Episode 001: Whose Dream Is This, Anyway?

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

What does it mean to be excluded from the American Dream? Two stories, set 100 years apart, explore this question from the perspective of immigrants who think they’ve made it in America, only to find out that their dream comes at a cost.

Share your thoughts

Do you have a story about feeling excluded from the “American Dream”? Where or when in your life have you felt most like you belonged? Email your story to community@selfevidentshow.com or share with us on social media @SelfEvidentShow, with the hashtag #WeAreSelfEvident.

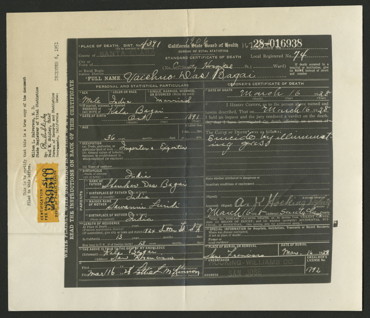

Images of Vaishno Das Bagai courtesy of the South Asian American Digital Archive

Resources and Recommended Reading:

Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-8255 (the Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for you or your loved ones, and best practices for professionals).

History of Angel Island Immigration Station, by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation

History of “Race, Nationality, and Reality” (including more about the Supreme Court decisions that declared only white people could be U.S. citizens) at National Archives

Primary Sources chronicling the life of Vaishno Das Bagai, preserved by the South Asian American Digital Archive

The Making of Asian America: A History by Erika Lee, published by Simon & Schuster

“Escape From Los Angeles: White Flight From Los Angeles and Its Schools, 1960-1980” by Jack Schneider, for the Journal of Urban History

“The Court Case That Forced OC to Stop Ignoring Its Homeless” by Jill Replogle, for LAist

Public Record of Irvine City Council Emergency Town Hall Meeting to discuss the proposal to place an emergency homeless shelter in the Orange County Great Park

Public Record of Orange County Board of Supervisors Meeting to discuss the proposal to place emergency homeless shelters in Huntington Beach, Irvine, and Laguna Niguel

The OC Needle Exchange Program research directory lists many sources of information regarding the public health outcomes of syringe exchanges

“In Fighting Homeless Camp, Irvine’s Asians Win, but at a Cost” by Anh Do, for the Los Angeles Times

“Asian Americans in Irvine Draw Outrage for Protesting Homeless Shelters” by Carl Samson, for NextShark

“Supervisors Defend Their Turf and Criticize Spitzer’s Homeless Warnings” by Nick Gerda, for Voice of OC

“Homelessness in Orange County: The Costs to Our Community,” a research report UC Irvine faculty, sponsored by OC United Way and Jamboree Housing

Executive Summary of research done by the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty

"Student Housing Issues at UC Irvine," a recently released research report by Izzak Mirales at UC Irvine, based in part on data collected by the ASUCI Housing Security Commission.

"Irvine Student Housing Cost and Crowding Under Scrutiny in Report Presented at UCI" by Lilly Nguyen, for the Los Angeles Times

“Not in My Backyard: What the Shouting Down of One Homeless Housing Complex Means for Us All” by Jill Replogle for Southern California Public Radio

Shout Outs:

Erika Lee and Samip Mallick helped us connect with Rani Bagai.

Brandon Morales, Mike Carman, and Molly Nichelson helped us report our story about homelessness in Irvine, California. Izzak Mirales composed the Housing Security study at the University of California in Irvine.

Anne Saini and Jill Replogle graciously consulted with our team on these stories.

We received feedback on this episode from Aileen Tieu, Aishwarya Krishnamoorthy, Akira Olivia Kumamoto, Alex Wong, Alicia Tyree, Anish Patel, Chris Lam, Emily Ewing Hays, Erica Eng, Irene Noguchi, Jen Young, Jennifer Zhan, Jon Yang, Jonathon Desimone, Kelly Chan, Kevin Do, Lynne Guey, Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello, Marvin Yueh, Mia Warren, Rebecca Jung, Robyn Lee, and Tommy Tang.

This episode was made possible by the generous support of Stefan Mancevski and the rest of our 1,004 crowdfund backers.

Credits:

Produced by James Boo, Cathy Erway, and Associate Producer Kathy Im

Additional reporting by Anthony Kim

Edited by Cheryl Devall and James Boo

Tape syncs by Mona Yeh and Eilis O’Neill

Production support and fact checking by Katherine Jinyi Li

Editorial support from Davey Kim, Alex Laughlin, and Julia Shu

Sound Engineering by Timothy Lou Ly

Theme Music by Dorian Love

Music by Blue Dot Sessions and Epidemic Sound

Sound effects by Soundsnap

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

About:

Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Season 1 is presented by the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM), the Ford Foundation, and our listener community. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP.

About CAAM: CAAM (Center for Asian American Media) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to presenting stories that convey the richness and diversity of Asian American experiences to the broadest audience possible. CAAM does this by funding, producing, distributing, and exhibiting works in film, television, and digital media. For more information on CAAM, please visit www.caamedia.org. With support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, CAAM provides production funding to independent producers who make engaging Asian American works for public media.

Transcript

CONTENT WARNING: This story includes an act of suicide. It’s not graphic, but it’s part of the story.

Cathy: The story of an immigrant achieving the American Dream is something we’ve all grown up with. But what happens when you wake up -- and realize the dream doesn’t include you?

Sound: Seagulls, steamship horn, trolley bell

Cathy: In 1915, a businessman named Vaishno Das Bagai boarded a steam ship with his wife and children. They were from Peshawar, which today is a city in Pakistan. But back then, Peshawar was part of India, and India was a colony of the British Empire.

Cathy: His granddaughter, Rani Bagai, has become a kind of historian — not just for her family, but for the American history reflected in her family’s journey. Starting with her grandfather’s arrival to San Francisco:

Rani: A newspaper reporter happened to meet them and said, "Wow! Here's an Indian family!" as they as they came off the ship, literally. You know, no one had ever seen a woman with a nose ring before uh, and very few Indian families, and it was quite the thing, so their photo and story was kind of splashed across the headlines of the newspaper.

Cathy: Back then, South Asian immigrants made up less than 1% of 1% of the country. This wasn’t an accident, and most newspaper headlines weren’t so kind.

Cathy: So the first person Vaishno spoke with in America was an immigration officer who had the power to accept him, deport him, or detain him indefinitely. The officer interrogated Vaishno, asking him to prove that his family wouldn’t be a burden on the country. So, as Rani tells it, he told the officer:

Rani: "I came to America because of your freedoms. I came to America because there is opportunity here, and I want to use that opportunity to educate my family. I want to start up a business, and to show you I can do that, I brought all these funds with me, in gold.”

Music: Self Evident theme song

And when he said that, the immigration officer's attitude immediately turned from being very stern to, being very different, and his response was "Welcome to America!”

Cathy: This is Self Evident, where we challenge the narratives -- about where we’re from, where we belong, and where we’re going… by telling Asian America’s stories.. I'm your host, Cathy Erway.

Cathy: And today we have two stories, 100 years apart, showing how the American dream sometimes misses the thing we need most.

Cathy: Our first story follows an Indian American, who found himself tragically stripped of everything he worked to achieve...

Rani: He said: I did everything right, I did everything you asked of me... And more.

Cathy: And our second story takes us to one of America’s most Asian cities today, as it’s confronted with a decision! About who belongs in their town.

Parrisa: It just seemed crazy that they were going to put the biggest homeless encampment in all of Orange County in the middle of the safest city in America.

Cathy: But first, back to San Francisco, and Vaishno Das Bagai. Here’s his granddaughter, Rani.

Rani: He considered himself to be just like every other hard-working American person, and he thought America was really the place for him and his family.

Cathy: Vaishno spoke fluent English, and he had a penchant for dressing to the nines in three piece suits. So while more and more Asian immigrants were being turned away at the border, Vaishno’s wealth and education and charm helped him get naturalized.

Rani: He used his citizenship to um, you know to have all the privileges and and things that we all take for granted — to go buy property, to go enter into business contracts.

Cathy: So Vaishno opened a store on Fillmore Street, and started an import-export business. Then he bought a HOUSE! in Berkeley, California.

Rani: Being able to buy a house, um, you know, I think made him feel established made him feel like, you know, literally, "I'm a first-class citizen.”

Sound of an old truck driving down a road

Rani: They moved out of their rented home, drove up to the house.

Cathy: But when they arrived —

Sound: Knocking on locked doors, trying to get in

Rani: As far as I understand, the neighbors came our. Locked the doors or maybe had the locks changed on the doors of the house that they were going to buy -- that they they did buy, actually, it was already bought and paid for!

Rani: And my grandmother was just shocked, of course, as you might imagine, taken aback. She said, "Well, I don't want to live here. I don't want to live in a place where you know, people are like this like what if they do something to our children?" So she told Vaishno, "No. We've we've got to go.”

Cathy: The Bagais relocated to an apartment just above Vaishno's store. And for a while, things seemed to smooth out.

Sound: A gavel strikes several times

Cathy: But in 1922, the Supreme Court declared that Japanese people couldn’t become citizens because they weren’t white.

Cathy: In 1923, the Court did the same thing to Indian Americans.

Cathy: Then they went after the Asian Americans who were citizens already.

Rani: There were about 65 or 70 other Indians like my grandfather, Vaishno, who had been granted citizenship, who had like he had, you know bought property or started businesses. They were contacted and told their citizenship had been nullified. It was now voided.

Cathy: So now, Vaishno wasn’t a citizen. On top of that, other racist policies meant to stop immigrants from competing with white land owners made it impossible for him to keep his property.

Cathy: And if Vaishno tried to visit his family in India, he would never be allowed back into the States.

Rani: He felt trapped, and he became very embittered, very depressed...

Rani: ...What he decided to do was buy insurance policies and really kind of methodically figured out, "All right. I do want to provide for my wife, my children, so I want to leave them comfortable."

Rani: He gave my grandmother a pretext that he was going to San Jose on business. He went and checked into a rooming house. He paid, uh, a month's rent in advance. And then he that night…

Sound: A metal nib pen writing briskly on paper

Rani: He sat down and wrote several goodbye letters.

Rani: And one of the letters was actually addressed to the San Francisco newspaper, and it was kind of a speech that he wrote saying: “I am taking this act this symbolic act of taking my own life in protest of what America has done to me I tried to fit in. I did everything right, I did everything you asked of me... And more.”

Rani: “And yet, you deny me. You know, where can I go? What can I be? What is... What is left for me?”

Sound: Paper is folded and put into an envelope

Rani: He, um, basically turned on the gas, and he was found the next day… but it was too late.

Cathy: Today, Vaishno’s granddaughter, Rani, lives a really full life. Her grandmother, Kala, and her dad, Ram, got that insurance money, stuck it out in California, and persevered. As Americans. Despite the many struggles along the way, they found new neighbors, who embraced them for who they were. And they eventually gained the rights that Vaishno was denied.

Cathy: I asked Rani what pushes her to share this story today. And she pointed out something that people don’t always mention when they talk about making it in America.

Rani: The way I see the American dream is that you can come from anywhere... no matter what class, what ethnic group, na-nationality... that you can be a member of American society and feel like a member and make your way. Be able to make your way in it without being crushed.

Rani: I think my grandfather's story kind of told me the importance of one's community. Of feeling like you have a place in it.

Cathy: So today, do we see that kind of community? And where do Asian Americans fit into it? We’ll find out after the break.

Cathy: I'm Cathy Erway. This is Self Evident.

Cathy: America looks a lot different today than it did in the 1920s. But we still face a lot of questions about who has access to the American Dream — especially when it comes to where we live, and who belongs there. One thing that HAS changed? Is Asian Americans today might find themselves on both sides of the fence.

Cathy: To get into what we mean by that, I'm here with James Boo, one of our producers. He’s been reporting in Irvine, California.

James: Hey, Cathy!

Cathy: Hey! James, you’re from Irvine, right?

James: So, Irvine is in South Orange County. And I grew up half an hour away. Shout out to Hot Topic at the Brea Mall, where I bought several overpriced punk rock t-shirts when I was 15.

Cathy: Haha, I’m sure they appreciate that. But there’s more to Orange County, and Irvine, than shopping malls, right?

James: Well, Orange County is home to a lot of Asian Americans. And Irvine is one of the biggest cities in America with a large Asian population -- hovering between 41 and 46% over the past few years.

Cathy: I gotta ask, what’s it like to grow up in a place that's so Asian? Because where I grew up in New Jersey, we didn’t didn’t have that. I mean, I didn’t know anyone else who was Taiwanese American. And when I was younger, my family would make trips into Manhattan just to get dim sum and other food...

James: OK, so not to disappoint you too much, but… I didn’t come up in one of the legendary Asian enclaves you’re thinking of. The Orange County towns that I knew, especially in the 80s, were still culturally white spaces. With lots of first gen families — like mine — kinda tucked in there, working their way up the economic ladder. And going after the resources that white flight had pulled away from cities and into the suburbs during the 60s and 70s.

James: And my family also made those special trips. Like, my parents would drive us back into Los Angeles just to have Korean Chinese food.

Cathy: I see, so it took a couple generations to be able to see and touch -- and taste! that cultural shift in the suburbs.

Cathy: And the big jump in Asian Americans living in Irvine? That’s a recent thing, too?

James: Yeah, especially over the past 20 years.

Music: Hand percussion beat

James: So, Irvine is what’s called a master planned city, and it’s very strictly designed to be like a collection of villages that’s the perfect environment for families. It’s ranked by the FBI as the safest city for its size, a recent study named it the fiscally healthiest city in America, and the schools are great.

Cathy: I can see how that would be a really attractive place for immigrants — or really anyone, trying to get their kids a leg up.

James: You know, there’s actually an imitation suburb in China called Sun City -- which is basically Irvine reimagined as an America-town just north of Beijing.

Cathy: So if you’ve got a house and a yard and great dim sum down the street, then you’ve really achieved the American Dream, without having to give up your cultural roots.

James: That’s what a lot of Irvine residents felt was under threat when this fight broke out in March of 2018.

Broadcast news clip: The fight over where to move the homeless in Orange county is heating up. Hundreds of Irvine residents are saying no to the neighbors the county is considering putting here as it works to handle a persistent homeless problem.

James: Orange County has been struggling to manage homelessness for years. So what happened is, the County Board broke up two shanty towns, where upwards of 1,500 unsheltered homeless people were living just down the street from Disneyland and Angels Stadium.

James: And all of a sudden, everyone had to answer a question they’d been avoiding: Where do all these people belong?

Broadcast News Clip: What started out this week as an idea to create three temporary shelters in Huntington Beach Laguna Niguel and here in Irvine turned into a counter proposal to put all four hundred homeless people on this land across the street from Great Park.

James: I met Parrisa Yazdani, who was a leader in Irvine’s pushback against this proposal. She lives down the street from the Great Park, and met me there to walk through it.

Parrisa: we're just crossing the street and we're about to touch the Hundred Acres that they were going to put, um four to seven hundred homeless people in a camp — OH MY GOSH THERE'S A SNAKE.

Parrisa's Daughter: Where?

Parrisa: Right there! I haven't seen a snake since I lived in Reno. So right here…

James: Parrisa is a second-gen American with Persian, Japanese, and Native heritage. In some ways she fits suburban stereotypes: nice house, does yoga. In other ways, she defies those stereotypes completely. She’s a single mother with a G.E.D. who runs her own contracting business, and has lots of tattoos. But most of all, she centers everything she does around her kids.

Parrisa: This is a huge family Recreational Park in the middle of a bunch of residential neighborhoods. There's no running water. There's no power here. So they were just going to make a makeshift camp.

Parrisa: In a city that is known for being very safe for families. That's why we pay the extra taxes that no other city pays. That's why we pay the premiums that no other city pays. It just seemed crazy that they were going to put the biggest homeless encampment in all of Orange County in the middle of the safest city in America.

James: As you heard earlier, Parrisa is not from Irvine. She told me she grew up in a much grittier neighborhood in Reno, NV, where she saw a lot of crime and drugs on the street, had friends who were in and out of jail, and didn’t feel like she had a future.

Parrisa: You know, my dad coming here from Iran — he actually came here from Spain, he was living there on asylum until he was accepted into America, and so my dad lived homeless, you know on the streets of Spain while he awaited that, didn't know the language or anything, so... He tried to really push to me that you don't need to be stuck in this type of life. You can get out of it. There is better, you just need to work hard to get out of it.

James: Parrisa left home, and spent the next decade slowly building that better life in California, even starting her own family. But her partner was abusive... to the point where Parrisa started to fear for her life. Once she decided to leave him, she made it a goal to live in Irvine, where she could give her daughter a better, more predictable life than the one she had.

Parrisa: With my daughter's dad. I mean he had it all he had a home he had a business you had a you know, his truck fully loaded. He didn't come from that but he built himself a great life and... Within about a year and a half of us breaking up...he got addicted to drugs. nd within six months he had gone from sober to full-on homeless and addicted to meth.

Parrisa: He abandoned his daughter to live on the streets and to do drugs, so my immediate thought was, "Holy crap. They're going to put 400 people just like him right across the street from my home exactly what I was moving away, from exactly what I've been trying to protect my kids from they were going to put 400 of them across the street from my home. And that terrified me.

Sound: Parrisa types as she speaks

Parrisa: I'm not the best typer. My daughter is think is better than me...

James: Parrisa started a Facebook Group called "Irvine Tent City Protest." She figured 20 people would join to vent about the news. But word spread quick.

Music: Tense, steady beat

Parrisa: My Facebook blew up with a bunch of requests from people to join the Facebook group, and I noticed they were all Asian. They were talking about it on WeIrvine or WeChat and I guess within minutes there was like 500 people or a thousand people that were like, oh my gosh, and and by like two o'clock that night I had about a thousand to two thousand members.

Parrisa: So we were going to have you know, a meeting one of the clubhouses with snacks and the city ended up calling us Thursday at about five o'clock, and our meeting was going to be at 7, and told us you guys have too much interest in this meeting. There's going to be too many people. The fire marshal will shut you down. We're willing to let you guys have it at the city hall.

Sound: Crowd of people inside Irvine City Hall recite the pledge of allegiance

Irvine resident: The plan to place a homeless encampment on Orange County Great Park is nothing more than another dump job by the Board of Supervisors...

Irvine resident: ...62 tons of debris or more. 400 pounds of human waste or more. 2,290 needles or more….

Irvine resident ...I have never been at a point where I can be afraid of going out, or I will let my children go out without any security or safety concerns….

Irvine resident: ...I chose to live here, buy a home here, raise our son here, because I thought, "Hey, this is going to be a great place to have him running around, meet friends, grow up."

Cathy: OK, so I have to ask: was there a single person in Irvine who was OK with this proposal?

James: No Irvine residents spoke for the proposal at this meeting, but three people spoke in support of homelessness assistance.

James: And one person from the neighboring city of Tustin, a non-profit organizer named Mohammed Aly, did testify in favor of the proposal.

Mohammed Aly: A family died in a van. With two small children because they didn't have shelter. They died of carbon monoxide poisoning apparently because it was cold and they left the heater running. These people are not sex offenders. They're people! They're people! And and and and if you are interested in hearing the truth, since I am the ONLY one here trying to make my point, I invite you to ask me these questions and challenge me on any of the factual or legal arguments that I'm presenting to you. Do you have any questions for me, city council, about what is actually happening on --

Mayor Don Wagner: Hang on.

Muhamed Aly: -- what is actually happening in --

Mayor Don Wagner: Mr. Aly? I will run the meeting. I think it's a fair request. Any questions of my coll - from my colleagues? Seeing none, your time is expired. Thank you, sir.

Sound: Protestors shout “KEEP CHILDREN SAFE!”

James: At the next county meeting, Parrisa and about 1,000 other Irvine residents showed up in 24 chartered buses that were paid for by WeIrvine, a Chinese American company that helps Chinese immigrants get settled and connected in Irvine neighborhoods. They staged this huge protest outside the County building and flooded the chambers to testify.

Cathy: OK, how'd that go down?

James: The County Board of Supervisors basically said, "Whoops! My bad!" and took it all back, and apologized.

James: Parrisa won. And all the people who had come up from Irvine celebrated.

James: But some of the news headlines they saw the next day… were not what they expected.

Cathy: Oh my god, I remember this protest now! But... how did some of those headlines go again?

James: Well, there was one from Nextshark, saying “Asian Americans in Irvine Draw Outrage for Protesting Homeless Shelters,”

Cathy: Oh, right! And that piece from the LA Times, saying, “Irvine’s Asians Win... but at a cost.”

James: Yep. And you know who else remembers those headlines?

Parrisa: I was very very outraged by this. They made this from a community fighting an injustice that we didn't even know was going to be coming to us to... the Asians are finally now speaking up when, no. They're just being neighbors, you know, and the reason why this was so big was because there was people of all races involved in it, you know, it was, it was not just Asians.

James: The Chairman of the Board of Supervisors, who is also Asian American, is also unhappy about this. His name is Andrew Do, and I asked him how he’d write the headline.

Andrew: "Irvine opposes the homeless shelter." There should not be a racial component to it. I think the um, The homeless shelter was basically -- n-no -- was uniformly and universally opposed by all of Irvine, including the city council. And so to spin it only as an Asian issue. Is... I'm gonna go there… it's racist.

Cathy: Okay, I’LL go there too! We see this same kind of pushback in towns all over the country, but I’ve never seen a headline that says, “Local white mob says no to homeless shelter.”

Cathy: It seems like such a little thing, but singling out Asian Americans who’ve made a good life for themselves, and now have the power to make these decisions... feels unfair.

James: So, to keep things in perspective, that article, which we’ll link to in the show notes, went a lot deeper than the headline.

James: There were Asian Americans on all sides of this issue. And this protest really was unique in a couple of ways: First off, a lot of people showed up. More than you’d expect for this kinda thing. Second, that thing about WeIrvine —

Cathy: Oh, the company that organized the buses for protestors?

JAMES — yeah. Well, that kind of thing hasn’t really happened at any other shelter protest in Southern california, either. And this did happen against an ongoing rise in Chinese and Taiwanese immigration into Orange County.

Cathy: Which does underline the point for me, which is: It’s important to dig deeper than just the identity of being Asian.

James: Yeah. So Chairman Andrew Do, who made this proposal, didn’t want his identity to be lumped in with the quote-unquote “Asians of Irvine” because he had a different story. He came here as a refugee from war in Vietnam.

Andrew: There are political immigrants like myself, fleeing communism, who came here empty handed, having to restart our lives, and depended on the assistance of the new society here in America.

Andrew: Whether city or county or state, we have to have a system of care, and the system of care requires that everyone contributes a little bit to that solution. And some cities right now just feel, you know, they have their head in the sand and they don't have a homeless problem. The danger is when we choose to self-select on where we live, and then the flip side of that is to exclude certain demographics that we find less desirable.

Cathy: Wow. “Certain demographics that we find less desirable.” ok, I wanna get into that. But first, let’s take a little break...

Cathy: So, we just heard from Andrew Do, Chairman of the Board of Supervisors, saying:

Andrew: I'm gonna go there… it's racist.

(James repeats this clip out-of-context): It's racist. It’s racist. It’s racist.

Cathy: Hey, that’s not the clip I was thinking of!

James: (laughs) I could do this all day.

Cathy: (laughs) OK, but play the other thing.

Andrew: The danger is when we...exclude certain demographics that we find less desirable.

Cathy: When I hear this, I think we’ve entered a bigger conversation. About who we find desirable for our communiy.

James: Yeah. At first, I thought I was gathering different Asian American perspectives about this protest. But that fight turned out to be full of red herrings.

Cathy: Starting with race. Whether you agree with the proposal, the identity that was pushed hardest in this protest wasn’t being Asian American. It was being a suburban homeowner.

James: Then there was the proposal itself, which, once I looked into it, was really a last-ditch effort, without any real details on how the shelter might be run. That lack of information made it really easy for this conversation to be driven by fear.

Cathy: OK, so once we set aside those things - the race factor, the flawed proposal… what we have left is homelessness.

Cathy: And stigmas about homeless people, and I can hear a similarity in how these folks are being lumped together and rejected. It’s not that far away from how Asian Americans and other people of color are treated.

James: Yeah. I mean, we can’t undo all those stigmas, but we can appreciate the experience of being shut out. And take a closer look at homeless from a different kind of immigrant perspective.

Lydia: Most people who are born in this country don't understand the narrative of somebody coming here with nothing but a dream. I always say I don't even know how I found myself in America. It was by the grace of God. I didn’t even have a dollar to my name, but I had hope and zeal to go to school.

James: That’s Lydia Natoolo, a public health worker who’s originally from Uganda. At the same time Parrisa’s fight over emergency shelter was blowing up at Irvine City Hall, Lydia was organizing for more affordable housing at the University of California in Irvine. And just like Parrisa’s story, this fight was part of a long road to building a better life.

Lydia: So I came to live in California to live with with a dear friend. But as life has it she told me to leave her house, um, and go find my own space. For a minute. I thought she was joking, but then I realized every day every hour every day, she came back from work. She asked me whether I found a place to go and I realized she was serious about it.

James: Lydia didn’t have any credit, so nobody would give her a lease, even though she had a job.

Lydia: I packed all my belongings which were just two suitcases with my clothes and shoes and books. I didn't have any family member to drive to... And I think the reality of parking your car on a street or at a shopping center, and literally watching other people's lights go out in the buildings where they're sleeping, you know, um… Locking my car and just closing my eyes and praying to God that I wake up safe… No human being should live like that.

James: She lived like that for three months. During that time, she never told anyone what she was going through.

Lydia: Imagine you’re in Uganda. Your daughter calls you that she's sleeping on the street. Imagine that. So I didn't want my mother's heart to be broken. Because also there's a narrative people think America their riches on the street, you just grab money of the trees people don't understand that actually people in America suffer, too.

James: Lydia moved to Irvine to enroll at UCI — which was rated by the New York Times as “The No. 1 U.S. university doing the most for the American Dream.” About half of UCI’s graduates are the first in their family to attend college.

James: So Lydia was overjoyed to be living in this community where everyone around her was on the path to something better.

James: Then she heard that one of her classmates was living out of his car.

Lydia: Many administrators did not want to talk about how they're homeless students on college campuses because we have to keep this perfect face, right?

James: As student body president, Lydia helped found UCI’s housing security commission, which just released a study showing that 8% of UCI students have been homeless, slept on couches, or stayed in abusive relationships to avoid becoming homeless. And around one-third of students have had more than 1 friend at a time sleeping in their living room or garage.

James: The students following in Lydia’s footsteps are now taking their case to the City Council to show the full spectrum of homelessness in Irvine.

Lydia: When somebody says in Irvine there are no homeless people, they are definitely just getting into their cars and going into their beautiful offices and getting into their homes and getting to the garage and closing out the reality. They live in a lie. It's a pretense to think we don't have homeless people in Irvine, because we do. It is a painful reality to know that there is an America that is what it is.

Cathy: Wow. It’s kind of crazy, that Lydia basically had to start a movement... just so the suffering she went through could be counted as real.

Cathy: I mean, there’s research about homelessness, right? Just like there’s research showing that immigration doesn’t cause crime to explode. And in both situations we still have this uphill battle to have a reasonable conversation about what’s true.

James: Oh, for sure. You know, just as I was digging through the studies for this story, my parents saw a local news story about homelessness in LA Koreatown, and they asked me if I knew what the solution was.

Cathy: Oh my gosh. What did you say?

James: I said the solution is giving people homes.

Cathy: Taa daa!

James: Haha, yeah, that was easy, right?

James: Seriously, though, here’s the thing. Most people who experience homelessness... They’re people like you and me, who are just on the brink, you know, middle class or working class, and they’re just one missed paycheck, or one emergency room trip —

Cathy: — or one bad breakup, or one family tragedy, or one bad decision —

James: — yeah, just one unexpected step away from losing their home.

James: The leading cause of homelessness in Orange County isn’t drug addiction. It’s not mental illness. It’s that people can’t earn enough to pay the rising cost of rent. So the research supports a “housing first” approach, which means: If you keep people in an affordable home, it’s a lot easier and cheaper to help them get on the right track and solve the big-picture problem.

Cathy: Right, as opposed to making housing like... a reward that you only get after you win at life.

James: Exactly. But when I said this to my parents, my dad immediately said, “That’s not fair.”

Cathy: Yeah.

James: “What about all the other people in that neighborhood who paid for their houses?” “Why does this guy get a free house?” And like two minutes later, we’re having this insane, hypothetical, ideological argument, where he’s telling me this is not a socialist country… and this is a pretty typical response. I tried to explain the research… but that’s not what people want to talk about. People want to have this moral conversation about whether you earned what you have. And we put so much effort into protecting that ideal of meritocracy, of self-made success.

Cathy: Yeah, and it’s tempting for me, as the child of an immigrant, to embrace that dream, of making it in America.

James: Right. In some ways, the people with the biggest stake in that narrative are us.

Cathy: Right, the product of that dream, from our parents.

James: Yeah!

Cathy: OK, that’s true, but we don’t all share the same journey, as Asian Americans or as immigrants. So it’s OK for us to stop romanticizing this piece of the American Dream —

James: — or the perfect, successful America town, where hard-working Asian Americans are always winning —

Cathy: — But AT A COST.

James: OH NOOOOOOO. (laughs)

Cathy: (laughs) But getting back to Irvine... James, you started looking into this whole thing over a year ago. What’s up with Irvine today?

James: The City of Irvine hasn’t done anything to build new emergency shelters, and along with four other cities in Orange County, they’re being sued over this issue.

James: But Parrisa -- the woman who kicked off those protests -- is pitching her own proposal. She’s trying to get the city and a local non-profit to collaborate on a new shelter in Irvine for families, women, veterans — and their pets.

Parrisa: I'm hoping that because it is not near homes, it is not near schools, it is not going to negatively impact the community.

James: and she’s unapologetic about keeping the Great Park exactly the way it is, and keeping anything unknown away from her kids.

Parrisa: ...which is why I've been very active in trying to find a different spot, you know, within Irvine, that is acceptable to the residents that is acceptable to you know, everyone in the majority of everyone because obviously not everyone is going to be happy with it.

James: Today, a lot of cities in Orange County are building emergency shelters for the first time. And there is a LOT more to this crisis than these shelters. But it’s an important place to start talking about who belongs where, and what we’re willing to do in our own backyards.

Parrisa: You know, the homeless families and things like that it ate at me. So I tried to kind of turned a blind eye to it. Because I wanted to just focus on my family. but I did not see it balloon into what it has in the last five years. And that's because I kind of isolated myself in Orange County and in Irvine these last, you know several years.

Parrisa: I feel bad that I kind of turned a blind eye to it. But now it's like -- I would like to see this happen, so that way, we can say, “Look. We have done it. We do care. We’re not these heartless people that have -- we’ve been made out in the media to be. I'm hoping that we can get this resolved for Irvine.

Music: Pensive and funky instrumental beat

Cathy: Sometimes, an American dream shattered is a wake-up call. Every one of the people we met today was on the path to making their dream a reality. But most of all, they were looking for a place where their dream could be shared — where you’re embraced and given a chance, no matter where you’re from. Whether we show up with a suitcase full of cash or nothing BUT a dream, we all want to find that community. And once we’re there, we all have to decide who else can be a part of it.

Cathy: Next time on Self Evident, we’ll ask: In the year 2019, what does the term “Asian American” even mean?

Self Evident Community Panel Member: “I think most people think of East Asians and as a Pakistani American I obviously don’t fit that”

Self Evident Community Panel Member: “I generally do identify with the term Asian American, but I just prefer to be more specific and use Cambodian American”

Self Evident Community Panel Member: “I tend to get more granular when I’m talking to someone who’s also Asian American”

Cathy: To find out, we’ll share stories from our listener community and chat with a researcher who’s been investigating this label we sometimes take for granted.

Cathy: This episode was produced by James Boo. And me, Cathy Erway. We were edited by Cheryl Devall and mixed by Timothy Lou Ly.

James: With reporting by Anthony Kim, production support from Eilis O’Neill, Kat Li, and Mona Yeh, and editorial support from Davey Kim and Alex Laughlin. Our theme music is by Dorian Love.

James: Special shout out to Anne Saini and Jill Replogle for their guidance and support in the making of this episode.

Cathy: And a very special thank you to Associate Producer Kathy Im, Stefan Mancevski, and the one thousand and four crowdfund backers whose support made this season possible.

Cathy: We want to hear from you! Let us know what you thought about this episode on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, @selfevidentshow.

James: You can also e-mail your thoughts to community@selfevidentshow.com.

Cathy: Self Evident is a new show! Help us get the word out by recommending this episode to your friends, family members, and co-workers. You can also support us by rating and reviewing us on Apple Podcasts, or wherever you’re listening.

James: And don’t forget to check out the show notes for links to the records and stories that Rani Bagai has shared from her family history, along with research on the facts, myths, and solutions regarding homelessness.

Music: Self Evident theme song

Cathy: Thanks to our amazing advisors and all the members of our community panel who gave us feedback on this episode before it aired. If you want to be a part of our storytelling process, OR if you want sneak peeks and behind-the-scenes content, sign up for our newsletter at selfevidentshow.com.

Cathy: Self Evident is a Studiotobe Production. Our show was incubated at the Made in New York Media Center by IFP. This season is presented by the Center for Asian American Media, with support from the Ford Foundation, and you! Our listeners.

Cathy: Our show is managed by James Boo and Talisa Chang. Our Senior Producer is Julia Shu. Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda. Our Audience Team is Blair Matsuura, Joy Sampoonachot, Justine Lee, and Kira Wisniewski.

Cathy: I’m Cathy Erway. Let’s talk soon! And till then, keep on sharing Asian America’s stories.