Episode 011: Here Comes the Neighborhood (2/3)

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

The rise in xenophobic harassment, discrimination, and violence against Asian Americans during the pandemic has led to a rise in neighborhood watch groups in historic Chinatowns and other Asian immigrant communities across the country.

While these groups have made headlines for speaking out against racism, their motivations and actions reveal a deeper story about the pain of underserved communities and the role of policing in those communities.

In this second of three episodes on community responses to anti-Asian racism during the pandemic, we report on three neighborhood watch groups in historic Chinatown neighborhoods: the Manhattan Chinatown Blockwatch, the SF Peace Collective, and the United Peace Corps. The diverging approaches that they take reveal how much American communities rely on a “law-and-order” definition of safety.

Resources and Recommended Reading:

To report a racist micro-aggression, bullying, hate speech, harassment, or violent incident to community advocates, fill out a form at Stop AAPI Hate (multiple translations available)

Sign up for a bystander Intervention Training to Stop Anti-Asian/Xenophobic Harrassment, by Hollaback!

Donate to support ongoing food security efforts by 46 Mott in Manhattan Chinatown

“America’s Long History of Scapegoating its Asian citizens“ by Nina Strochlic for National Geographic

“How One Activist Influenced Seattle Chinatown’s Alternative to Traditional Policing” by Claire Wang for NBC Asian America

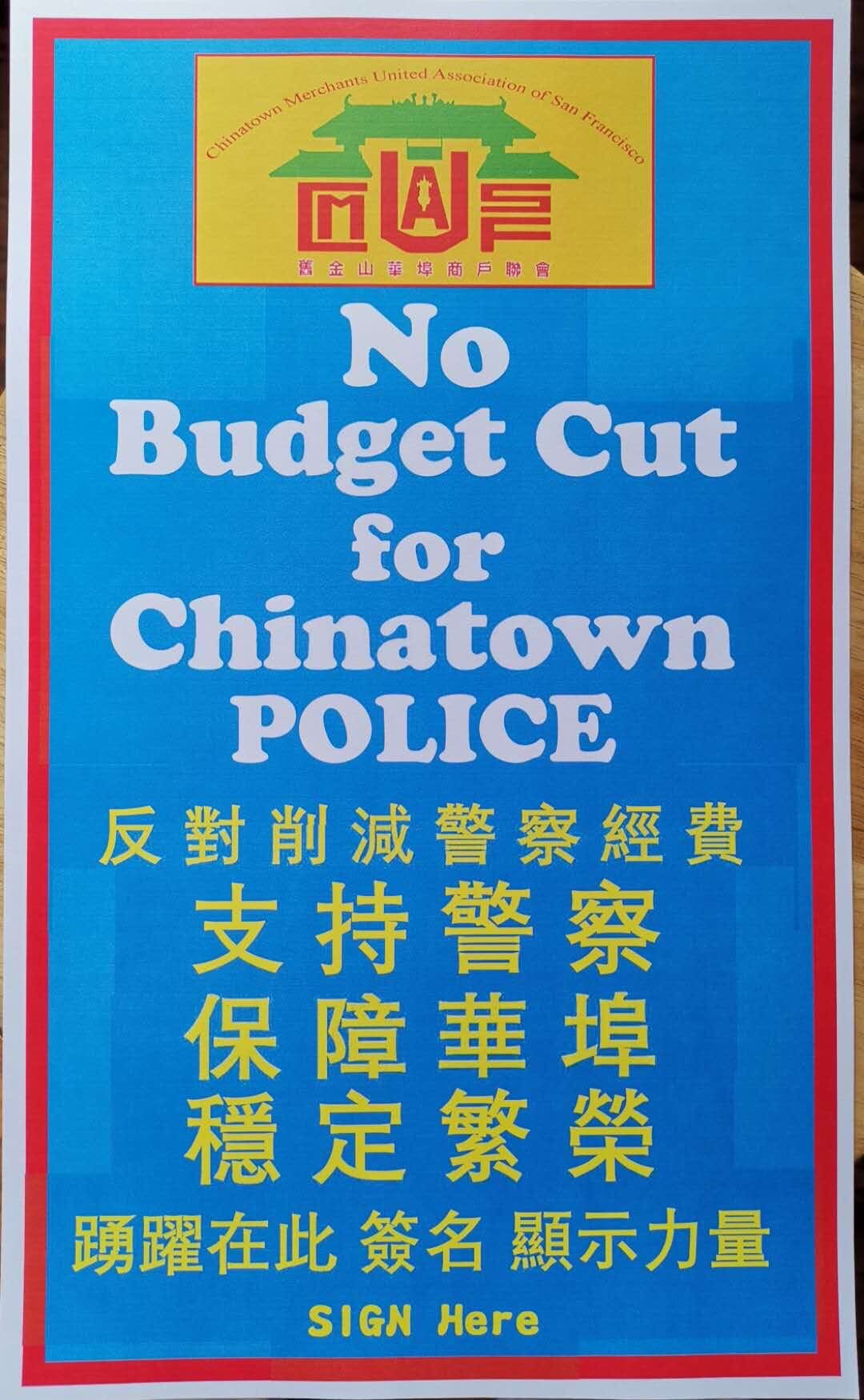

Chinatown Merchants United Association of San Francisco letter to district supervisor Aaron Peskin, requesting more police alongside other services and resources for SF Chinatown

“Critics Fear NYPD Asian Hate Crime Task Force Could Have Unintended Consequences” by Kimmy Yam for NBC Asian America

“We Want Cop-Free Communities: Against the Creation of an Asian Hate Crime Task Force by the NYPD” by the Asian American Feminist Collective and co-signed by over two-dozen community based organizations

“Race, Policing, and the Universal Yearning for Safety” featuring Phillip Atiba Goff for the Ezra Klein Show

About:

Self Evident is a Studiotobe production, made with the support of our listener community. This episode was made with support from the Solutions Journalism Network, and from the National Geographic Society’s Emergency Fund for Journalists. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP.

Shout Outs:

Thanks to Karlin Chan, Max Leung, Leanna Louie, Patrick Mock, and Rochelle Kwan for sharing their stories with us.

Big thanks to Think!Chinatown, Jasper Yang, Alice Liu, and Nancy Law for partnering with us on community reporting for this story.

We’re incredibly grateful to Michelle Faust Raghavan at the Solutions Journalism Network for advising us throughout the reporting process and supporting our community reporting work.

Credits:

Produced by James Boo

Story edit by Julia Shu

Sound mix by Timothy Lou Ly

San Francisco interview and field recordings by Sonia Paul

Production and reporting assistance by Prerna Chaudhury

Self Evident theme music by Dorian Love

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

This episode was produced with support from the Solutions Journalism Network and the National Geographic Society’s Emergency Fund for Journalists.

Support Our Mission by Becoming a Member!

We just launched a membership program for Self Evident, through Patreon.

If you want to help us make this work more sustainable, you can join by donating $5 or more a month. You'll be supporting this mission, and you’ll gain more access to fellow Self Evident listeners, the Self Evident team, and behind-the-scenes moments as we all come together to keep making the show.

Transcript

CATHY: Hey, it’s Cathy. This episode is the second part of a series on anti-Asian racism during the pandemic, and how Asian American communities are responding.

CATHY: So if you haven’t heard the previous episode, called “Hate Goes Viral,” then please go back and check it out.

CATHY: Also, there’s some swearing in today’s stories. Thanks for listening.

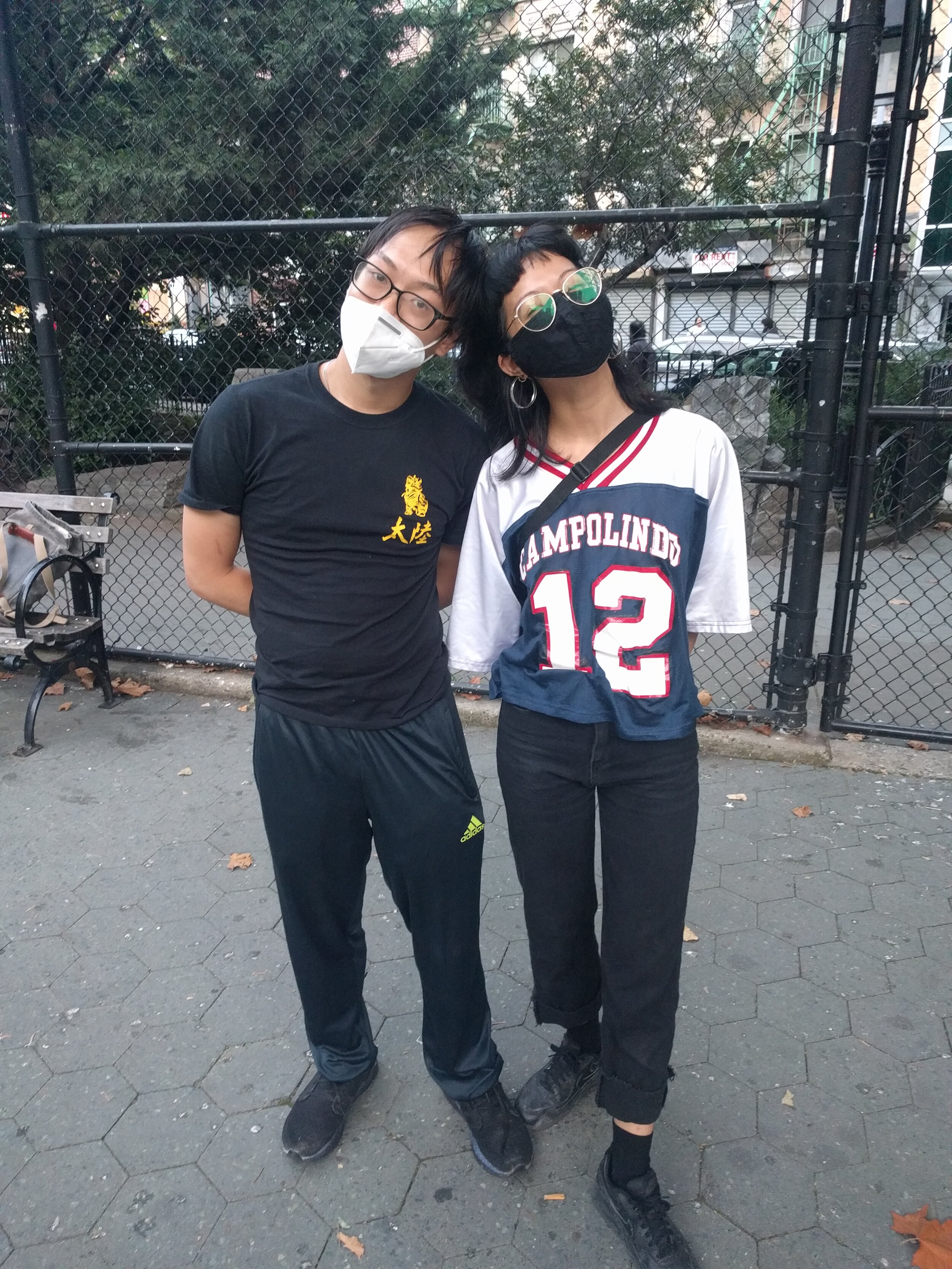

CATHY: A couple weeks ago, our Community Producer Rochelle Kwan, met up with her friend Patrick Mock — who runs a bakery in Manhattan Chinatown.

Rochelle: We brought a table out, we put it on the sidewalk. And laid some newspaper, laid newspaper out on the whole table —

CATHY: — and they gathered a bunch of friends outside the bakery…

MUSIC Begins

CATHY: ...for a crab boil.

AMBI: Patrick and Rochelle’s friends enjoy their outdoor dinner

Patrick: We had like three dozen crabs, corn, potato clams, shrimp all over the table on top of newspapers. And we're just eating with our hands. And instead of a mallet, we were using cleavers. [Patrick and Rochelle laugh]

Rochelle: One of my fondest memories of it is you all coming out with the big pots and just, and just pouring, pouring crab, like endless crabs onto the table and drizzling it with butter.

Rochelle: I learned to crack a crab for the first time, and... yeah, it was just messy.

CATHY: It was around 11pm on a Friday night. Most of the stores were closed, and the only other people out on the street were the staff of a restaurant called New Shanghai Deluxe, just down the block. Also having dinner together on the sidewalk.

Rochelle: And they're always having their family dinners. So, it was just us and them.

Patrick: So we were at crab boil, chilling, enjoying ourselves.

Rochelle: And then we started hearing a commotion at the restaurant down the street.

MUSIC takes a dark turn

Rochelle: I remember hearing a big thud, and then I looked over, and then there were chairs kind of flipping over, and aunties and uncles were wrestling with somebody. And I couldn't really tell who it was they were wrestling with, it just kind of looked like a big mob of people...

Patrick: ...and then we saw, like, everyone that was eating at the restaurant just jumped on this person.

Patrick: We saw like a broken window and a rock on the floor, and so we kind of put the pieces together —

CATHY: So here’s what happened. A man — who was Black, in his late 20s, and lived in an adjacent neighborhood, walked to Chinatown and threw a rock through a bakery window. Then he came down the street to this restaurant, where the staff were sitting outside, having dinner after work.

CATHY: He threw a rock at their window, then started verbally harassing them.

CATHY: The restaurant workers got up and pushed this guy to the ground. That’s when Rochelle and Patrick and their friends came onto the block.

Rochelle: He was on the ground against the wall of the building, and I remember seeing one of the people grab the trashcan and, and want to flip it over on top of him.

Patrick: It was pretty much all these angry Chinese people just beating up on the dude.

Rochelle: It was very clear he was.. he was going to get overtaken.

CATHY: Patrick’s 26 years old, and he’s lived in Chinatown for every one of those years. So everybody around here knows him and trusts him.

CATHY: But when he tried to break up the fight — the restaurant staff were furious.

Patrick: “Oh you can't let him do that to the Chinese, just can’t let them, like, you know take advantage of us.”

Rochelle: One of the aunties was holding the rocks, and I got really scared I was scared that there was somebody on the ground and that these rocks were meant to be used to hurt this person.

Rochelle: And (nervous chuckle), I think there was a moment of also…

Rochelle: ...“I can't believe I have to disrespect my elders right now and step in and tell them to stop doing something like this.”

MUSIC fades out

Patrick: “Like, cause it was getting out of hand like you already beat on this guy. We're not trying to kill him right now.”

Cathy: Wow. Do you... do you think that these folks wanted to and were going to kill him, really?

Patrick: I mean they were emotional and heated in the moment when you're emotionally heated In a moment you just let your emotions run wild.

Rochelle: Yeah. I can't say if they were trying to kill him, but I agree with Patrick that we don't know where that could have led.

Patrick: You got to de-escalate this situation.

BEAT

Rochelle: Somebody from our group called 911. and then within a few minutes the police arrived.

Rochelle: And I’ve been thinking about this situation a lot.

Rochelle: I... feel very strongly about defunding the police. But in that situation, we were the young people who were calling the police.

Rochelle: It felt like they were the only people that these older folks were going to to respect at that moment.

Cathy: Why did you think that the older folks didn't call the police?

Patrick: Because if you know the history of Chinatown, we're kind of always about self policing and, and they're from that generation, about... how gangs ran Chinatown, and cops were just there on the side lines.

Rochelle: One of the older men was saying that even if this person gets arrested, they're just going to let them out again, and then he'll be back on the street, so they had to teach him a lesson, so he didn't want to come back.

THEME MUSIC starts (light)

CATHY: This is Self Evident. I’m your host, Cathy Erway.

CATHY: And I’m sharing this story about Patrick and Rochelle in Chinatown, because this one incident bundles up a lot of questions we’ve been asking ourselves as we’ve watched anti-Asian hate incidents rise across the country — and followed how people in historic Chinatowns are responding.

THEME MUSIC starts (full)

CATHY: When people in these communities feel targeted, who do they reach for to feel safe?

Leanna: Then he started walking away. I started following him. And then at that point I called 911.

CATHY: How do these actions fit in with efforts to change how policing works in America?

Max: I don't want to call the police on somebody who's African American. You know, I'm not trying to get anybody killed or murdered or wrongfully incarcerated.

CATHY: And what would it take for people in underserved neighborhoods to feel ready for a new approach to safety?

CATHY: We explored these questions by reporting on three neighborhood watch groups in New York and San Francisco. These are volunteer organizations that popped up in response to anti-Asian racism, earlier this year.

THEME music ends

SOUND: Mix of street noise and chatter from people in a queue

CATHY: One of them meets three times a week, just outside Patrick Mock’s bakery in Manhattan Chinatown.

SOUND: A door opens and wind chimes ring out, knocking against it.

CATHY: We made this recording back in May, a few weeks after the peak of confirmed COVID infections in New York City.

CATHY: At the time, Patrick was running a food drive, where he accepted donations, then used that money to make two hundred hot lunches, every day, for anyone who needed them.

SOUND: Tea pours into cups, and Karlin describe the line

CATHY: Karlin Chan, a longtime Chinatown local, started showing up every day to help — wearing a face mask and using disposable gloves to pour cups of hot tea for people to take away with their steamed buns, rice, and vegetables.

SOUND: Karlin keeps pouring tea as he talks.

Karlin: Sunday, it’ll be a month.

Patrick: That's how you know we enjoy it.

Karlin: I tell you, Hurricane Sandy, right? I got into that FEMA thing. I'm knocking on doors all over the city, Coney Island, brick and, uh, uptown on the East side, and there, you know. and before you know it, it was like a year and a half had already gone by.

CATHY: So yeah. This wasn’t Karlin’s first time rolling up his sleeves during a crisis.

CATHY: He has silvery grey hair and a long goatee. He was carrying a cane that was more for swagger than for walking.

CATHY: And even in his ‘60s, technically retired, Karlin definitely has swagger. Kind of a tough guy charisma that’s actually pretty disarming.

Michelle: (Distant) It’s really good though what you’re doing… (ducks under Cathy)

CATHY: That’s Michelle, one of Karlin’s friends. When she told him, “It’s really good what you’re doing. You’re helping the elders,” here’s what he said:

Karlin: I'm a fucking elder! Fuckin... cut that shit.

Karli: I'm going to throw one of these at ya!

MUSIC begins

CATHY: When the food ran out, more of Karlin’s friends showed up, for the Chinatown Blockwatch. It’s a neighborhood watch group that started in response to anti-Asian hate crimes and harassment.

Rozina: I live in Chinatown. And in the first couple of weeks when I come out, this was quite scary.

Grayson: People in my family, that live in Chinatown or New York or New Jersey even. They've also been getting the same news as I have and when you see those things, you just don't feel comfortable walking around, knowing that there's this sentiment against you.

Michael: So I decided, you know what? I see a lot of crimes happening. A lot of elders getting beaten up, getting picked on, and get harassed because they're Asian, you know, and...

Rozina: ...and I think the presence of a community, people who care, just the presence would kind of make people feel safe.

Michelle: New York City is the best. We have so much diversity, that racism should not even be here in this state. It should not be tolerated either.

CATHY: Even though over a thousand anti-Asian hate incidents had been reported at the time, it was likely that many more incidents would never be reported.

CATHY: That wasn’t news to Karlin. Back in 2016, after two violent knife attacks against Asian New Yorkers, he worked with the NYPD to host a town hall about hate crimes against Asian Americans.

CATHY: But it’s not just hate incidents that are under counted. We heard from Blockwatch volunteers that a lot of petty crime and acts of violence in Chinatown have gone unreported.

MUSIC fades under Karlin

Karlin: It's frustrating when you dial into nine one one or you go through the precinct.

Karlin: If they don't have a Chinese language, uh, uh, officer on duty, uh, it becomes, it becomes a task. But you, you're going to spend two or three hours there, trying to describe whatever —

CATHY: Then, on top of these issues with access, if someone in Chinatown did get police attention, what the police could do is find the person who, say, mugged them, or followed them into their building... and try to charge that person with an offense.

CATHY: The victims who need help don’t necessarily trust that process.

Karlin: "All right, they took $40 all right. I didn't get hurt. They know where I live.”

Karlin: They don't want retaliation. So, you know, they're discouraged that way from reporting an incident.

Karlin: That's why we have this block patrol, y'now what I mean? We're highly visible deterrent. We will record, we will document, document. We will be a witness to it and we will, we'll help the victims report any incidents or harassment or attacks.

CATHY: Karlin’s Blockwatch criss-crossed the streets of Manhattan Chinatown in the middle of the afternoon, saying hi to neighbors and checking up on business owners.

CATHY: This group came together because people in Chinatown were on edge about anti-Asian racism.

CATHY: But the biggest problems were still rent, food, and the virus. A lot of Chinatown’s livelihood depends on small, family-owned businesses on the brink of survival.

SOUND: Karlin speaks to a shop owner in Cantonese, handing him a flyer and instructing him on where to display it

CATHY: Karlin handed out bilingual flyers that businesses could post in windows, stating that customers have to wear a face mask to go inside.

Karlin: So as the need comes in, if another community group wants to get information out there about a government grant for small business or any kind of government aid for residents, even private citizens. You know, we'd like to get that information out there.

CATHY: A lot of what the Blockwatch does is actually stuff like this. Sharing information. Asking if people are OK. Pitching in where they can.

MUSIC begins

CATHY: And like any group of friends, they were taking selfies. Making each other laugh. Trying to bring back some of the energy that used to fill the Chinatown streets every day.

Steve: It is MASTER CHAN.

Michelle: Oh shit (laughs)

Steve: It is MASTER KARLIN CHAN.

Karlin: Look at my tattoo. Got my Tattoo.

Steve: (laughs) Okay!

Karlin: WE TIGER! DRAGON! CROUCHING TIGER! HIDDEN DRAGON! OOOOOOOOHHHHHH!

Michelle: (laughing) You so crazy!

CATHY: Meanwhile, across the country, Max Leung [Max lee-YOUNG], founder of the San Francisco Peace Collective, was on his own neighborhood watch.

Store owner: Hey Max! How are you?

Max: Good. How are you?

Store owner: Good! Yeah, have a good day, Max!

Max: OK, you too, be safe!

SOUND: Idle chatter (ducks under Cathy)

CATHY: Max, who’s in his late 40s, was wearing his long black hair tied back, using a bandana as a face mask.

CATHY: He had actually wanted to do this neighborhood watch thing for years.

CATHY: Nobody ever took him up on the idea. But once the pandemic hit, dozens of people showed up to volunteer.

MUSIC ends

CATHY: San Francisco is actually the oldest Chinatown in North America. So every time the Peace Collective goes on patrol, it’s like a tour of all the little things that make it special to the people who share part of that history.

Max: My uncle owned a bakery. In that alleyway.

CATHY: Especially Max.

Max: Every time I walk through Chinatown, it always brings me back to, like, my childhood.

Max: I moved away when I, when I was young and it's like only recently because of this, that I really came back and started, you know, plugging myself back into the community.

Max: It feels good.

SOUND: Max keeps walking the patrol (ducks under Cathy)

CATHY: He popped into a popular bakery, which he unofficially called “The Pork Chop House,” to see how the owners were doing.

Max: Saying hi.

Restaurant owner: Oh, thank you!

Max: How you guys doing? Everything Okay?

Restaurant owner: Nothing's happened. Which is good news.

Max: Okay. Yeah, exactly. Okay. Take care, be safe!

CATHY: Max was checking up because of a prior incident.

CATHY: About a month before, he was standing a few doors down the street, in front of another restaurant.

Max: ...and out comes running, this guy, and the ladies who were working inside the restaurant were screaming. So I went inside the restaurant to see what was going on.

MUSIC begins

CATHY: The restaurant workers said the guy had tried to grab some cash from the register, so they had shooed him out the door. Then he went down the street, to the Pork Chop House.

Max: He asked for some food, they gave, they gave him a bun and he tried to steal and take some other things and was just causing a ruckus inside. They kicked him out and they locked the door.

CATHY: That’s when Max first spotted the guy. He looked agitated, so Max approached him casually and asked —

Max: “Hey, how you doing? Do you need anything? You know, like, what's going on? “

CATHY: As the bakery workers watched from inside, Max tried to lower the tension through conversation.

Max: and that's when he, he just focused on, on the button that was wearing.

Max: And the button said, "Save Frisco."

Max: And, and he said, “I like your button. I want your button.”

Max: And I said, here, here, man, you can have it. Just leave, you know, these innocent people alone, you know, let's just be safe out here and try not to cause any problems.

Max: So I gave it to him, he said, thank you. I gave him a pound.

Max: And he was on his way.

MUSIC breaks down to drums

CATHY: One thing Max didn’t do… was call the cops.

Max: that's not my job. You know, like my job is to... to be a visual deterrent. To, to assist and help out in any way I can, but I don't feel like my job is to call the police. And I really don't want to involve, involve the police if I don't have to, for, for a number of reasons.

Max: One being that he was, um, African American. Like, I, I don't, I don't want to call the police on somebody who's African American given the history of what might possibly happen in the worst case scenario and what the outcome might be. You know, I'm not trying to get anybody killed or murdered or, you know, or wrongfully incarcerated, or to have to go through the broken judicial system.

MUSIC continues

CATHY: When we asked Max about his experiences with police, he told us how he got pulled over twice, right after buying his first car — and one of the officers called him a, quote, “stupid chink.”

CATHY: Then he told us that he once tried to make an ATM deposit, and was swarmed by police with their guns out, because someone inside had reported him as suspicious.

Max: And I actually know people who, whom I grew up with, who are, who are now police officers, and in my opinion... like these people should not be police officers.

MUSIC ends

Max: We are trying to be an example of what peaceful conflict resolution can look like.

Max: When we observe and analyze and assess the situation, our first thought is how to deescalate the situation, and not create any harm.

CATHY: Whenever someone joins the SF Peace Collective, they have to sign a contract, committing to eleven principles, which Max says are based on the ancient wisdom of the I Ching.

CATHY: The principles have names like “Youthful Folly,” “Nourished Waiting,” and “Receptiveness.” They encourage volunteers to listen before speaking, to be patient and respectful when facing a conflict, to put the collective good above their own ego.

CATHY: These principles are kind of abstract, so it’s not exactly clear how they’re put into practice.

CATHY: What is clear is that Max saw a chance for regular people from the neighborhood to make Chinatown feel safer.

Max: I mean, anybody can do what we're doing.

Max: For those who feel like they can do a better job, you know, please, please do. I want you to, you know, we need you to, you know, anybody who thinks that they can do better, you know, they, they should.

Max: You know, rather than, waiting for the police to help, or waiting for the politicians. You know, like why not just step up and take it upon ourselves and to do what we can to make a difference?

CATHY: Max threw himself into his mission completely, bringing as many people as possible into his vision for peace.

CATHY: But not everyone wanted to step up in the same way.

CATHY: After the break: Another neighborhood watch group in San Francisco Chinatown decides that peace actually means more police.

CATHY: And we’ll find out what Chinatown community members think about all of this.

BREAK MUSIC ends

JAMES: Hey, it’s James. I produced the stories you’re listening to right now.

JAMES: Self Evident is an independent show, which, to be honest, means we do a lot of unpaid work to bring these stories to you. There’s research, reporting, recording, script writing, editing, community outreach, fundraising, all kinds of administrative stuff...

JAMES: It’s a lot. So if you want to help make our work long-term and sustainable, then please, join our Patreon. You can donate $5 or more a month, and you’ll get access to special behind the scenes content, a private Facebook group, virtual karaoke that doesn’t involve being on Zoom… really, you tell us. Because we’re excited to get feedback from listeners that could make this membership program more valuable.

JAMES: Sign up using the link in our show notes, or just press pause and go straight to patreon.com/selfevidentshow. And if you want to help out with a one-time donation, then you can do that at selfevidentshow.com.

JAMES: Thanks for listening.

BREAK MUSIC ends

CATHY: The sun was setting on a summer day in San Francisco Chinatown, and the SF Peace Collective was wrapping up their foot patrol, when they came across a woman handing out business cards.

CATHY: Her name was Leanna Louie. She stopped to say hi to each of them by name.

CATHY: And Leanna knew their names because she was actually one of the earliest members of the SF Peace Collective.

SF Peace Collective volunteer: How long you guys been out?

Leanna: Oh, since 10:30 this morning. Good guy. All day, we painted, starting from the, uh, 800 block of Stockton.

CATHY: She had over a hundred photos of graffiti in Chinatown, and was determined to paint over all of it. Then, she rolled up her t-shirt to show another t-shirt underneath.

CATHY: It was royal blue, with white letters that spelled out the words: “United Peace Corps.”

Leanna: We're a volunteer group. Just like these guys are out here to patrol Chinatown and keep Chinatown safe.

MUSIC begins

CATHY: Leanna grew up in San Francisco and spent a lot of her childhood days in Chinatown, like Max.

CATHY: She and her partner Robert were two of the first volunteers, along with Max, to start patrolling the neighborhood in March.

CATHY: But a couple weeks later, they left the SF Peace Collective over disagreements about how to do the work. That’s when they started the United Peace Corps.

CATHY: Earlier, I showed you how Max handled an unexpected conflict. So maybe the simplest way to know the difference between the SF Peace Collective and the United Peace Corps is to hear this story from Leanna — which started outside her family association building in Chinatown:

Leanna: I looked out the window and I saw a guy doing graffiti. He was scribbling his name on the wall on Clay Street, on 810 Clay Street. And I was like, Oh my God, I got out of the car and I started recording him and I said, excuse me, what do you think you're doing?

Leanna: And, he goes, “What the fuck are you filming?” I said, “I know what you just did.”

Leanna: Then he started walking away. I started following him. And then at that point I called 911 and I said, “Hey officer, we just did two days of graffiti removal, and this guy just did graffiti right in front of my face. I got him, I got him on video, and I have his picture.”

Leanna: And I asked him to come and, you know, come talk to the guy. You know, I don't know what they do with graffiti artists. (chuckles) Hey, I'm not a law enforcement officer, but I do know when a crime is committed.

CATHY: Leanna said that by the time two police officers arrived, she had been following this person for almost ten minutes.

Leanna: They searched them and they found two graffiti markers, and the colors matched. What was written on the wall. Then they asked me if I wanted to press charges. I said, “Yes, I do, you know, that's my family association that he's defacing. And I want him to be charged.”

MUSIC ends

CATHY: Leanna’s served in the Army and in the Fire Department. She doesn’t think policing is a broken system. She thinks it’s understaffed, and unrepresentative of the people being policed, especially when it comes to Chinatown.

Leanna: When we first started volunteering, we talked to the, um, the Sergeant at the central station and he said, you know what? We actually allocate, um, officers to patrol here, but, you know, we're not seeing the numbers.

CATHY: Leanna decided to make those numbers go up.

CATHY: And this is an important detail. When people talk about crime rates, they’re really talking about reports filed by police.

CATHY: If victims don’t report a crime, or if police don’t pursue an offense, then legally speaking, it’s like that crime never happened.

CATHY: So for Leanna, success means making the police reports reflect what she sees in Chinatown.

Leanna: We've been patrolling since March 22nd from March 22nd to today, which is July 28th. just our group alone. We have filed 46 cases, and of the 46 cases, 28 of them involve police contact. And, uh, eight of them ended up in arrest.

CATHY: According to Leanna, those incidents include public disturbances, need for a translator to assist with a medical emergency, locating a missing family member, repeated assaults on a security guard, and a couple of car break-ins.

CATHY: The United Peace Corps has over 30 volunteers, collaborating with locals to run surveillance on Chinatown 7 days a week.

CATHY: Practically speaking, that means walking around the neighborhood while using group texts to keep in touch, and using phones to record what they think is suspicious activity.

Leanna: And then, you know, if it turns out to be nothing, then we just delete it. And if it, if the situation is you're going to escalate, or if the person who's causing problems becomes violent, then we call 911, and then we have it on recording. So, you know, we always try to have proof.

Leanna: And that's one thing that we've been trying to encourage everybody to do is that, “Hey, before you report a crime, make sure that it actually was a crime. Make sure you take pictures of it and have video recording of it, so that when the police does come, you know, and, and somebody does get arrested, you have proof.”

CATHY: In every story Leanna told us about a time she called the police, there was a moment where she made a judgment call about the person she was watching.

MUSIC starts

CATHY: One time she saw two white men walk down the street, looking into the windows of closed businesses. Then one of them stopped and looked into a car.

Leanna: And he was looking at it for like a minute, like more than a minute! So I was like, “Oh, my God, it looks like they want to break into the car.”

Leanna: So I walked up to the, to the guy and I said, “Hey, excuse me, why are you looking inside my car?”

Leanna: And, uh, he says, he says, “What, can’t I look? Is it, is that a crime?” I said, “No, it's not a crime, but you’re looking in my car for a long time. I don't appreciate it.”

CATHY: Another time, a Black man was reportedly behaving erratically inside a local shop, leading customers to leave. The shop owners were upset. Leanna asked him to leave the store.

Leanna: I started recording him and, uh, and I sent a video to the police officers that we normally contact. And, uh, we also asked the store owner to contact 911 because he is, he might be a threat. You know, he, he took off his shirt and he looks like he's about to fight.

CATHY: So much of the national conversation around justice right now is about who decides when someone is a threat, or a suspect. And how we send law enforcement to look for these threats in the first place.

CATHY: Because in America, we tend to associate Black and brown people with crime, and we’re used to seeing that association lead to over-policing, and unjust killings.

CATHY: We’ve seen video after video of police officers ending the life of someone they consider to be a threat, when that person wasn’t really a threat to anybody.

CATHY: And two of the most widely shared videos in 2020 were not even of police. They were of regular people.

CATHY: A white woman, Amy Cooper, called 911 to tell them that a perfectly peaceful Black birdwatcher was threatening her. A white father and son followed a Black jogger, Ahmaud Arbery they assumed was a criminal, and shot him to death.

CATHY: So, even though this is a different set of circumstances, I still find myself asking: Could the United Peace Corps also fall into this pattern?

MUSIC arrangement shifts

CATHY: Leanna’s volunteers don’t carry guns or knives or batons. They have a policy of avoiding any physical contact with anyone they approach. They don’t go into businesses unless given permission by the business owners.

CATHY: And Leanna says none of their actions have led to violence — from their members, from the people they report, or from the arresting officers.

MUSIC ends

CATHY: When she told us about following two men because she thought they were going to break into a car, we brought up a potential criticism of this approach: That it could actually escalate non-violent situations into violent ones.

CATHY: Here’s her response:

Leanna: We're, we're not there to cause fights. We're not there to provoke anybody into fights. We’re there to find out what's going on.

Leanna: I'm not going up to them and saying, "Hey, I'm going to kick your ass !"Or something like that. I'm not going, "Hey, stay away from my car. I'll kick your ass.!"You know, I, I don't talk to them like that, you know? I talked to them in the cordial way, just like I would talk to anybody.

CATHY: Leanna said that every time she’s confronted someone like this, they’ve stopped whatever they were doing and walked away.

CATHY: Then, we pointed out that neighborhood watch groups and law enforcement do engage in racial profiling against minorities, and asked what she thinks about those concerns.

Leanna: I think that that's always concerning when somebody points out, “It’s just one race of people doing this,” this or that, and I actually have to correct some people who, call people certain names and, you know, derogatory racial slurs against other groups.

Leanna: Like I have to tell them, Hey, you cannot say a certain word about certain people because if you do, you're already mentally thinking that they're bad people.

CATHY: I think it’s important to acknowledge that some people fighting anti-Asian racism do make anti-Black comments.

CATHY: When reporting, we heard remarks from Chinatown residents that essentially equate Black people with crime, and we also heard claims that Black and Latinx people are more frequently racist towards Asians.

CATHY: So we asked Leanna if volunteers for the United Peace Corps are given any kind of anti-bias training.

CATHY: She told us that they’re trained by a longtime museum security guard who focuses on how to spot suspicious activity. This includes a statement against racial profiling.

Leanna: See, I don't believe in that.

Leanna: I believe that there's criminals in all colors and all races. And actually, we have caught thieves that were, uh, there was a Chinese lady, there was a Vietnamese guy. There was, uh, two white guys. Uh, there's a Hawaiian guy. There's two black guys...

Leanna: I mean, you know, I can go on and on and on, you know, how many people we have I caught. But, it's very important that we don't, put a race to, uh, the criminal, a criminal is a criminal regardless of their race, you know?

MUSIC starts

CATHY: This all started when Leanna, Max, and Karlin heard about hate incidents against Asian Americans, and decided they should do something about it.

CATHY: But out of all three groups we spent time with, Leanna’s the only person who’s stopped a hate incident in progress. And she was actually the target.

CATHY: On Friday, August 7, she was painting over graffiti.

CATHY: A white man approached her out of the blue, called her a “Chinese virus,” and told her, “Go back to China where all the fucking diseases come from.”

CATHY: She called 911. A few officers showed up. They arrested him on the spot, because he was already being pursued on a warrant.

CATHY: Her Facebook post says, “All’s well that ends well,” and lists the phone number for the United Peace Corps.

CATHY: The end of the posts asks for volunteers, quote, “to help keep Chinatown safe.”

MUSIC ends

CATHY: Our producer, James Boo, reported these stories.

CATHY: And James, you and Rochelle actually did a survey of people in Chinatown, about public safety, right?

JAMES: Hey! Yeah, so our team did an independent survey of people who live and work in these Chinatown neighborhoods, in Manhattan and San Francisco.

JAMES: We asked a dozen questions to find out whether they feel more or less safe now than they did a year ago; whether they feel targeted for harassment and violence because they’re Asian; and what they would ask for to feel more safe.

CATHY: OK, but let me ask something basic: Did your survey show whether these neighborhood watch groups are working?

JAMES: Well, first lemme say that the survey results aren’t statistically significant. We got around a dozen responses in each neighborhood, and they mostly represent local small businesses.

JAMES: Now, there’s no evidence to suggest that these neighborhood watch groups lower the rates of hate incidents. That kind of effect is extremely hard to prove.

JAMES: But our survey and our reporting did show that business owners and workers, in particular, people with high levels of public contact, do feel safer with these groups on patrol.

JAMES: Especially in San Francisco Chinatown, where 63% of people surveyed had directly experienced violence, robbery, harassment, or vandalism in the neighborhood, and just over half of respondents feel they’re targeted for crime or harassment because they’re Asian.

CATHY: I actually think the benefit of feeling safer is kind of obvious, and it really is valuable.

CATHY: We could analyze these groups as a response to anti-Asian racism, but ultimately they’re more about showing up for a community that’s just... been through a lot.

CATHY: I think it’s part of a wave of local responses that we’ve seen come out of the pandemic, supporting marginalized communities across the country.

JAMES: But at the same time, there are major disagreements about how to best protect people in Chinatown communities.

JAMES: When we asked, “What is one thing you’d request to improve public safety in the neighborhood?” a little over half of respondents asked for more police.

JAMES: In San Francisco Chinatown, over 3,000 people signed a letter to Mayor Breed, asking that any budget cuts to SFPD exclude Chinatown, where local business owners in particular feel like they’ve spent a lot of time and effort building a better relationship with the local precinct.

JAMES: On the other hand, here in New York, over two dozen Asian American community groups, including groups based in Chinatown neighborhoods, have denounced a new police task force dedicated to anti-Asian hate crime, because of how NYPD has profiled Muslims, ticketed Asian immigrant workers, and cooperated with ICE to deport undocumented people.

JAMES: And to be clear: Those are the issues with police contact that come up just within Asian immigrant communities.

JAMES: We haven’t even gotten to the conversations where Asian Americans are calling for police accountability and police abolition, in support of Black Americans and the threats they face from police on a daily basis.

CATHY: Right, and I’m looking forward to having some of those conversations more fully in our next episodes.

CATHY: But I do want to get back to this task force, and the fact that every time we hear about anti-Asian hate, the conversation seems to go straight to hate crime laws.

CATHY: Because I think we’re learning the limits of those laws. Even if we prosecute a bunch of hate crimes, the majority of anti-Asian hate incidents aren’t even counted as crimes.

JAMES: Exactly. And like you said, the social functions of these neighborhood watch groups, they’re not only about crime.

JAMES: So stepping back, I think it’s worth asking: Is a decrease in the crime rate always the same thing as an increase in safety?

JAMES: Cause earlier in the episode, during Leanna’s story, I think you made an important point, that the idea of an objective “crime rate” is flawed.

JAMES: Like, we did our own local survey, and it was really difficult to get responses. Hate incidents continue to be underreported.

JAMES: So that leaves us with the police crime stats, which people in Chinatown have never fully believed.

CATHY: I see, so we’re back to the original problem, that the official number of crimes is inaccurate.

JAMES: I would go further and say, the official number… like, what does it tell us, right? It tells us which neighborhoods and whose homes police are sent to, which laws they enforce, which people they choose to arrest. It tells us who it is they’re actually here to protect, and who they’re here to punish.

JAMES: So in the case of immigrant communities, you might see vendors ticketed, undocumented folks being detained, drug users or sex workers arrested — these are all crimes, right? But they’re crimes that are pursued and punished and counted in ways that you don’t see in other communities. Say, a wealthy white suburb.

JAMES: And at the same time, in a place like Chinatown, not everyone wants to call the police when they’re stolen from, or dealing with domestic abuse, or being financially exploited, or being harassed. Things that either aren’t crimes, or crimes police don’t have a good track record in helping out.

CATHY: Which, OK, that’s why there’s such a range of opinions about whether to trust the system, or whether to look for alternative solutions.

CATHY: And that brings me back to where we started this episode — with Patrick and Rochelle.

CATHY: When we left off, they had just stopped a bunch of local restaurant workers from beating a Black man, who had thrown a rock at their window and verbally harassed them.

CATHY: Their friends called the cops, who showed up in minutes. It was chaos until a Chinese-speaking officer showed up.

CATHY: The aunties and uncles cooled down, and Patrick thought: “Great. Mission accomplished.”

CATHY: Then, the cops arrested the man. And the shouting match Patrick had just finished with the aunties and uncles was replaced by another shouting match — this time with one of his younger friends, from the crab boil.

CATHY: She wasn’t happy that her own group of friends had called the cops.

Patrick: She was mad that the cops was called, how the guy had to be arrested over a broken window And she was she was like, “He's going to get killed by the system. He's going to get killed by the cops.”

Rochelle: She kept saying that we cared about property more than a person's life, and I think when I heard her say that it —

Patrick: I got super triggered.

Patrick: That's when she goes, “He's going to get killed by the police.”

Patrick: I'm like... “Well, you didn't do nothing when the aunties, uncles are beating down or have you didn't try to stop. You were just there watching, you know? You didn't do nothing yourself.”

Patrick: “Like, we stopped them from trying to kill this person. Like this was the best scenario in the worst situation.” I hate to say it, and she got really mad at me and she just stormed off, you know?

Rochelle: I mean, I felt the frustration that your friend was feeling, but then I also was feeling the frustration of well I don't want anyone to get hurt right at this moment.

Rochelle: It really made me think about, well, okay, what are those in between steps that need to be taken before we can say, “Okay, we don't want to call the police”?

CATHY: Before going any further here... we did check up on what happened to the man who threw the rocks.

CATHY: The city charged him with criminal mischief for breaking the store windows — and with criminal possession of a weapon, because he had a pocket knife on him when he was arrested.

CATHY: He’s waiting for a court date to defend against those charges.

CATHY: No charges were brought against the aunties and uncles.

CATHY: So Patrick and Rochelle were left to sort out what their decisions meant, and what else they could be doing, to create different options.

Patrick: I'm very stuck when it comes to stuff like that.

Patrick: Cause especially in China, Chinatown we seen what over-policing does to us. We also see what not enough policing does to the community as well, you know?

Patrick: I know that the system is flawed, but you got to change everyone around you. You gotta start this local, you know. Cause there's still part of the community whether you like it or not.

Patrick: It puts more work on all of us to try to make this happen.

Rochelle: Yeah.

Cathy: Well, I'm sure you've heard that NYPD has this new task force specifically about anti-Asian hate crimes.

Patrick: I mean it's announced, it's created. But will it work? That, only time can tell.

Rochelle: Mmhm. And I think also, It's getting folks to even trust the police to want to report anything. If they don't know that this task force exists, and they also don't report crimes that are hate crimes that happen against them, then what is the use of increasing police force?

Rochelle: But at the same time, I think that something that I've been really learning from this what happened on Friday is that… we talk about defunding the police and we talk about community strategies, or community safety.

Rochelle: But when but when it's a community that is so diverse, they haven't had the chance to build up this system of community safety and coordinate a system that is about looking out for each other. And —

Patrick: There's no lines of communication. That's what's really hurting everything.

Patrick: We're going to hold the cops accountable, doing their job and taking care of it.

Patrick: The same thing, we were de-escalating and getting yelled at by the aunties uncles, but we came back to them explaining it to them.

Patrick: And they finally like relaxed and they saw, and that they were appreciative of what we were trying to do.

Rochelle: Not only hold them accountable but also to keep them safe, too, because if they had gone ahead and really messed this person up, they too would also end up in jail.

Patrick: What they were explaining to me, it was like, “You can't let people pick on you. Uh, you know, for being Asian, like you can't let you know, you gotta stand up, fight back.” I get that, but... I’m like, “It’s not worth a life for it!”

Patrick: And it's hard for them in their generation to change. That's why we gotta slowly work with them and communicate with them more, but they do understand where we're coming from and they appreciate that.

Patrick: But at the same time, they grew up during a time, they were always pitted against each other.

Cathay: So Patrick, we've done some reporting also on the Chinatown Block Watch here in Manhattan.

Patrick: Yeah, they're always at my store. (laughs)

Cathy: Oh yeah?

Patrick: That's where they meet up all the time.

Cathy: Right, right.

Rochelle: Patrick has stools for them to sit outside.

Patrick: Yeah.

Cathy: Do you personally appreciate having them around your store? Your neighborhood?

Patrick: Yeah! I do, cause it gives them something to go (laughs)

Rochelle: (laughs)

Cathy: (laughs) I'm sure they appreciate your, (laughs) your store.

Cathy: So, we haven't found any, you know, any real sort of concrete evidence that shows what kind of difference they're making in stopping hate incidents.

Cathy: Do you think otherwise? And what do you think that they are good for?

Patrick: They're good as a symbol. That it doesn't hurt to speak up. For people to see, “Oh we're here watching out for you,” you know?

Patrick: It's like, if you don't think you could call the cops or you can't speak to them, you could speak to us and we could do that for you.

Patrick: Like, they're doing something to be more part of the neighborhood or getting to know the merchants that they say hi every week, you know?

Patrick: All it takes is a "Hi," you know sometimes. A “hello.” And that's where it starts. That's where you build a bond and a relationship.

Cathy: It sounds like they're, they're actually increasing that kind of communication that you were talking about.

Patrick: Yes. Even though sometimes we don't agree with each other, we still need to find a way that we could find a way to talk to each other.

Rochelle: Yeah, and I think that what I've really learned from living here in Chinatown is that there you can disagree with people all you want, but you — if you live in the neighborhood you still have to see them every day. You still have to, you have to see them across the street, you run into them everywhere, so... you have to find some sort of common ground, because you're going to have to keep seeing them.

MUSIC starts

Rochelle: The guys who run the Blockwatch are very like macho, but they have a soft spot.

Patrick: They're still, like, amazing people.

Patrick: Like they really care for the neighborhood and community.

CATHY: Next time on Self Evident, we’ll hear from voices who are going beyond task forces and police reports and hate crime laws, to fill in those missing steps that Rochelle was talking about, to keep our communities safe.

Sammie: I don’t think that hate crime legislation will save anybody, frankly.

Sammie: Hate crime legislation usually does not lead to a feeling of actual safety and wholeness.

CATHY: Today’s episode was produced by James Boo, with help from Prerna Chaudhury.

JAMES: Sonia Paul was our field producer. Julia Shu was our story editor, and we were mixed by Timothy Lou Ly. Our theme music is by Dorian Love. And our Community Producer is Rochelle Kwan.

CATHY: Thanks to Rochelle, Patrick Mock, Karlin Chan, Max Leung, and Leanna Louie for sharing their stories with us.

JAMES: And big thanks to Think Chinatown, Jasper Yang, Alice Liu, and Nancy Law, for collaborating with us to survey Chinatown residents in Manhattan and San Francisco.

CATHY: We really want to hear what you think about this episode! Please email your thoughts to community@selfevidentshow.com.

JAMES: And if you want to support this new season, don’t forget to write us a good review on iTunes, or follow us on social media — at self evident show.

CATHY: Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. This episode was made with support from the Solutions Journalism Network, and from the National Geographic Society’s Emergency Fund for Journalists.

CATHY: I’m Cathy Erway. Let’s talk soon. Until then, keep sharing Asian America’s stories.