Episode 029: Say Goodbye to Yesterday

Subscribe today on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Pocket Casts, Radio Public, Spotify, Stitcher or TuneIn.

About the episode:

Amidst the ongoing crush of anti-Asian violence in America, Producer James turns to a personal source of restoration: ska music (yes, that ska music).

When he was a teenager, the do-it-yourself ska scene — and an indie record label called Asian Man — taught him to take racism seriously, embrace the road less traveled, and never wait for anyone else’s approval to be himself. But as James starts connecting with all of the Asian American ska fans he’s met over the past few years, he also starts to question how much his own memories are wrapped in a black-and-white-checkered blanket of nostalgia.

Eventually, these connections all lead to Mike Park, Korean American founder and still-only-employee of Asian Man Records — and Jer Hunter, a younger Black and queer musician who’s carrying the torch for ska music as a home for anti-racist activism.

And the more these conversations peel away the layers of nostalgia surrounding ska, the more James believes that this oft-misunderstood subculture has something real to offer in a world that can feel like it’s crumbling beneath our feet.

Resources, Reading, Viewing, and Listening:

Don’t forget to take our anonymous listener survey!

WATCH: “Racism in East London,” an episode of the 1970s docuseries Our People by ThamesTV

WATCH: The entirety of Dance Craze, the documentary about 2-Tone that hooked Mike Park (and countless others) on ska music

WATCH: Skatune Network’s life-giving cover of the Koopa Troopa Beach theme from Mario Kart 64

LISTEN: Ska Against Racism 2020, the benefit compilation by Bad Time Records, Ska Punk Daily, and Asian Man Records

LISTEN: SKA DREAM by Jeff Rosenstock

LISTEN: “Five Miles to Newark,” the full-length debut album by Chris Erway’s high school ska-punk band, Taxicab Samurais

LISTEN: Mike Park chats with Charlene Kaye on The Golden Hour podcast

LISTEN: This Is Ska, a weekly live radio show hosted by Middagh Goodwin (archives available)

READ: “Tracing Ska Music’s Great Migration” by Evan Nicole Brown for Atlas Obscura

READ: “The Chinese Jamaicans: Unlikely Pioneers of Reggae Music” by Tranquilheart for Spinditty

READ: “It Came From the Garage: Celebrating 25 Years of Asian Man Records,” a comic by JB Roe

READ: In Defense of Ska by Aaron Carnes

READ: “Skatune Networks’ Jer on Pushing Ska Forward” by Eve Sicks for Reverb.com

READ: “Ska’s New Generation is Here to Pick It Up Pick It Up” by Arielle Gordon for Stereogum

READ: “Ska is Thriving Right Now: Here’s a Look at the DIY Scene That’s Keeping It Alive” by Andrew Sacher for Brooklyn Vegan

Credits:

Produced, written, and sound designed by James Boo

Edited by Julia Shu, with help from Cathy Erway

Sound mix by Timothy Lou Ly

Fact checked by Tiffany Bui and Harsha Nahata

“No Guarantee” written and performed by James Boo, feat. Dorian Love on bass and Chris Erway on trombone, trumpet, and alto saxophone

Ska Dream by Jeff Rosenstock; original compositions for “No Time to Skank” and pickitup” licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Music provided courtesy of Asian Man Records:

“Still Down for Tomorrow” by the Bruce Lee Band

“Signature” and “You Don’t Know” by The Chinkees

“Riptide 28” and “Sultan’s Cross” by Let’s Go Bowling

“David Duke Is Running For President,” “Pabu Boy,” and “Onyonghasayo,” by Skankin’ Pickle

“Mutually Parasitic,” “Achilles’ Dub,” and “Stash” by Slow Gherkin

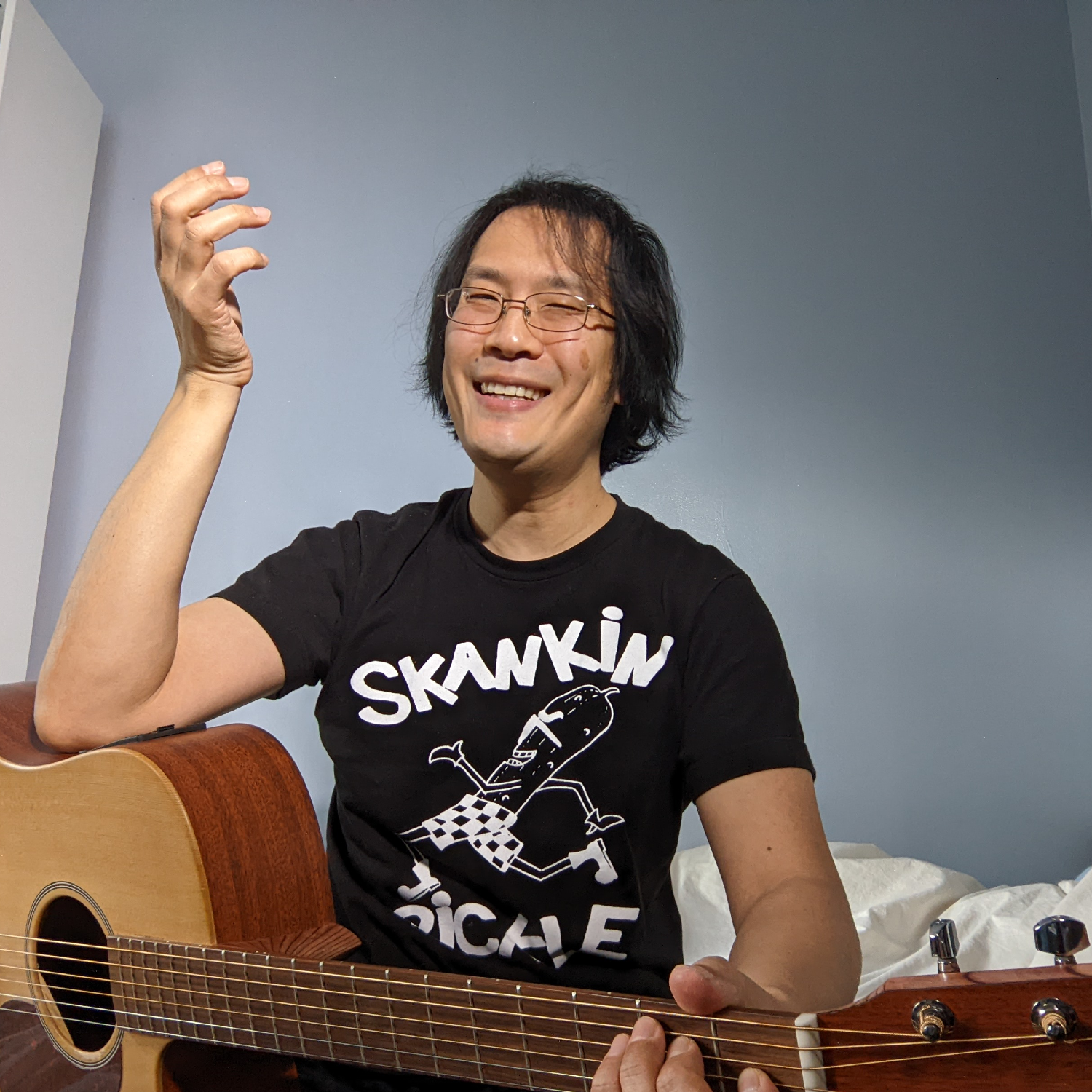

Photos of Mike Park courtesy of Mike Park

Photo of Jer Hunter courtesy of Rae Mystic

Photo of band huddle at Ska Dream Nights by listener Frank Chan

Self Evident theme music by Dorian Love

Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda

Self Evident is a Studio To Be production. Our show is made with support from PRX and the Google Podcasts creator program — and our listener community.

Transcript

Pre-Roll: Listener Survey

JULIA VO: Hey everyone, this is Julia, Self Evident’s Senior Producer.

JULIA VO: Before we start the show, I just wanted to ask you to take our listener survey.

JULIA VO: It takes just a few minutes, it’s anonymous, and your feedback really helps us to figure out what we’re doing next.

JULIA VO: You can take the survey at selfevidentshow.com/participate, or check for the link in our show notes.

JULIA VO: Also — there’s going to be swear words in today’s episode.

JULIA VO: Thanks for listening!

Cold Open

CATHY VO: Hey everyone! It’s Cathy. I’m here with our producer James.

JAMES VO: Yeah, I’ve been wanting to talk to you about something really great that happened to me towards the end of 2021.

SOUND: Concertgoers mill about as they wait in line to get into a music venue

JAMES VO: So it was the day after Thanksgiving, and I was in line with a friend to see Jeff Rosenstock , who’s one of my favorite musicians.

JAMES VO: This was the only show I’d been to since the pandemic started. It was freezing cold. I’d barely left my bedroom for like three months.

JAMES VO: And we were starting to get news about this new thing called Omicron —

CATHY VO: But you didn’t let that stop you.

JAMES VO: There was NOTHING that would have stopped me from going to this show.

JAMES VO: Because Jeff Rosenstock makes punk music. But! He also has a long history of being in SKA bands.

SOUND: Jeff Rosenstock and his band take the stage

Jeff Rosenstock: What’s up, everybody?

Audience: (Cheers)

JAMES VO: And this was a special leg of the tour called SKA DREAM NIGHTS , where the band played SKA renditions of all their newest songs.

Jeff Rosenstock: (screaming) SKA DREAM LET’S FUCKIN GOOOOOOOOO

Audience: (Screams and cheers)

SOUND: The band plays “No Time to Skank,” which begins with a big blaring horns section, then the live band music ducks under Cathy and James

JAMES VO: (laughs) Just listen to this. Lis, listen to this. This is my people.

CATHY VO: Amazing.

JAMES VO: Hundreds of ska fans dancing in the apocalypse.

CATHY VO: Amazing. (laughs) Oh my goodness, that’s like your ska dream, come true, forreal.

JAMES VO: Oh, yeah.

JAMES VO: I’m just grateful for that feeling — you know, when you’re going through tough times, and you know the exact place that you can go to work it out?

JAMES VO: You know, maybe for some people that’s the… gym? Uh, definitely not me, I don’t go to the gym. I go to see ska bands. (laughs)

SOUND: The concert recording fades out under Cathy

CATHY VO: (laughs) OK, so if you’re listening to this, and you don’t know what in the world we’re talking about, you might remember some names of ska bands that had hit singles in the 90s — like Reel Big Fish, or the Aquabats, or the Mighty Mighty Bosstones.

JAMES VO: Rest in peace.

CATHY VO: So I’ve heard people refer to ska music as “fast reggae with horns”...

JAMES VO: (chuckles)

CATHY VO: …which I know isn’t 100% accurate. So let me just get that out of the way. It’s something — it’s something I’ve heard people say

JAMES VO: Yeah, I mean, we can get into musical details later, but here’s one example what that 90s ska music sounds like — and Cathy, you might recognize this one.

MUSIC: “Sweats” by Taxicab Samurais begins

CATHY VO: (laughs loudly) Oh my God, yeah!

CATHY VO: Yes, that is uh… (laughs)

JAMES VO: I pulled this little gem out of the New Jersey Pop Punk Archives.

JAMES VO: This band is called Taxicab Samurais , and the trombone you’re hearing in this band is actually Cathy’s brother.

CATHY VO: Okay, this brings up memories.

CATHY VO: We would go see them at these underground shows with all these other punk and ska-punk bands, with big crowds of teenagers, and it was always at these veteran halls and churches, and the energy was… I think it was like your SKA DREAM concert, like, a hundred percent.

CATHY VO: It was through the roof, and I remember being elbow to elbow with people who were just dancing and bouncing, and jerking around…

CATHY VO: I don’t know, the intensity of the fans — it’s really something, at these shows.

MUSIC: "Sweat" by Taxicab Samurais end abruptly and loudly

JAMES VO: It is. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I’m a ska fan, and your brother is a ska fan.

CATHY VO: Oh. Like, why?

CATHY VO: Is there something special about ska and Asian American fans?

JAMES VO: Um, okay, so you are aware that I wear a lot of ska band t-shirts, right?

CATHY VO: Yeah. I am.

JAMES VO: So one of the reasons I do that is that whenever I’m in a public place — like, especially if I have to go to a conference, which I don’t really like — the ska people will find me.

JAMES VO: And I’ve specifically met so many Asian American ska people over the years, just by wearing these t-shirts.

CATHY VO: Wow! Amazing!

JAMES VO: Yeah, I’m talking South Asian, Southeast Asian, East Asian, Asian adoptees, straight folks, queer folks, men, women, nonbin — like, every kind of Asian American…

JAMES VO: And so I started asking all these Asian American ska fans, who mostly found the music in the 90s and 2000s:

JAMES VO: Why is this music, which has no roots in any Asian country, such a big thing for us?

MUSIC: “Riptide 28” by Let’s Go Bowling begins

Daisy Buranasombhop: I wanna dance to the music! And that is what was great about ska, like —

Kira Wisniewski: — everybody's moving and you don't have to dance with anyone in particular because you're dancing with the entire room.

KW: And so that's something that makes it really kind of beautiful, too.

Raman Sehgal: This is crazy. This many people, having this much fun… There’s a HORN section —

Timothy Lou Ly: God damn! Like, you can do that? You're creating new shit that I've never heard? That first stumble into the unknown is exciting.

Arvin Temkar: A lot of it is made by people who are, like, kind of misfits or outcasts… I just thought ska was a more welcoming kind of genre.

Steph Ching: What I liked about the scene too, was — it was a subculture, but it was a subculture without… elitism?

DB: It was cheap. It was accessible. It’s a bunch of kids playing music at that point, right? Everybody was in high school, being in love with the music they were playing.

Mitchell James Cho Barys: I'm adopted. My parents never really exposed me to, like, other Asian folks...

MJCB: Playing in bands, you meet people from other areas. So I just, like, have this really amazing memory of, like, meeting, two Korean adoptees, and they became my, like, posse, you know?

Chris Erway: And it just felt so amazing that we could do this and that anything was possible, you know, there was no gatekeeper saying, “Oh, you can't book this. You can't play this music. You can't sing these words.”

CE: What makes ska feel like ska was this idea, that you could make your own music culture.

MUSIC: “Riptide 28” ends

Open

MUSIC: Theme music begins

CATHY VO: This is Self Evident, where we tell Asian America’s stories to go beyond being seen.

CATHY VO: I’m your host, Cathy Erway.

CATHY VO: And today I’m passing the mic to James, who’s taking us into the subculture of a subculture that is Asian American ska fans.

JAMES VO: That's right! And talking to those fans led me to one of the most loved musicians in ska.

Mike: My name is Mike Park, and I am... I'm a father, son, husband, and I guess I'm most well known for running Asian Man Records.

Mike: And… playing ska! (laughs)

CATHY VO: Mike Park! I remember how blown away I was to discover this CD that my brother had. It was called, “The Bruce Lee Band.” It was his band.

CATHY VO: You know, I can’t remember too many of the songs on it, but I definitely remember “Don’t sit next to me just because I’m Asian.”

CATHY VO: I mean, I don’t know, I always thought he was a really under-the-radar figure, but that song definitely had an impact on me.

JAMES VO: Yeah! You know, I feel like most stories about Asian people in pop culture are about making it to the big stage…

JAMES VO: But Mike Park showed me how powerful it can feel to be part of something small, to build your own stage.

JAMES VO: And since Mike is still making new music, I was really excited to talk to him.

JAMES VO: And also, I talked to Jer Hunter, a younger generation ska musician — to figure out what’s truly special about this thing called ska, and how to stop nostalgia for the past from getting in the way of our future.

MUSIC: Theme music ends

Segment 1: Generations

CATHY VO: So James, I loved hearing from all those Asian American ska fans.

CATHY VO: But they were talking about American ska bands in the’90s and early aughts, right?

JAMES VO: Mmhm.

CATHY VO: So let’s talk about the history of the music. ’Cause I know there’s a deeper there, right?

JAMES VO: Yeah, and I actually think the reason ska resonates with Asian American fans has a lot to do with the history of the music.

CATHY VO: Even though, like you said, the history isn’t tied to any Asian country.

JAMES VO: Yeeeeahhh… (laughs) OK, so let me give this a try…

JAMES VO: In the 1950s and 1960s, ska was actually the first modern pop music of Jamaica.

CATHY VO: Oh! And was it actually called “ska” back then, too?

JAMES VO: Oh yeah, the biggest band of the era was The Skatalites.

JAMES VO: Um, they played this multicultural mix of Afro-Caribbean dance music, folk music, and work songs. And then also 1950s Black American music like R&B and jazz . It all mixed together.

JAMES VO: And because of immigration and indentured labor under the British Empire, there were also some Chinese Jamaicans helping to make this music in Jamaica . Not to mention a huge Indo-Caribbean population throughout the country.

CATHY VO: Okay, so there have been Asian folks in ska since the start.

JAMES VO: I mean, don’t get me wrong. Ska is a Black music, like, full stop. But Jamaica’s also a really multicultural place. I think sometimes people hear that, and they’re surprised by it.

CATHY VO: Mmhm, and what did ska sound like back then? I’m guessing, not like my brother’s ska-punk band… but did those ska bands have horn players, for instance?

JAMES VO: Yeah! But you hear horns in all kinds of music. What really makes the ska sound is the rhythm. So… I’m just gonna grab my guitar here to show you.

SOUND: James picks up an acoustic guitar

SOUND: James plays and sings the opening measures to “Buddy Holly” by Weezer:

JAMES VO: What’s with these homies, dissing my girl?

JAMES VO: Why do they gotta front?

CATHY: (Laughs) Some Weezer, there…

JAMES VO: Yeah, you know — “Buddy Holly” by Weezer is a good example.

JAMES VO: Um, if you listen to it, think about where the bass drum goes, right?

JAMES VO: The beat goes like this:

SOUND: James resumes playing

JAMES VO: ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-three-four —

SOUND: James stops playing guitar

JAMES VO: That’s a really typical backbeat.

JAMES VO: Now, here is the ska beat.

SOUND: James knocks on his guitar and counts out a traditional ska beat while playing an upstroke rhythm,

CATHY VO: Ooooooh, yeah…

SOUND: Then James sings the exact same melody to show the difference in rhythm:

JAMES VO: What did we ever do these guys

JAMES VO: That made them so violent

CATHY VO: Yeah!

JAMES VO: Hoo Hoo, and you know I’m yours…

CATHY VO: (laughs)

SOUND: James stops playing guitar

JAMES VO: (laughs) I don’t know if we can play any more of this song without getting sued.

CATHY VO: (laughs)

JAMES VO: So it’s really like (pause) and-TWO-and-three-and-FOUR-and (pause) and-TWO-and-three-and-FOUR-and …

SOUND: James continues playing guitar

CATHY VO: It literally just makes my head jerk. Like, it’s kinda swingy, and it’s, like, easy to dance to, and I’m, like, jerking around right now, like a chicken.

SOUND: James stops playing guitar

JAMES VO: Like a chicken? (laughs)

CATHY VO: (laughs) It’s, like, always moving, you know?

JAMES VO: Yeah, that’s good, and movement is actually the right word —

CATHY VO: Yeah.

JAMES VO: — because another huge aspect of this music — which I think instinctively clicks with Asian American fans… is that it’s a multigenerational music, and it’s evolved through immigration and integration and people adapting it to where they go.

SOUND: Record stylus drops and a vinyl record starts to spin

MUSIC: “Achilles’ Dub” by Slow Gherkin, heard through a crackling radio speaker

JAMES VO: After World War II, Jamaicans started moving in huge numbers to the UK, uh, to take manufacturing jobs and other manual labor , and they brought the music with them .

JAMES VO: And so then there was a whole generation of working-class Black and White and Indo-Caribbean kids growing up with Jamaican music during the 50s and 60s .

JAMES VO: Then, during the 1970s, when the economy was in really bad shape , there was a surge in British right-wing groups who scapegoated immigrants. Not just Black and brown Caribbean immigrants, but South Asian folks, too .

National Front Party Rally Speaker: We will fight you back, and we will fight you with every bone, every nerve, every feeling, every ounce of blood we’ve got! WE WILL HAVE OUR COUNTRY BACK! ”

(National Front Rally attendees applaud)

JAMES VO: So they were marching through Black neighborhoods with protection from the cops. They were beating up South Asian people in the streets ...

ARCHIVAL: Interview of Bengali Worker for “Our People” by Thames Television

News Announcer’s Voice: Asians have also found themselves in danger, on their way to and from work.

Bengali worker’s voice: They waited until the workers came out, and they were systematically attacked, very viciously.

JAMES VO: And one of the things that happened in response was that a bunch of Black and Brown and White kids got together and formed a new generation of bands that were explicitly anti-racist.

SOUND: “Achilles’ dub” ends and stylus scratches slightly as the vinyl record is halted

JAMES VO: And played ska.

SOUND: Tape cassette enters a deck, and the play button is pressed down

MUSIC: “Mutually Parasitic” by Slow Gherkin begins

JAMES VO: They played a punchier form of ska music called 2-Tone , with this whole attitude of, “We gotta come together to stand up to the racists who are literally stalking us and attacking us. And we can’t let the powers that be pit us against each other.”

CATHY VO: Wait, so does “2-Tone” refer to… races?

JAMES VO: Yeah, it’s —

CATHY VO: Okay.

JAMES VO: — it’s Black and White.

JAMES VO: I know the cool Asian thing to say is, “It’s not Black and White, there are Asian people too.”

JAMES VO: But, you know, the 2-Tone iconography, the thing you probably recognize most, is black and white checkers.

CATHY VO: Ooooh yeah!

JAMES VO: That’s a forever ska thing, and it all came from that emblem, Black and White together, uh, racial solidarity…

CATHY VO: Got it.

JAMES VO: Yeah.

CATHY VO: And those 2-Tone bands, I know some of their music made it to the U.S. — but it never got onto the top 40 charts or anything like that.

JAMES VO: No, but ska was definitely spreading around the world. And during the 80s and 90s, a whole underground music scene cropped up in the States around ska .

JAMES VO: It was importing some of those 2-tone political ideals and mutating the music into all these different strands — ska-punk, ska-core, ska-funk, ska-jazz…

CATHY VO: Yeah! I remember, so that — that’s when you and I were exposed to the music. Right?

JAMES VO: Yeah, and this is where I’ll point out another reason that I think I’ve met so many Asian American ska fans.

JAMES VO: Aside from the fact that, you know, saxophone solos are just, like, the best thing in this world (laughs) — just listen to this!

MUSIC: “Mutually Parasitic” ends with an awesome saxophone solo

JAMES VO: OK, so I wanted to say is that ska music has this hands-on way of respecting and sharing cultural heritage.

JAMES VO: One time my friends and I went to see The Slackers — they're a band from New York .

JAMES VO: And instead of playing at, like a typical venue or a nightclub, they booked a community center (laughs) that… It’s a place that teaches international dance classes.

CATHY VO: Yep.

JAMES VO: And, so they do the show. But an hour before the show, they just sat down on the stage with all the lights on, and people huddled around the front of the stage.

JAMES VO: And they had a teach-in with us about where ska comes from. So they’re talking about the African, the Afro-Caribbean history of ska, the Jamaican immigrant history with ska, the political history of ska, like all of these… decades and decades, and it’s not like they’re reading from a book.

JAMES VO: Right? They’re, they’re kind of passing down things that they learned by going to find the music that is older, understand all of its roots…

CATHY VO: Cool! That’s like, they're kind of sharing a culture, and inviting you to be a part of it, with —

JAMES VO: Yeah! It's like…

JAMES VO: Here's a place where you can access the history that came before, and also add our own chapter to it —

JAMES VO: That, I think, is a really helpful experience, because…

JAMES VO: …as Asian Americans, I think we can feel pressure to be authentic, like to keep the traditions of our parents and grandparents.

JAMES VO: But then simultaneously we’re pressured to erase ourselves by assimilating, making White people feel comfortable, minimizing ourselves for, like, this idea of a melting pot…

JAMES VO: So, you know, in Asian American conversations, I think this typically comes up through the “two worlds” idea, right?

CATHY VO: Mmhm. So you have one foot in your Asian world, one foot in your American world.

JAMES VO: Yeah, but me personally, speaking as a second gen American — I’ve never felt like I live in two worlds… (laughs)

JAMES VO: I mean, I live in one world. And in this world, everyone is telling me to conform to their expectations, like, telling me who they think I’m supposed to be.

JAMES VO: That was my experience growing up, and it was the ska scene that told me:

JAMES VO: "Hey kid! If you are sick of conforming… if you're tired of following the rules of this rigid, binary world… then you know what? Just go find some people you can get along with, and, like, go make your own world."

CATHY VO: Nice.

JAMES VO: To me, that feels like a superpower.

JAMES VO: And I happened to pick up on that superpower from an Asian dude who dropped out of college to be in a ska band.

MIDROLL: Promo for “Spam: How the American Dream Got Canned”

Announcer VO: New on The Experiment — we’re opening a Pandora’s can. A Spam can of worms… to uncover the power of America’s favorite mystery meat.

Announcer VO: Spam has traveled around the world. It’s inspired poetry, and it’s set in motion a union battle that would change the course of history.

Announcer VO: “Spam: How the American Dream Got Canned” is a three-part series about food, work, and family, on The Experiment — from The Atlantic and WNYC Studios. Listen wherever you get podcasts.

Segment 2: Secret Asian Man

CATHY VO: This is Self Evident. I’m Cathy Erway.

CATHY VO: Our producer James was just sharing his experience of getting into ska music.

CATHY VO: And a big part of that experience was hearing a Korean American musician named Mike Park.

Segment 2: Secret Asian Man

MUSIC: “Sultan’s Cross” by Let’s Go Bowling

JAMES VO: Mike Park grew up in a suburb of San Jose, California.

JAMES VO: He was one of 6 Asian boys in his high school .

Mike: Somehow five of us were in the same P.E. Class.

Mike: And I was good at sports so I would always be a captain, and I would purposely only pick the Asian kids.

Mike: Cause we thought it was funny.

Mike: But also, ’cause we stuck together.

JAMES VO: Mike and his friends were also really into music, especially the stranger rock bands, and underground punk rock groups.

JAMES VO: But Mike found his true calling in 1985, at the local movie theater.

Mike: I saw a movie called Dance Craze, which was about the ska movement in England…

Mike: The energy. The footage of them playing live was amazing,

Mike: And it was the first and only time I've seen people dance during a movie. So people are just dancing in the aisles, and it was pretty awesome. And I danced too!

Mike: That was the start.

JAMES VO: Mike got deep into the 2-Tone bands he was dancing to at the theater — like The Specials, The Selecter, The Beat, The Bodysnatchers.

JAMES VO: And most of those bands were multiracial .

JAMES VO: Then, he went to a $3 show in a basement at Santa Clara University to see Fishbone — an American, all-Black band that showed him an entirely new world of music.

Mike: Organized chaos. Just frenetic ska, punk, jazz, funk… and just going ape shit wild. And everybody in the crowd going crazy, and just a sweaty dance floor of just people having a good time.

Mike: Especially, if it was like a school night, and I went and saw them, I couldn't sleep. And I would be, like, running on just a few hours sleep, going to school.

Mike: Up to that point, I had never experienced anything like it. And even today at 52 years old, I've never experienced anything like it.

Mike: But what really struck with me was the logo, the simple Fishbone logo with the "Fuck Racism" on the front of the shirt.

Mike: And that was powerful!

Mike: It just changed, changed my life really.

Mike: That was the reason I wanted to be in a band, 100%, which has led me down this path.

JAMES VO: After high school, Mike started a band called Skankin’ Pickle . The band mascot was a pickle dancing to ska music.

JAMES VO: Mike sang and played saxophone, and they self-released their first album, "Skafunkrastapunk," in 1991 .

JAMES VO: This was 5 years before ska bands would make it big on mainstream radio .

JAMES VO: If they were going to make it, they had to go on tour across the country.

JAMES VO: And Mike had to tell his parents he was dropping out of college to play in a band full time.

Mike: It was — was at least a semester where I just pretended to go to school.

Mike: They'd ask "How was school?"

Mike: I'm like, "Oh, it was great."

Mike: But eventually I just, I just had to man up and tell them, Hey, I'm going to go on tour and I, I'm not going to school. And it was tough.

Mike: It was tough for them because they just felt like it wasn't the right choice; it was tough for me because I was scared to tell them.

JAMES VO: I first found out about Mike Park in the 8th grade, when I was starting to feel totally alienated by popular music.

JAMES VO: It was the time of peak Spice Girls, and the start of the Boy Band era.

JAMES VO: To me, everyone in pop felt like highly produced figurines of young people, who couldn’t actually speak to anything I cared about in the real world.

JAMES VO: So just like Mike fell in love with ska when he saw the movie "Dance Craze," and felt that energy coming through the screen, I fell in love with ska when an older kid handed me a cassette copy of “Skankin’ Pickle Live.”

MUSIC: “David Duke is Running for President” ends

JAMES VO: At the time I had no idea who Mike Park was, but there was just nothing about this record not to fall in love with.

JAMES VO: The first track was a comedic parody of Saddam Hussein.

JAMES VO: The second track was called "Fakin' Jamaican," basically poking fun at people who appropriate Jamaican culture.

JAMES VO: The third track was called “David Duke Is Running 4 President" ; it was a completely straight-faced 90-seconds of Mike basically shouting at the audience, “Am I the only one who’s worried that a Ku Klux Klan leader is running for president?”...

Mike, singing: I think I’m in shock, think I’m gonna cry

Mike, singing: Cause millions of people, they really love this guy

Mike, singing: A Nazi, a Klansman is running for president

Mike, singing: David Duke is running for president!

JAMES VO: The entire thing was live. Aside from playing trombone in my middle school band, I'd never seen live music, never heard a live concert recording…

MUSIC: “David Duke is Running for President” ends

JAMES VO: And I'd definitely never heard the frontman of a rock band introduce a song like this:

Mike, onstage: This song is called “Pabu Boy.”

Mike, onstage: “Pabu” is a Korean word meaning “stupid,” and this is what my dad used to call me a child, when I would watch TV.

Mike, onstage: He’d go, “You Pabu Boy.”

Mike, onstage: I'd go, "Thanks dad." So this goes out to you, dad.

Mike, onstage: Pabu boy! THAT'S ME!

MUSIC: “Pabu Boy” by Skankin’ Pickle

JAMES VO: I started looking for every Skankin’ Pickle album I could find, started living completely in my headphones…

JAMES VO: My mom was not pleased.

JAMES VO: And (laughs) you know what? Mike Park's mom wasn't pleased either.

Mike: My mom cried almost every day...

Mike: I would bet a good chunk of money that she told me to go back to college every day that I physically saw her, when I wasn't on tour.

Mike: So, yeah! Not a lot of support.

Mike: It was only when I started making money that I got support.

JAMES VO: But even as Mike's band started making pretty good money, and building a huge following across the country, he started to feel the cost of all this non-stop hustling.

Mike: Yeah, I was burnt out on touring; I think we were playing like 200 shows a year from 92 to 96.

Mike: We were not in a tour bus. We were just in a van. And we were just staying on people's floors for a good chunk of our touring lives. So...

Mike: …it sucked!

MUSIC: "Pabu Boy" ends

SOUND: CD jewel case opens

SOUND: CD goes into disc tray, tray retracts into a stereo, and begins to spin

JAMES VO: When I got a hold of the newest Skankin' Pickle CD, I read a message from Mike Park in the liner notes, saying that he was leaving the band!

JAMES VO: This was right when ska bands were becoming a surprise hit, taking the rest of the country by storm. So Mike was quitting just as MTV was constantly playing a music video for the song “Sell Out” by the band Reel Big Fish , which was literally about cashing in on ska's 15 minutes of fame.

JAMES VO: But then I found out that Mike wasn't quitting on ska.

JAMES VO: He was doing the opposite — starting new bands and making new music that was explicitly from the perspective of Asian Americans embracing their identity and calling out racism, including anti-Asian racism.

JAMES VO: And to put out this new music, he was starting a whole new record label.

MUSIC: "Signature" by The Chinkees begins

Mike: An ethical business that can showcase bands that have no home. I think that's how every indie label starts.

Mike: And the reason why I called it Asian Man was I wanted people to know it was a person of color that was running this.

JAMES VO: The Asian Man Records logo was based on the South Korean flag.

JAMES VO: The office was literally Mike's parent's garage.

JAMES VO: He signed the bands that he’d made friends with, and the bands he’d inspired when he was on the road with Skankin’ Pickle.

Mike: And within a year, I think we grossed over a million dollars.

Mike: That's from a garage with me as the only employee.

Mike: And that's how it was; I could have put out anything that said "ska," and I was going to sell a ton of records.

MUSIC: "Signature" ends

Mike: And that's what was happening. Like Moon Records from New York, they started a subsidiary, a ska subsidiary of their own ska label called "Ska Satellite," so they could put out bands that sucked! And still make money off them.

JAMES VO: But what made Asian Man special wasn't the sales; it was how Mike made the sales.

JAMES VO: He’d produce albums with teenagers on shoestring budgets, and use his reputation as an OG ska musician to get their music into stores.

JAMES VO: He would sell thousands and thousands of CDs directly to fans from the garage , without middlemen, without marketing, so that people could actually afford to pay for the music.

JAMES VO: And when the Vans Warped Tour was laying the groundwork for corporate- sponsored music festivals , Mike put on a grassroots tour called "Ska Against Racism," which donated all of its proceeds to anti-racist organizations.

JAMES VO: Seeing all the Asian Man bands and fans come together for Ska Against Racism completely changed my perception of what music could be…

JAMES VO: …but the Mike Park story that sticks with me most is when I was in college, and Mike booked a show across town. And I didn't have a car. But one of my Korean classmates was actually going to play cello for a couple songs during his set.

JAMES VO: So I said, "Hellen, uh, how are you getting to the show?”

JAMES VO: And she said, "Ah, Mike will give us a ride." And… yeah, Mike came and picked us up… (laughs in disbelief)

JAMES VO: So to me, that’s Mike Park. He gave a fan he’d never met a ride to his own show.

JAMES VO: And when I talked to Asian Man Records fans from all over the country, even people who had never met Mike in person had these feelings of familiarity and trust.

JAMES VO: Like every new piece of music came with a little reminder that an Asian Man was at the wheel, trying to steer us in the right direction.

MUSIC: "Onyonghasayo” by Skankin’ Pickle begins

Eugene Yi: One of the first songs that I started singing to my daughter was Skankin' Pickle's "Onyonghasayo."

Steph Ching: (Laughs) Aw, haha, sorry, I don't mean to laugh. I think that's really cute.

EY: I mean, the lyrics of the song are literally, in Korean, "Hello? Hello? I can't speak Korean."

Skankin’ Pickle on "Onyonghasayo”: 아이고!

EY: And then on top of that, like, the sort of Korean knee-jerk expression of dismay, like "Ai-goh!"

EY: As, like, a ska chant?! Like, I mean, what the fuck?! It was crazy! I was like... I didn't realize that, like, music and art could combine so many aspects of my identity with it, too, in just kind of a fun package.

MUSIC: "Onyonghasayo” ends

Chris Erway: I just remember being so stunned, like, it's just telling you, "This is who I am."

MUSIC: "You Don’t Know" by The Chinkees begins

CE: You're allowed to talk about this? You can talk about your being Asian? You can talk about the feelings you have when you know, people assume things about you just because you're Asian?

Rahul Singh: Mike Park was up on stage, and I remember kind of having this feeling of like, "OK. It's all right for me to be here, it's all right for me to enjoy this music, and I should make sure that other people feel included as well."

Mitchell James Cho Barys: He had a, like a printout sheet, like, “How to start your own band or how to like start your own record label”...

Kate Page: Here's what it looks like when you're not getting screwed over, when someone's not just trying to exploit you...

KP: I feel like that's a hard trait to find these days. (chuckles)

JB Roe: As I grow older, and, you know, the Asian-American community becomes more and more highlighted by companies, then we can see that all that translates to is commodification, right? It's like, “How can we commodify a culture and sell it to other people?” Whether it be food, clothing, whatever.

JBR: Whereas, on the DIY end, with things like Asian Man, they're making this thing because it's something that they genuinely care about and believe in.

JAMES VO: So I’ve been playing all these clips of conversations I had with Asian Americans who love Asian Man Records. And it actually turns out that multiple people who helped start Self Evident were also influenced by Mike Park.

MUSIC: “You Don’t Know” ends

JAMES VO: Including our sound engineer, Tim.

Timothy Lou Ly: Like tons of other struggling teenagers who don't know what the fuck to do with their lives… I kind of went out seeking the answer.

TLL: And the answer for me at that time was I'm going to live a musician's life, whether that be playing in a band or owning a record label or something like that.

TLL: So I Googled local record label owners, and Asian Man Records came up.

TLL: And so I emailed Mike Park through the Asian Man website, and said, "Hey. I'm wondering if I could talk to you, man."

TLL: He messaged me back, saying, "Yeah! Come on down, come to the garage, and we'll get you on your way.

TLL: I was just thinking, “Yeah!” Like, he's going to say, "Follow your dreams of music , go out on the road, do this and that... like, leave your family” (laughs) literally, like…

TLL: My family to me at that time was an obstacle to the things that I wanted to do.

TLL: But he basically said, "I'm not going to tell you how to live your life."

TLL: "I can't tell you to leave your family, to ditch your family. Like that's totally the wrong move to do. What are you thinking?" (laughs)

TLL: Because he straight up said, "Yeah, this is my mom's house. I do all my business outta here."

TLL: Things for me could have gone a completely opposite and wrong way. And had he not been real enough to tell me that... oh man, I would be in a completely different place. I'd have been so much worse off.

JAMES VO: So Tim stayed at home, finished school. Kept playing music. But he also grew up.

JAMES VO: He’s still close with his family, and he still lives just a short drive away from Asian Man Records.

Segment 3: Asian Man, Singular

JAMES VO: It’s the same with Mike Park. When Asian Man started bringing in good money, he bought a house not too far from his parents’ house.

JAMES VO: The entire business still fits into their two-car garage and basement in Monte Sereno, CA.

Mike: So this was here when we first started.

James: What is this?

Mike: Phone line (chuckles), dial-up phone line. So this is the original phone line right here.

Mike: I just ran the phone line through the downstairs, uh, phone jack and brought it into the garage, and kind of did everything here, and…

Mike: …every square inch of this downstairs was used to pack, or actually hold records or extra jackets and CDs and stuff like that.

JAMES VO: Over the past two years, Mike's thrown out over 50,000 records and CDs .

JAMES VO: But he still has dozens of photos pinned to bulletin boards — of bands, of random fans, of family members — going back to the 90s.

Mike: Looking at these pictures definitely brings back memories.

Mike: That’s my dad when he was alive. He passed away 20 years ago, so, shows you how old that, that is.

Mike: I can recall him pulling the car into this garage and working on his car, doing everything himself.

JAMES VO: Mike’s mom is 85. And since the label’s been financially stable for over two decades, and Mike and his wife have been raising their own kids, it’s been a while since she told him to go back to school.

JAMES VO: But she does make lunch for him, just like when he started 25 years ago.

JAMES VO: Most days, Mike runs Asian Man Records all by himself. His TikTok account has videos of him reading unreasonable emails he gets from the rare customer who doesn't realize that customer service is him.

Mike on the AMR TikTok: We are not Amazon! And it's not even “we.”

Mike on the AMR TikTok: It's “I.” As in, “I'm the only guy who works here.”

Mike on the AMR TikTok: It's not Asian Man Records Prime. It's just Asian Man, singular.

JAMES VO: He's still writing and releasing new songs of his own. He still puts out a few new records a year by musicians less than half his age .

JAMES VO: He even posts videos of himself listening to demos from unsigned bands.

Mike on the AMR TikTok: First listen. Awesome. I could see this band just playing like a DIY punk show. Everybody pushed up front singing along to the singer…

JAMES VO: But Mike doesn't go on tour anymore. No matter how often his longtime fans around the country beg him to get back out there and help us relive our ska dreams.

Mike: Mostly it's just commenting on social media, or it's straight up emails.

Mike: And they'll say, “We need you, we need you to do these again to help this next generation,” but…

Mike: I think it's them looking back to their youth and when they went to Ska Against Racism and how much it affected them... now, as adults.

JAMES VO: When I first heard Mike's voice on a bootleg cassette, the ska show felt like the best place for an Asian kid who wanted to take on the world. Make it into something different.

JAMES VO: But that was twenty-five years ago. Today, it feels like America’s even more committed to the status quo. Like anti-Asian racism is more brutal, more cruel.

JAMES VO: And when Mike and I talked, the idea that ska could be a tool in the struggle against racism and injustice felt more like a dream than reality.

James: Mike, I was wondering how this most recent wave of anti-Asian violence has affected you.

Mike: It's terrible. I feel empty inside and I've used music as, as therapy.

Mike: All the music I've written over the last two years, and I've written a shitload of music... it's angry music. Like, I'm angry.

Mike: Asian people are always seen as the… “The good minority. They're not troublemakers.”

Mike: Are we deemed that mouse like or timid, that anybody can fuck with us? Fuck with our elders?

Mike: Continue to blindly attack innocent bystanders?

Mike: It, it’ll continue to make me angry until there's some movement in the right direction. I don't think we're going in the right direction. I don't think you think we're going in the right direction.

Mike: It's like one step forward, two steps back. In my lifetime. That's how it's feeling right now.

James: Yeah, I was actually about to ask if it’s shaken your faith.

James: You’ve been making anti-racist music from an Asian perspective for over three decades. It’s been 24 years since you led the Ska Against Racism tour, and things today seem so dire, so…

James: At this point, what do you think the power of your music is?

Mike: It's hard to tell. I know it affects a lot of people in a positive way, just through decades now of feedback.

Mike: It helps people to cope with their insecurities, their anger issues... It's able to perhaps sway someone who doesn't understand what I'm going through, or what the Asian American community is going through.

James: I know I’m not the first person to say this, but when I found out about Ska Against Racism, the entire thing blew my mind. Just seeing a musical movement that was recognizing and pushing back on racism, in the year 1998, like, that was nowhere on anyone’s radar where I grew up. And you raised, I believe it was, $23,000 —

Mike: Which is p —

James: — for anti-racist organizations.

Mike: Yeah, which is pennies. Pennies! PENNIES!

James: (chuckles), OK, but when you say pennies and laugh... I mean, for a fan like me, what's the story of that tour that I never saw?

Mike: I mean, the shows were great. People were great. It was, it was amazing.

Mike: Historically ska was a very political, like, working class music and it had turned into kind of this, like, comedic, circus music, and the politics were lost, and so I just said, okay, let's do something that's more than just strictly capitalism.

Mike: So that's how it started, but the reality is anytime you try to put together some kind of benefit tour, it's tough.

Mike: If we had planned it better, I could have been more involved with each city, and had the right people out, the right speakers. We just didn't, we didn't have enough. We didn't have enough activism.

Mike: I was making no money, I was donating my time 100%.

Mike: I just felt like, you know, "Why? Why am I even doing this?"

Mike: And then I'd have to step back and go, "Well, the reason you're doing this is because you do want to make a difference. You don't want to just put another faceless rock tour together. You want to have a message behind it.”

James: And since you’ve had such a tough time with these more ambitious projects, like the benefit tours, or your non-profit community center, which basically required a ton of unpaid work for five years…

James: Like, what’s your perspective on the personal sacrifices that it takes to do this stuff?

James: Like, have you changed your mind about how much people should be pushing themselves, sacrificing their well-being, to a degree, for the cause, for the community?

Mike: My thought process has flipped 180 degrees over the last couple of years, and that's because I had a complete mental health breakdown.

Mike: At the end of 2019, I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder. I had always been a high stress, anxious person, but I've always been able to function at a high level, but that year at the end of that year, I… it just wasn't working anymore. I couldn't, I couldn't function. I had to, I had to go on meds.

Mike: My best friend who's a doctor at Kaiser was able to get me, like, instantly get me Xanax .

Mike: He's like, "Dude, you need something right now to help," and I was like, "Oooh, this is great." So I totally understand Xanax abusers. (laughs)

James: (laughs)

James: How did you get to that conversation being to the point where someone could visibly or audibly say you need this right now? Like what was happening?

Mike: Oh, I was like in a ball, like I couldn't get out of bed and that's so unlike me, I've just like...

Mike: My heart was beating so fast all the time and it was just like…

Mike: Basically if someone said, let's go to an insane asylum right now, I would have said, "Okay, let's go." It was that bad.

Mike: Being a father, being a husband, being a son. Having to be so close to my mom because my business was there. Having to worry about all my mom's finances, her bills, my family's finances and bills, the bands on Asian Man...

Mike: it was to the point where my brain couldn't shut off.

Mike: And that was from overworking.

Mike: So when I was going through that mental health spiral, I tried everything.

Mike: I did meditation, I took meds, I did therapy, sauna, yoga, acupuncture.

Mike: Constantly researching, Googling, which is a terrible thing to do, but I found a comfort zone of what worked for me.

Mike: The meds helped. It took a long time, took like a good three months for that stuff to kick in. Lexapro, shout out to Lexapro.

Mike: And I finally started seeing, like, “Oh, okay, I see some light at the end of the tunnel.” And then slowly, like, made healthy decisions.

Mike: Just getting outside. Walking in the morning every day, at least 45 minutes before I even started my day.

Mike: Looking at my surroundings and taking a second to breathe, pick a spot, and just meditate for a little bit.

Mike: So I worked hard to get healthy, and continue to work hard.

James: So going back to this work ethic thing, right?

James: Like working too much, burning yourself out...

Mike: Yeah.

James: It's, this is, the interesting part of it, it's like...

James: We need a community. Right?

Mike: Yeah.

James: It's all about building and connecting with that community that we know is there, can be there, and helping each other.

James: But ironically, to do that, you have to go out on your own and then you gotta do very difficult things. And it can be at your own expense and sometimes you have to be like, "I got to stop, because I'm going crazy, or I'm burning out."

Mike: I burned out. I stopped touring. I couldn't do it anymore.

Mike: But that's DIY! Because it's people who are waiting for someone else to help them, who are the ones who never get out and do stuff.

Mike: I, I think that's really the key, is you just gotta, we just need someone out there; some kids need to start a band that just influences the next generation.

Mike: Cause it ain't gonna be me!

MUSIC: “Still Down For Tomorrow” by the Bruce Lee Band begins

Mike: It's not up to us to decide what the next generation does. It's up to them. We don't know what the next counterculture movement is going to be.

Mike: As long as those artists are creating something unique onto themselves that gives inspiration to others, That's really all we can ask for.

Mike, singing: Guided by your voice

Mike, singing: Trailing me in song

Mike, singing: I’m still down for tomorrow

Mike: And that's just part of my job, and it's fun.

Mike: It's fun to like, learn about new things, new bands, new artists, new sayings, new techniques...

James: New sayings such as...

Mike: Just, you know, what kids they're little slang. "BRUH." (laughs)

Mike: Or just, whatever!

James: (laughs)

Mike: You know, I'm constantly using the word "BRUH" to my daughter, ’cause she says it so much to me.

Segment 4: Say Goodbye to Yesterday

MUSIC: “Still Down For Tomorrow” fades out

JAMES VO: When I went to the SKA DREAM show, I could see that plenty of people are still doing it for the culture. And there are plenty of younger bands that older generations of ska fans just aren’t looking for.

JAMES VO: But these generations are all connected. Jeff Rosenstock, the headliner, used to put out music on Asian Man Records with his band, Bomb the Music Industry.

JAMES VO: And the opening act was Jer Hunter.

SOUND: Jer speaks to the audience at the Ska Dream Nights concert

Jer: This is first Jer — the second Jer show, ever.

Fans: (cheer)

JAMES VO: They’re a 26-year-old, Black, queer musician from South Florida who’s probably best known for creating hundreds of ska cover songs on their Youtube Channel, Skatune Network .

SOUND: The muffled sound of Jeff Rosenstock playing “p i c k i t u p” at the Ska Dream Nights concert , while Jer dances on stage as part of the band

JAMES VO: After finishing their set, they basically just stayed on stage with a trombone and kept on playing with every other band. Just, like, dancing all over the place, and wearing a Fishbone t-shirt.

JAMES VO: Their name pops up in lots of stories claiming that ska is making a comeback after disappearing from the American mainstream.

JAMES VO: But Jer’s always the first to say that ska never went away, and that the ska scene has never been perfect. Including when it comes to racism.

JAMES VO: But the music has grown all over the world, and here in the U.S, the scene has gotten closer to its roots .

Jer: You had a lot of talented people who were making ska music, but like they were too ashamed of it because X, Y, and Z. And so they just like left the genre.

Jer: And so I feel like it weeded out all of the, like… the weak people, you know?

James: (laughs)

Jer: The people who like can't form their own opinions, the people who, who would otherwise gatekeep, were too cool to gatekeep ska, who want to exploit and only want to make money — it, like, weeded them out, and like, what you were left with was just, like, this, like, very small, but caring community of people.

JAMES VO: In 2020, when going to a ska show seemed next to impossible, Jer was one of 28 bands with a song on the new “Ska Against Racism” .

JAMES VO: Which was a multi-generational compilation made by Mike Sosinski, the owner of Bad Time Records ; a social media group called Ska Punk Daily — and of course, Mike Park.

JAMES VO: While the original Ska Against Racism tour lasted for two months and donated $23,000 in proceeds, the new Ska Against Racism made over $50,000 in one day , eventually grossing over a hundred thousand — and donating 100% of it to anti-racist groups .

James: How much do you know about the original Ska Against Racism tour?

Jer: I was probably, I don't even know if I was, wh — what, what year did that tour even happen in?

James: 1998.

Jer: I was three years old, yeah, so like, I was, I wasn't really able to go to a show and, and really be conscious about what was around in my surroundings at that point.

Jer: But I remember like having stickers in like very early high school that said Ska Against Racism, that I got at shows or whatever, I would see the shirts.

Jer: And it has a legacy; it kept inspiring other people.

Jer: And I feel like when you see that, especially as a person of color, you see that, okay, this is like a community that, that kind of wants to at least for overt racism, address it and make sure that's not a thing that's happening. And that's like a very comforting, because there's a lot of places where, you know, that stuff does happen and people kind of don't care.

James: Something I talked to Mike about was just, he always felt frustrated by that experience.

Jer: Right.

James: And didn't feel like he was making enough of an impact. It definitely took a lot out of him personally.

Jer: Mmhm.

James: It's just this torn feeling, I think, of trying to do something positive and in the right way, but… coming up against criticism, weirdly for not doing enough?

Jer: Yeaah.

James: And then also, criticism for trying in the first place…

James: How does it feel for you to hear that that's the reality of what the original Ska Against Racism did, and how it went down?

Jer: As an activist and as, like, a leftist type of perspective, you really want all of the issues to be solved. And like, we all want to like, kind of like make this impact to, like, change things, because like, it feels like we have no control over like a crumbling world, but…

Jer: We don't need, like, one person making the huge change. We kinda need everybody making a small change.

Jer: So, like, did, did Mike solve racism in music? No.

Jer: But also, like, Mike probably inspired hundreds, if not thousands of people over the time to kinda start to question racism, think about it a little bit deeper, and inadvertently, if that never happened, the 2020 compilation Ska Against Racism also would have never happened, which raised nearly a hundred thousand dollars for organizations, you know, like…

Jer: Because of the money raised through that, you have like a young black girl who's learning how to code. And that's a very useful skill to have, especially in the world that we're going into. So like someone who might've not had an economic opportunity has been given an economic opportunity.

Jer: You have someone who might have otherwise been facing jail time, and now they're not because of the money that was donated towards the NAACP legal defense fund.

Jer: Addressing racism in the nineties was like, "Let's not be racist. We're past that.”

Jer: Now the addressal of racism is like, "Racism is a system that is embedded within our society and how do we actively dismantle that system and recognize, like, what upholds that system?"

Jer: That's something that the new Ska Against Racism compilation does a better job at doing, at least with like the bands active.

Jer: A lot of these new bands had been donating to like local mutual aid groups, like groups that fight for prisoner's rights and stuff like that.

Jer: Offering mutual aid that, like, watches your kids while you go do like the voting, you know, watches your kids while you go do your job, so you can like build much more of a base for you to be stable and to get out of these conditions. Like…

Jer: To me that's very, very important, where someone's life very literally, materially being made with, because of what we have been able to do.

JAMES VO: Like most ska bands today, Jer can’t live entirely off of this music.

JAMES VO: They work as a marching band teacher , and compose music on commission from cartoons and games and brands.

JAMES VO: They’re just starting to earn royalties and go on more live tours.

JAMES VO: And their most steady source of income is paid subscriptions to Skatune Network.

JAMES VO: It’s video channel where Jer does ska covers of songs, ranging from Childish Gambino’s “Redbone” to my personal favorite, the Koopa Troopa Beach Theme from Mario Kart 64.

Jer: The stability honestly comes from the Patreon for Skatune Network. That's where like… "Ahhhh, I don't have to worry about my rent."

James: And with Skatune Network on YouTube, you're doing covers.

James: And a lot of times they're covers of very well-known songs.

Jer: Yeah, oh yeah.

James: Yeah. Do you ever feel like what you do on YouTube is in a way responding to the nostalgia craving? Is there some extent to which you yourself are a little trapped by these forces of huge demand for, "Give the people what they want and give the people what they know?"

Jer: Yes! Oh, oh, yes!

Jer: I did a Blink 182 cover.

Jer: I did three actually, but two of them really popped off. And as, as successful as they were, and as they gained me like a hundred thousand or so subscribers…

Jer: In a way, it was also kind of a mistake because now what I'm stuck with is a hundred thousand or so people who, like, won't watch my videos unless I do like a pop punk cover, you know, like they, they only want what they're nostalgic for.

Jer: Which sucks, because I feel like whenever I do a cover, I'm creating something new, and like, I'm a type of person where if I don't know a cover, I'll still watch it because I like that artist.

Jer: If I hear a cover and I don't know, it's a cover, then it's an original to me. If I do know it's a cover, but I don't know the song, it stands on its own.

Jer: And for some people, I think that they just like, because of nostalgia, they can't see things as standing on its own.

James: One of my biggest running questions throughout this whole process of talking to ska fans has been how much of what we love about this music is truly unique about the music and how much of it is just us rehashing our formative memories.

James: I'm 38, you're 26. Mike is 52.

Jer: Right.

James: And you're a working musician.

Jer: Right

James: And then you go into the shows and you go online.

James: And you're constantly interacting with, and sometimes butting up against my generation.

James: Or Mike's generation talking about their ska, or not always living in the present, sometimes living in the past. How does that come across to you?

Jer: I think a lot of people miss a certain period of their life for one reason or another, and then another part of it is there's actually like a scientific reason behind nostalgia; nostalgia is created because when you're going through that period of puberty of your life, your brain is associating that with this, this rush of dopamine.

Jer: The first time you hear that record, when you're 14 years old, you're like the first time you watch this show and it has a special place in your heart...

Jer: It's not in your heart. It's literally in your brain. It's like what your brain remembers that dopamine like, like dopamine to be.

Jer: So I think a lot of people just get really attached and they allow that like sense of nostalgia to really cloud like their, their vision, and that's like a thing that always strikes me about the language.

Jer: When people talk about, like older ska, like nineties scholar, like whatever.

Jer: They always kind of word things as if it's a competition.

Jer: And music's not a competition when I'm listening to one band, I'm not like, "Oh yeah, this is good, but it's, it doesn't compare to this."

Jer: Like, to me, that's so weird to talk about music like that. Like something that's like an art that's so like subjective, to treat it like it's objective.

Jer: They make their nostalgic to an objective, like, take, where, "If I'm nostalgic for it, it's objectively better."

Jer: And I'm like, "Naw, that's not true. Like, that's not true at all," like...

James: (laughs)

Jer: It's longing for a time that's not going to come back. And I'd much rather focus on building a type of future. I want to see rather than longing for a past, that doesn't exist anymore.

Jer: That might be a little deep and philosophical and when the question asked is "ska nostalgia," but I think it just translates to any facet of life.

Jer: Like I could get hung up on the nostalgia of a song or a band or as type of music, or I can take that same energy and try to find something new and fresh I've never experienced before. I think that's the best thing about being a human and being alive is all of the experiences in art and people and culture that you can have.

Jer: And nostalgia, in my opinion, just gets in the way of that.

SOUND: The muffled sound of Jeff Rosenstock playing “p i c k i t u p” at the Ska Dream Nights concert , while Jer dances on stage as part of the band

James: So by the way, I was at SKA DREAM night in Brooklyn, which was just amazing, and I wanted to ask you, what was the best part of playing that show?

Jer: Jeff fans are awesome. Like, they're really incredible people…

Jer: There's a lot of like, uh, representation, especially queer representation, which is something that I feel like there is not as much of in ska —

Jer: And so to see kind of like a lot of like people who are like, you know, me as like a queer person, to be in a show where the audience is like that, where the people in playing it with both in my band and in Jeff's band are all like-minded and, and very, like, it just felt safe and comforting.

James: It really punches through all of the things that I feel kind of push down our humanity.

Jer: Mmhmm.

James: And… It's so simple!

Jer: Yeah. So there was actually a very specific moment.

Jer: It was just like a moment in a song where...

Jer: I'm just dancing. And Jeff's dancing. And then we just like, look at each other and then we just start dancing together. Like, that's it. That's, it’s, that's the whole moment.

SOUND: Jeff Rosenstock leads the audience in a triumphant chant:

Band and fans: SKA! DREAM!

Band and fans: SKA! DREAM!

Band and fans: SKA! DREAM!

Band and fans: SKA! DREAM!

Band and fans: SKA! DREAM!

Band and fans: SKA! DREAM!

Band and fans: SKADREAMSKADREAMSKADREAMSKADREAMSKADREAM

SOUND: Cheering fans fade under Cathy and James

CATHY VO: So James, after talking to all these people… do you still believe in the ska dream?

JAMES VO: Cathy. In the year 2022, if you ask me to choose between ska dream, and the American dream?

CATHY VO: (chuckles)

JAMES VO: SKA DREAM.

JAMES VO: Ska Dream, all the way. (laughs)

CATHY VO: Yep.

JAMES VO: But, you know, this whole time in the back of my head I’ve been asking myself, “What’s driving me to talk to all these people?”

JAMES VO: When I was just calling up my Asian American ska friends, a big part of it was reminiscing about the past.

JAMES VO: But when I spoke to Mike and Jer and got to know what it’s taken for them to keep this subculture going over the past two generations — I did start to feel like, now more than ever, ska has something real to show us.

JAMES VO: And it’s not about bringing back something from the past. It’s not about any kind of art form being magical enough to heal the world on its own.

JAMES VO: It’s about never forgetting that we ourselves have power.

JAMES VO: And no matter how oppressive and brutal the world can feel, we can still use that power, to find each other, to help each other, to make something just for us.

JAMES VO: So to wrap up this story, I wrote a song.

JAMES VO: I started sharing it with some of the ska fans I talked to for this episode, and asked if they wanted to play on it.

James: (grabs guitar again) Okay, let’s see if I can do this…

MUSIC: “No Guarantee” by James Boo feat. Dorian Love and Chris Erway

JAMES VO: OK, so, whether today is the first time you've ever heard of ska music, or you're already a fan, or you’re just feeling pushed down by the world right now…

JAMES VO: I hope this gives you a reason to move.

James, singing: I don’t know if another unity song

James, singing: Is gonna help us break down what’s gone so wrong

James, singing: Can’t see to Heaven on the stairway

James, singing: Can’t run from Hell on the subway

James, singing: Can’t hold a candle to

James, singing: the pretense of defense, of steps that go beyond

James, singing: Everybody wants you to take a stand

James, singing: When you wake up with the words taken out of your hand

James, singing: and go to work, without caring how

James, singing: the train tracks will stare at you now

James, singing: Step back, but don’t turn back

James, singing: We still gotta make a sound

James, singing: But I don’t need to know where I belong

James, singing: I don’t need the world to hear this song

James, singing: I just hope you’ll show me how you get along

James, singing: So that you and I can

James, singing: Buy staying free, with no guarantee

MUSIC: “No Guarantee” ends

MUSIC: “Stash” by Slow Gherkin begins

Credits

CATHY VO: This episode was produced, written, and sound designed by James Boo.

JAMES VO: With story edits from Julia Shu and Cathy Erway, fact checking by Tiffany Bui and Harsha Nahata, and sound mix by Timothy Lou Ly. Our theme music is by Dorian Love.

CATHY VO: If you liked today’s episode, write us a good review on Apple Podcasts, and share it with a friend!

JAMES VO: Yeah, it really helps people find the show!

CATHY VO: Almost all the music you heard in this episode is from Asian Man Records, thanks to Mike Park. You can see a full tracklist in the show notes and on our website, self evident show dot com.

JAMES VO: The original song we produced for this episode was written by me. It features Dorian Love on bass and Chris Erway on trombone and trumpet.

CATHY VO: Thanks to Mike Park and Jer Hunter for being on the show today.

JAMES VO: And HUGE thanks to all of the ska fans and Asian Man Records fans who spoke with me for this episode. That’s Arvin Temkar, Brad Baebler, Brian Kim, Chris Erway, Daisy Buranasombhop, Darryl Stein, Dorian Love, Eugene Yi, Holly Chan, JB Roe, Kate Page, Mitchell James Cho Barys, Rahul Singh, Raman Sehgal, Ravi Vasudevan, Sam Aqua, and Steph Ching.

CATHY VO: Self Evident is a Studiotobe production. Our Executive Producer is Ken Ikeda.

JAMES VO: This episode was made with support from PRX and the Google Podcast Creator Program…

CATHY VO: …and of course, our listener community.

CATHY VO: This is the last episode of our third season!

CATHY VO: If you want to help make our work sustainable, go to self evident show dot com slash supporters, and become a monthly sustaining member.

JAMES VO: Or you can sign up for our mailing list!

CATHY VO: I’m Cathy Erway. Let’s talk soon.

JAMES VO: Until then…

Mike: Fuck racism.