Muslim American with South Asian descent.

CATHY VO: Iram was eight months old when Al Qaeda attacked the World Trade Center. And for her, going to school has included learning just how much the stereotyping of Muslims as terrorists has persisted for a generation of American students.

Iram: And then my sophomore year, I had another separate teacher, which World History II, and that specific time she was talking about Islam and Saudi Arabia and she was talking about just generally Islam and she brought up ISIS.

Iram: And again because I was the only Muslim, visible Muslim in the whole school, pointed me out and basically said that I was a part of ISIS.

Cathy: What did you say to her?

Iram: I didn't say anything. I just sat there stunned. I mean, we had like a class full of like maybe 10 kids in this specific class, so, I was looking around just kind of stunned and everyone was like, Whoa, you're I'm like what? Like, we were all kind of confused because

Iram: I don't know.

Iram: It was just, it's just a lot at once to process.

CATHY VO: Then Iram called her mom, Suja, who happens to be a community advocate in Richmond, Virginia, where she and her family live.

MUSIC ends

Suja: The moment I got off the phone, it was just rage. I definitely had to take a moment and pause.

Suja: At the same time. I knew, especially after she told me, and I'm trying to make this meeting with immediately, like , I am going in there right now. And I'm making this meeting right now. “I'm going to the school right now, l;;ike I'm not even waiting.”

Suja: And, you know, the head of school gives me an excuse, said we'll meet on Monday. To have a strategy, right?

Cathy: Oh, I see. Right.

Suja: And then we had a meeting. The whole time I was thinking, this is a woman who has a PhD, this is a woman who I've had conversations with. And I am in utter shock. she was like, Oh, I wasn't pointing to her. I was just kind of gesturing and, you know, and she started crying, and...

Cathy: Oh my goodness.

Suja: Yeah, it was very, it did not feel at all authentic. and you could see that very clearly. And she said, and then we'll, we're going to be talking about Islam later in the school year. And I said, “Well, I'd like to very much be a part of it.”

Suja: “You know, see what resources you're utilizing and I would be able to provide some resources for you, and maybe we could meet and have these discussions.” Right?

Suja: And, um, you know, we never met, I did give her multiple books, and she never took the opportunity nor did she ever teach that in class that year.

Iram: The thing is, is that I've tried multiple times, not just from my parents, but like I've had my own meetings, and I spoke about it in front of the whole school about my experiences there and I just got... pity "I'm sorry"s. Or "Oh, I didn't know this was happening."

Iram: It's just so unfortunate because I know I'm not the only student there that has had These negative experiences, and there's kids that have gone through worse at that school.

Iram: There's an Instagram account right now going around and students or alum or faculty they'll submit their experiences of what happened at that school, to kind of create awareness of what's going on. And what I thought was interesting was that the principal of the whole school was following that account (laughs).

Iram: So he's reading all of these experiences and he's seeing, you know, there's minorities that are going through Hell and back, and they're not doing anything about it.

Iram: So I would just hope that this account is a good turning point, but I don't know. I really don't know.

CATHY VO: Iram and Suja have also started their own Instagram account, American Muslims Uncovered, where Muslim students — and non-Muslim students, parents, or obsevers — can share their own stories about harassment and stereotyping in schools.

CATHY VO: Suja also hopes to change the inaccurate and anti-Muslim curricula that she's seen taught in Virginia schools.

Suja: Our history continues to repeat this type of marginalization of communities by way of national security and it is, is a framework that continues to promote a very, very, um, dangerous narrative because what ends up happening is these communities become targets, and they're not safe and it continues to create a harm, particularly for children as they're growing up in, you know, society.

Suja: I mean, if I grew up here and I, I felt, you know, some, some issues, but I'm thinking, 2020, my kids have it much more difficult than, than I did.

Cathy: Wow.

Suja: Okay.

Cathy: That's not okay.

Suja: That's not okay.

Cathy: You mentioned history repeating itself. And so one of the things we're exploring in this podcast series is the impact on Asian Americans who are now experiencing racist hate associated with COVID in China. Do you see like parallels to that as a parent?

Suja: Absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, the constant, coded language that they use to portray the virus, the way that it's used in a manner to blame and deflect and not take accountability for the virus.

Suja: And it's not much different the way that they're getting targeted. They're getting targeted in stores. They're getting blamed. They're getting yelled at, they're getting accosted and attacked. It's the same stuff all over again. And I feel for them, but it's because of what we're talking about, that language.

Suja: Remember, words matter. The language that we use to describe these things, change how we respond.

Cathy: It's so difficult when the president doesn't use the right name. I mean, it's so hard to tell teachers and administrations to do something our own president isn't doing.

Suja: That's part that's part and parcel of the problem, right? Well, I couldn't as someone who's a resident of Virginia. My locus of control is here.

Cathy: True.

Suja: If I can help effectuate change locally, then I'll do what I can.

Cathy: Shy of, of a parent who's that engaged and willing to, to take part in these things. what do you think schools, the school should have done? What could they be doing right now.

Suja: I think one of the main things they need to be doing is making sure that the teachers are well versed and trained. the mindset and the structure has to come from the teachers first… and definitely the curriculum.

Suja: And that in and of itself is difficult. And I know that that's something that, especially if you're looking at the public school sector, it's difficult because the teachers already have a whole lot on their plate.

Suja: However, that's not an excuse.

Suja: These stereotypes continually cause toxicity as we continue to promote them. Like continually making this a patriotic issue. We've seen the worst example of that with the Japanese Internment already.We don't want to do that again. We've already experienced that. Let's not go back to that.

Cathy: So in a series of episodes we've been doing, we were talking about community safety and security, so how would you define community safety in your life?

MUSIC starts

Suja: Community safety would look like to me... feeling like no matter what was going on that we would have each other's back, that, you know, just like my neighbor and I call each other from time to time, check in on each other and make sure that we're doing okay.

Suja: As far as for my kids,you know, I've seen safe spaces in some of the schools that they have been in.

Suja: When my daughter was in middle school, they knew she was Muslim. And we didn't say anything other than that she's Muslim, and if she chooses to pray, she might pray. So we're going to give her a prayer rug, and if she wants to go ahead and do it, that's fine, but it's on her.

Suja: And so she came home one day, and she was so excited and she was like, "Mom, you'll never believe this. My teacher, when it was time to pray, she came and told me if I wanted to pray, I could pray in this one space," and that she just made that open for her.

Suja: Which, you know... it's about allowing a child to be who they are.

CATHY VO: This idea, that we should be allowed to be who we are, is so simple. For a lot of us, it’s the first story we’re told about America: It’s where people go so they can be themselves.

CATHY VO: But the truth is more complicated, and less promising, than that story.

CATHY VO: I think what we’re being reminded of, in so many different ways, is that safety goes beyond our individual needs, or the impulse to survive.

CATHY VO: For Suja, community safety means knowing other people have your back — like a teacher making sure you feel welcome at school.

CATHY VO: For Sammie it’s building the relationships and communication to make that community reliance and support possible.

CATHY VO: And for everyone I spoke with today, safety is about taking a hard look at what’s been done in the past. Asking whether it really works. And giving each other some space to imagine the world that people deserve.

CATHY VO: Today’s episode was produced by James Boo and Juila Shu.

CATHY VO: We were mixed by Timothy Lou Ly. Our theme music is by Dorian Love.

CATHY VO: Thanks to Rachel, Sammie, Suja, and Iram for spending time with us. And thanks to our newest members on Patreon! Your support helped us record these conversations, which is pretty tricky to do these days.

CATHY VO: We really want to hear what you think about these first three episodes of our new season! Please email your thoughts to community@selfevidentshow.com.

CATHY VO: Self Evident is a Studiotobe production.

CATHY VO: I’m Cathy Erway. Let’s talk soon. Until then, keep sharing Asian America’s stories.

MUSIC ends